311 – The Band

Client Profile

311 is an American rock band that originated in Omaha, Nebraska. Over the past three decades, the band has released 13 studio albums and sold more than 8.5 million records in the US.

Some of their top hits on the Billboard charts include “Down”, “All Mixed Up”, “Amber” and “Come Original”.

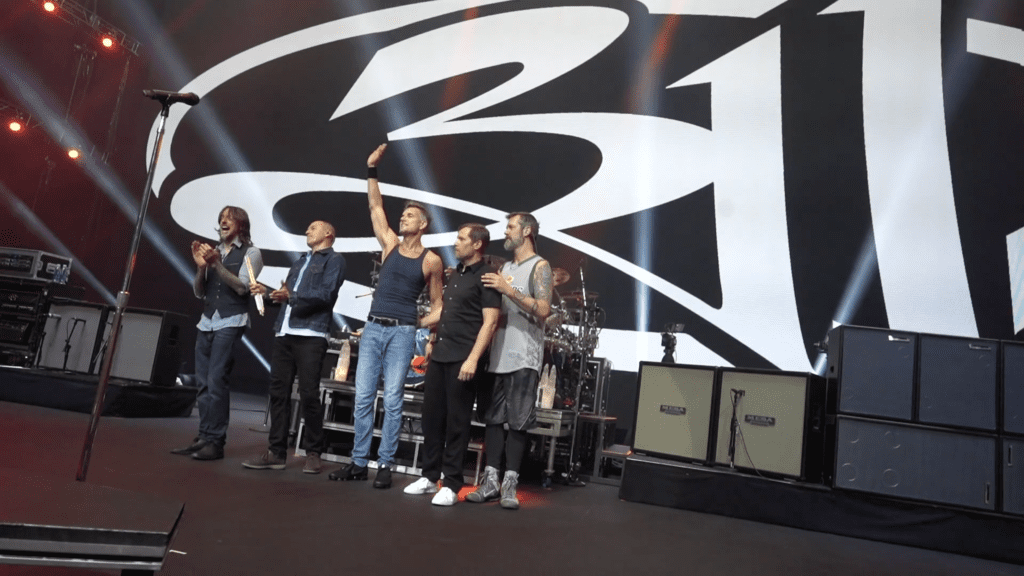

The band is comprised of Nick Hexum (vocals and guitar), Tim Mahoney (guitar), Aaron “P-Nut” Willis (bass), Chad Sexton (drums), and Doug “SA” Martinez (vocals and turntables).

311 is pronounced “three-eleven,” making March 11th (3/11) the band’s unofficial holiday—”311 Day.” Every year on March 11th, the band celebrates by performing an extended concert for tens of thousands of fans. The festivities became so popular that the performances were eventually split over a three-day period in which the band has been known to play over 80 songs.

30 Years of 311

2020 was a big year for 311. The band was celebrating their 30th anniversary wanted to make it a special year for their huge fan base.

They decided to tour the entire country and play a show in all 50 states.

But the performances weren’t going to be enough to make this tour special. The band still wanted to find a way to give something more to their fans, which is when the idea to build an app was born.

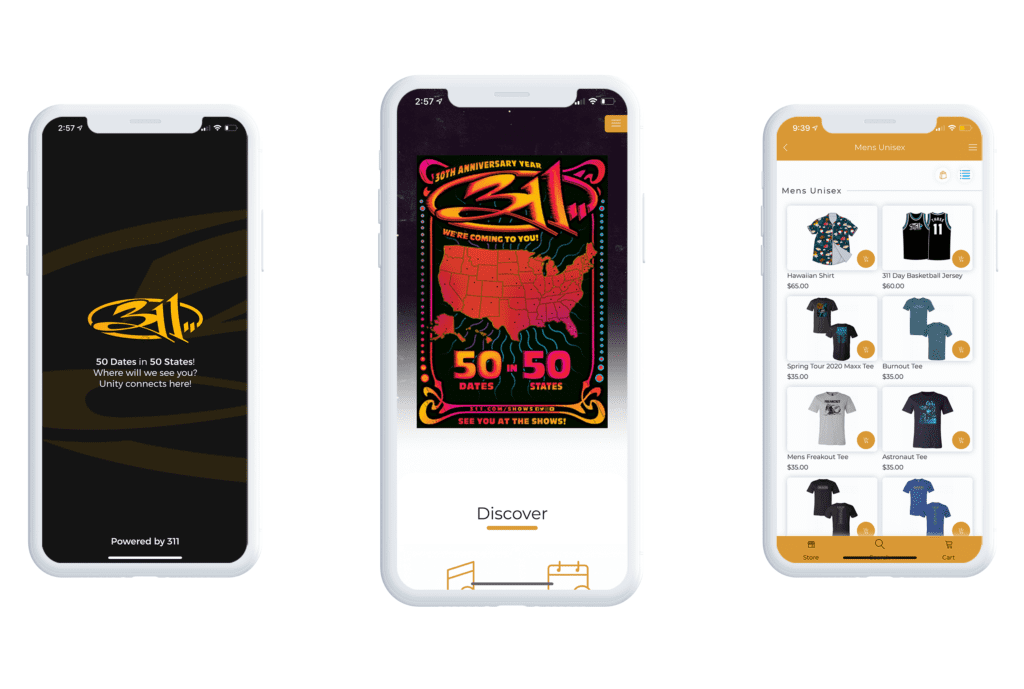

The initial purpose of the app was to make the shows more memorable and give the fans in every state something to do. The fans would have easier access to the band’s content, a story for each show, