Connectivity and personalized experiences are a driving force in today’s digital era. Musicians, bands, and singers have a unique opportunity to capitalize on this by creating a music app that deepens their relationship with fans.

Imagine an app that does much more than just stream music—it becomes a vibrant community hub where fans can connect, discover exclusive content, purchase merchandise, buy concert tickets, and enjoy enhanced event experiences.

All of this can be accessed at their fingertips 24/7/365.

This vision isn’t just a dream or possibility—it’s within reach for any musician.

Whether you’re just starting out in the music industry or you have an established following, this in-depth guide will explain how to create a music app that elevates the fan experience and opens new avenues for revenue.

If you’re looking to innovate and connect with your audience on a deeper level, creating your own music streaming app could be the game-changer that sets you apart in the music industry.

Market Analysis and Conceptualization

There’s big money to be made with music apps—and music lovers are willing to pay top dollar to access their favorite tracks.

Research shows that the global music streaming market is expected to reach $125.7 billion by 2032, and it currently sits around $41.5 billion.

With music streaming services still growing at a 15.1% CAGR, there are fistfuls of money to be made—even if you can capture just a fraction of a percentage of this market share.

To be clear, we’re not trying to compete with the popular music streaming apps that are dominating this space. If you try to make a music app like Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube Music, or Pandora, you’ll likely have a hard time contending with those giants.

However, these platforms leave a gap for personalized, artist-centric experiences. This is where your app enters the picture as a niche service that offers something they cannot—an elevated, intimate connection between artists and their fans.

To carve out your piece of the music streaming industry, start by analyzing the needs and preferences of your target audience.

Fans of music, especially those following specific bands or artists, are often looking for more than just streaming. They crave behind-the-scenes content, direct interactions with their favorite musicians, exclusive merchandise, early ticket sales, and improved event experiences.

Your app can cater to these desires by offering unique features such as fan forums, VIP access to special content, in-app merchandise stores, ticketing services, and immersive event features.

Create a unique selling proposition (USP) that focuses on the specific benefits your app offers to fans and artists alike, such as fostering a community, enhancing fan engagement, and providing new revenue streams for artists.

Conceptualizing your app involves identifying these key differentiators. Ask yourself:

- What can my app offer that existing services do not?

- How can it enhance the fan experience in a way that builds loyalty and engagement?

- What unique revenue opportunities can it create for artists?

By focusing on these questions, you can begin to outline the features and services that will make your music app stand out.

Licensing and Legal Considerations

Creating a music app that streams content, sells merchandise, and offers tickets to events involves navigating a complex landscape of legal requirements and licensing agreements. This step is crucial not only to ensure the legality of your app but also to respect the rights of any other artists and creators whose content you wish to feature.

Here’s a breakdown of the process and tips on how you can navigate these waters effectively.

Music Licensing

The first step in legally streaming music through your app involves obtaining the necessary licenses from music rights holders.

There are generally two types of rights you need to be aware of—sound recording rights, controlled by record labels through organizations like the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), and publishing rights, which involve the composition and lyrics, controlled by publishers or songwriter collectives such as ASCAP, BMI, or SESAC in the United States.

To legally stream music, you’ll need to secure two main licenses:

- Mechanical Licenses: For the reproduction and distribution of musical compositions.

- Public Performance Licenses: For playing songs and music tracks publicly, which includes streaming over the internet.

Merchandise and Ticket Sales

Selling merchandise and tickets directly through your app introduces another layer of legal considerations. For merchandise, if you plan to use the artists’ names, likenesses, or other copyrighted material, you’ll need to negotiate rights and licensing agreements with the artists or their representatives. This ensures that artists are fairly compensated for the use of their brand.

Ticket sales through your app will require partnerships with event organizers or ticketing platforms. It’s essential to establish clear terms regarding the distribution of tickets, handling of customer data, and revenue sharing.

Legal Tips

- Consult with Legal Experts: Given the complexity of music rights and copyright law, consulting with legal professionals who specialize in entertainment law is invaluable. They can guide you through the licensing process, help negotiate agreements, and ensure compliance with all legal requirements.

- Transparent Agreements: Ensure all licensing and partnership agreements are clear and transparent, detailing rights, responsibilities, and revenue sharing. This helps avoid disputes and ensures a fair relationship between all parties involved.

- Stay Updated on Laws and Regulations: Copyright and music licensing laws are subject to change. Staying informed about current laws and industry standards is crucial to maintaining the legality of your app.

This step, while challenging, is a critical investment in the sustainability of a successful music app.

Technical Development

The technical development of your music app is where your conceptual ideas transform into a tangible product. This phase involves choosing the right technologies, developing the app’s architecture, and implementing features that will distinguish your app in the market.

Here are some key features to consider and the benefits they offer to users:

- High-Quality Audio Streaming: Essential for any music app, offering users the best listening experience with minimal buffering.

- Offline Playback: Allows users to download songs to their music library and listen to them without an internet connection, enhancing accessibility.

- Personalized Playlists and Recommendations: Uses algorithms to suggest songs, artists, and playlists based on users’ listening habits, offering a tailored experience.

- Artist Profiles: Where artists can share their music, upcoming events, and exclusive content, helping fans stay connected.

- Social Sharing and Interaction: Features that enable users to share songs, playlists, and concert experiences on social media and within the app, fostering a sense of community.

- Live Streaming: Allows artists to stream live performances or behind-the-scenes content directly to fans, creating intimate, real-time engagement.

- In-App Store: A platform for artists to sell merchandise and for fans to purchase it easily, supporting artists financially while offering fans a way to show their support.

- Integrated Ticket Sales: Simplifies the process of buying tickets for concerts and events, with options for notifications about upcoming events and exclusive pre-sales for app users.

- Customizable User Interface: Lets users personalize their app experience, from theme colors to layout preferences within the music streaming service.

- Interactive Features: Such as lyric displays, music videos, and artist interviews, enriching the listening experience.

- Feedback and Support Systems: To gather user feedback and provide assistance, ensuring continuous improvement and user satisfaction.

Don’t overwhelm yourself with too many features and try to build everything at once.

Instead, start with the features you need for your app to work—ideally aligned with the USP that you’ve identified earlier. Start there, and you can always add more down the road.

UX/UI Design

By investing in a thoughtful UX/UI design process, you can create an app that not only looks appealing but also provides a user-friendly platform that encourages longer engagement and fosters loyalty among its users

Create a design that prioritizes simplicity and intuitiveness to help users easily find their way around the app, with a minimalist approach to reduce cognitive load and enhance satisfaction.

Personalization also plays a key role in the design process, allowing users to customize the app’s appearance and functionality to their liking, which fosters a sense of ownership and engagement. The design should adapt gracefully across different devices, ensuring a consistent experience whether on a phone, tablet, or desktop.

Some app designers may consider using interactive elements to enhance the design. Things like album covers or music visualizers add an additional layer to the listening experience.

Adding lyrics or artist bios can also help enrich the content.

Accessibility is another important consideration, with features designed to accommodate all users, including those with disabilities, ensuring that the app is inclusive and available to a wide audience. Implementing multilingual support broadens the app’s appeal across different regions and cultures.

Visual branding should be consistent with the use of colors, fonts, and imagery that reflect the app’s identity, contributing to its recognizability and the user’s connection to the brand.

High-quality imagery and icons are essential for a professional and polished appearance.

Simply stated, you can’t rush through the design process. This will ultimately determine the look and feel of your app, which is crucial to retaining your users.

App Development and Testing

This stage involves translating your design concepts into a fully functional app—requiring a blend of technical expertise, creativity, and strategic planning.

Music streaming app development encompasses a wide array of tasks, from coding and integrating APIs to setting up servers and ensuring your app’s compatibility across various devices and operating systems. It’s a complex process that demands attention to detail to ensure that every feature works as intended, providing users with a smooth, glitch-free experience.

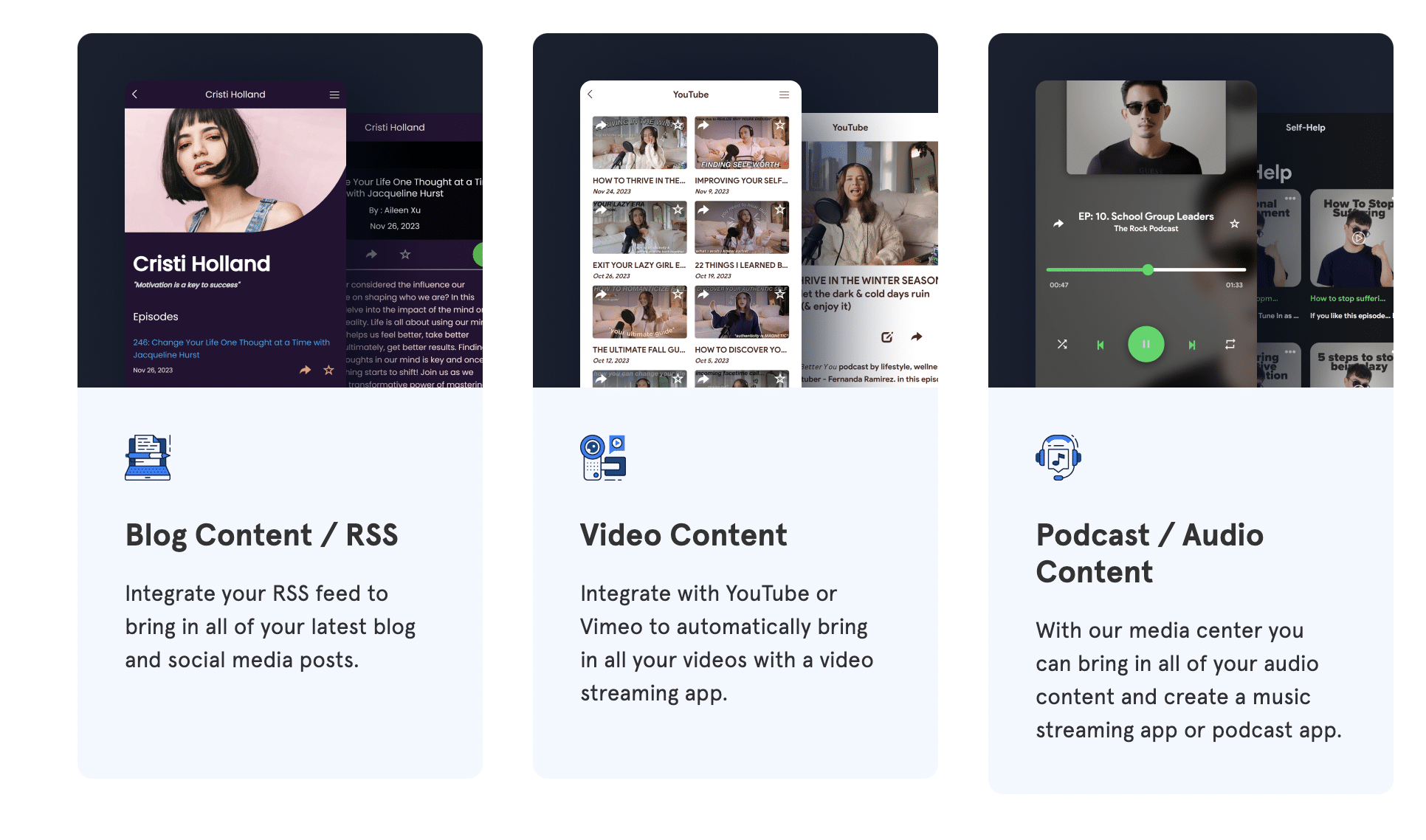

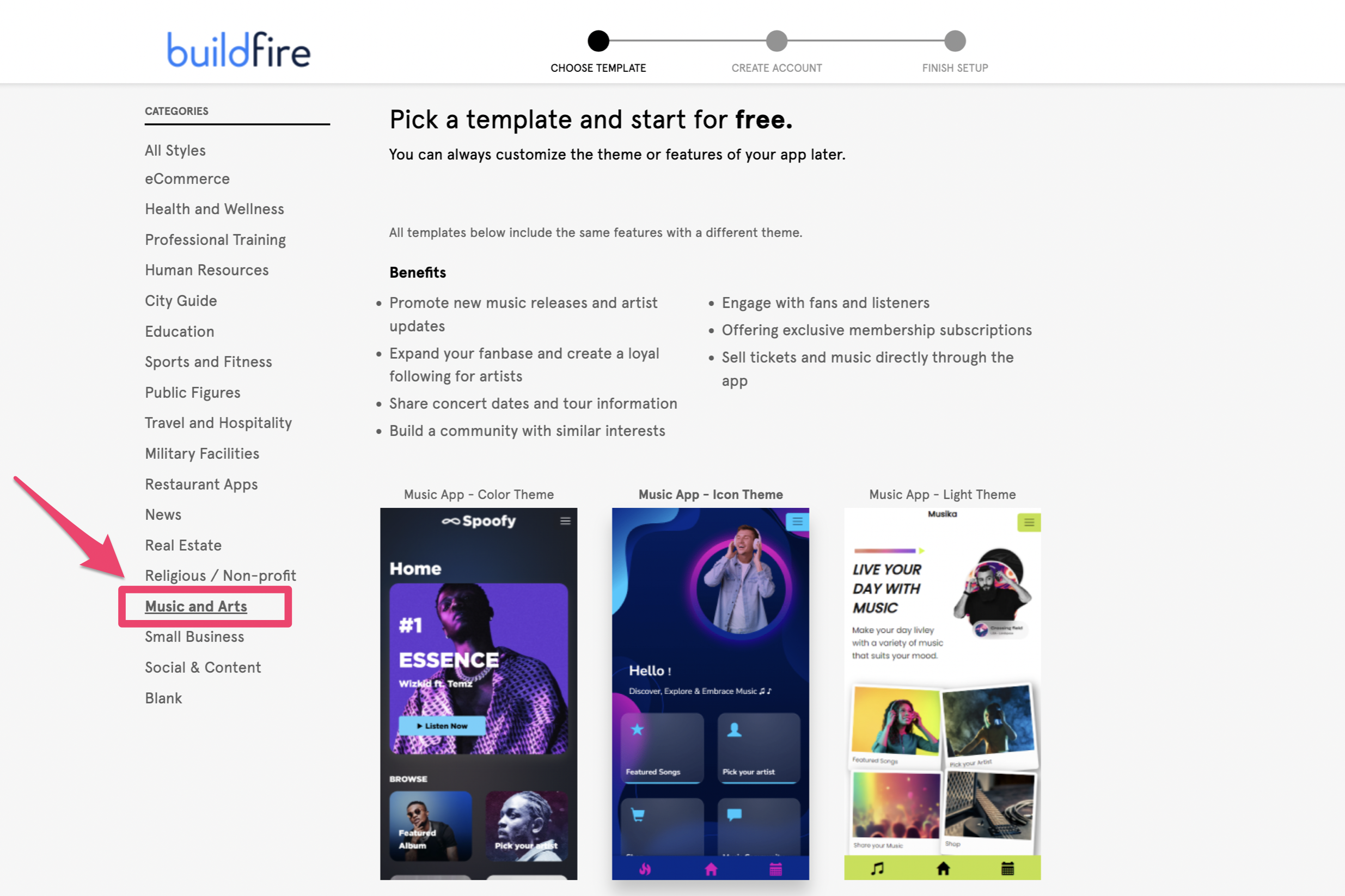

For those looking to simplify the app development process, platforms like BuildFire offer a powerful solution. BuildFire is designed to streamline the creation of mobile apps, providing a user-friendly interface that allows for the customization of features without needing deep technical knowledge.

With a wide range of plugins and templates, BuildFire can help bring your music app from concept to reality, facilitating the integration of streaming services, social media, merchandise sales, and more.

Our intuitive platform also includes tools for analytics, marketing, and user engagement, making it an ideal choice for musicians, bands, and entrepreneurs eager to connect with their audience through a personalized app. Leveraging BuildFire can significantly reduce development time and costs, allowing you to focus on refining your app’s content and user experience.

Testing is an integral part of this phase, involving rigorous checks to identify and rectify any bugs or usability issues. This ensures that the app not only meets the technical specifications but also delivers on the user experience envisioned during the design phase.

Monetization Strategy

After developing and meticulously testing your music app, the next critical step is devising a robust monetization strategy. This strategy is key to ensuring your app is not only a creative success but also a financial one.

Here are some monetization strategies to consider when you build a music streaming app:

- Freemium Model: Offer basic features for free while charging for premium features. This can include higher quality audio, ad-free streaming, or exclusive content.

- Advertisements: Integrate ads into the app experience. Options include banner ads, interstitials, or sponsored content.

- Subscription Model: Encourage users to subscribe for a monthly or yearly fee to access exclusive features, such as ad-free listening, offline playback, and premium content.

- In-App Purchases: Sell digital goods or services within your app. This could be exclusive songs, albums, or virtual goods.

- Partnerships and Sponsorships: Collaborate with brands or artists for sponsored content or exclusive releases, creating a new revenue stream.

- Merchandising: Sell artist merchandise directly through the app, from t-shirts to vinyl, making it easy for fans to support their favorite artists.

- Data Monetization: Leverage user data (with their consent) to gain insights for targeted advertising or to sell to third parties interested in music industry trends.

- Crowdfunding or Tip Jar: Allow fans to support artists directly through donations or crowdfunding campaigns for upcoming projects.

- Live Streaming and Virtual Concerts: Offer paid access to live performances or virtual concerts, providing fans with unique experiences.

- Licensing and Content Creation: Generate revenue by licensing user-generated content or creating original content that can be licensed to others.

- Community Features: Enhance user engagement with paid community features, like exclusive forums or fan clubs.

- International Expansion: Localize your app for different markets to tap into global audiences, adapting your monetization strategies accordingly.

Choosing the right mix of monetization strategies depends on your target audience, the unique features of your app, and the overall goals of your project. By carefully selecting and implementing these strategies, you can create a sustainable revenue model that supports the ongoing success and growth of your music app.

Launch and Marketing

Following the development and implementation of a monetization strategy, the next pivotal phase in the lifecycle of your music app is its launch and marketing. This stage is critical for gaining visibility, attracting users, and ultimately ensuring the success of your app.

An effective launch and marketing strategy not only introduces your app to the world but also builds anticipation, engages potential users, and sets the foundation for a strong user base.

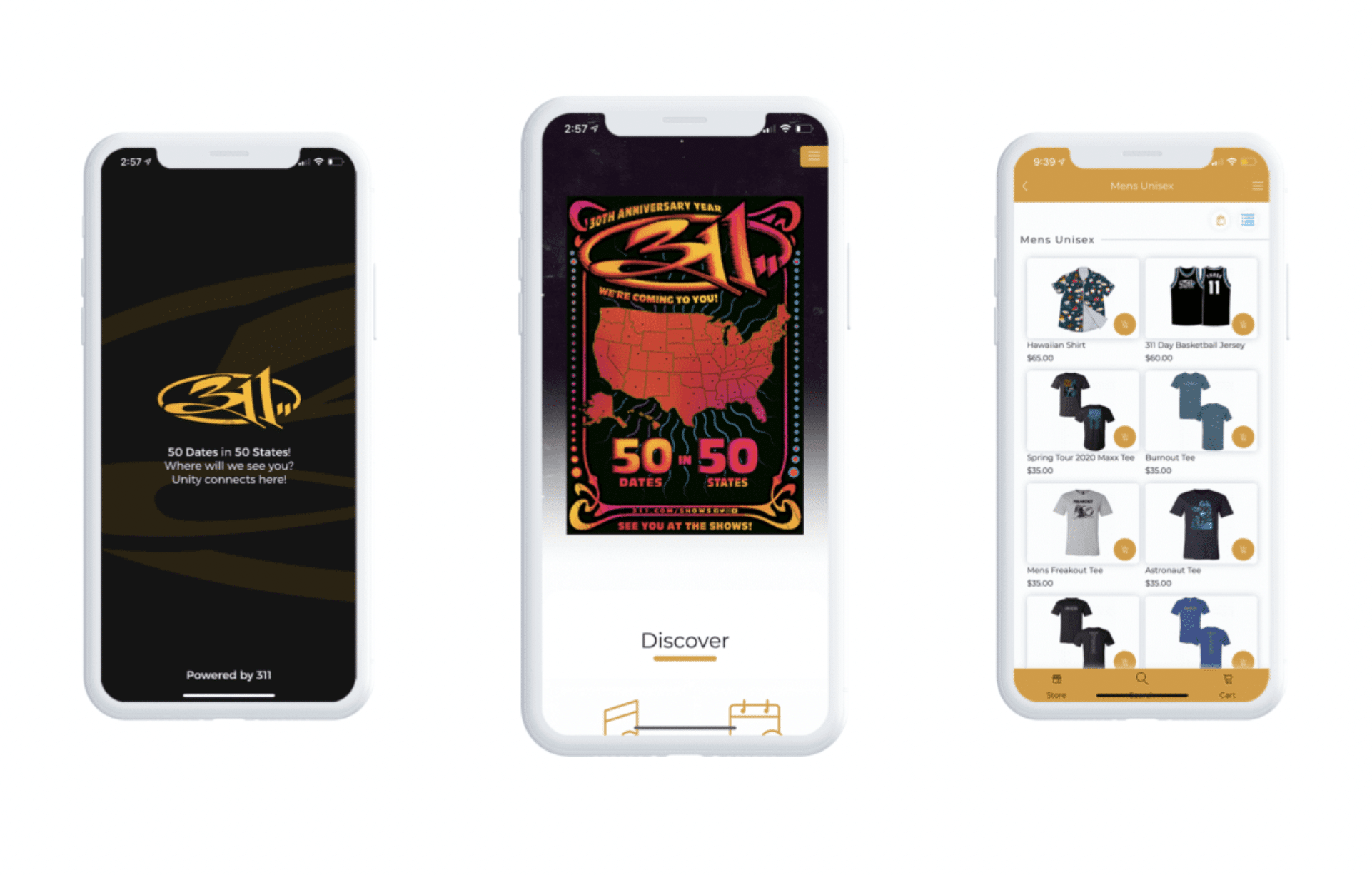

For example, legendary American rock band 311 used BuildFire to create an app for their 30th anniversary tour that comprised 50 states in 50 days.

The marketing efforts for the app were strategically timed to build anticipation in the weeks leading up to 3/11 Day (March 11) when the band was scheduled to perform three days of shows in Las Vegas.

By aligning the app’s launch with a significant event and leveraging targeted marketing strategies, 311 was able to maximize user engagement and downloads. The app served as a powerful tool to enhance the fan experience, offering a new way for fans to connect with the band and with each other, driving up engagement and fostering a sense of community among users.

You can read more about 311’s experience with BuildFire here and use this type of marketing strategy to inspire your own.

Post-Launch Support and Scaling

Even after a successful launch, the journey of your music app is far from over.

Post-launch support and scaling are critical to its long-term success and sustainability. This phase involves closely monitoring the app’s performance, gathering user feedback, and making necessary adjustments to ensure a seamless user experience.

Continuous support not only addresses any technical issues that may arise but also demonstrates to your users that you are committed to providing a high-quality service, which can significantly enhance user retention and loyalty.

User feedback is invaluable for identifying areas of improvement and potential new features that could enhance the app’s value. Engaging with your user base through surveys, feedback forms, and social media can provide insights into their needs and preferences, guiding your development roadmap. This iterative process of improvement and adaptation helps keep the app relevant and competitive in a rapidly evolving market.

Scaling the app is another crucial aspect of post-launch support. As your user base grows, your infrastructure must be able to support increased traffic and data without compromising on performance.

This may involve upgrading servers, optimizing code for better efficiency, or expanding your team to handle the increased workload. Preparing for scalability from the outset can help mitigate growing pains and ensure that the app can handle success without faltering.

Additionally, expanding your app’s features and exploring new markets can contribute to its growth. Based on user feedback and market analysis, introducing new functionalities, such as virtual meet-and-greets, fan-generated content, or augmented reality experiences, can keep users engaged and attract new ones.

Considering international expansion can also open up new revenue streams and increase your app’s global reach. However, this requires careful planning to address language barriers, cultural differences, and local regulations.

Conclusion

Creating your own music app is a complex process—involving everything from initial market analysis and conceptualization to the intricacies of licensing, design, development, and beyond.

Each step of this journey presents its own set of challenges, requiring a blend of creativity, technical expertise, and strategic planning. The goal is not just to launch an app but to create a platform that deeply engages music fans and provides artists with new ways to connect with their audience and monetize their craft.

Fortunately, platforms like BuildFire can significantly streamline the journey. BuildFire’s intuitive app development platform demystifies the technical complexities of app creation, making it accessible even to those without extensive coding knowledge.

BuildFire has a wide array of customizable features, plugins, and templates, enabling musicians, bands, and music entrepreneurs to focus on what truly matters—their vision for a unique music experience—while it handles the heavy lifting of app development.

With the right tools and a clear understanding of the steps involved, turning this vision into reality is more achievable than ever.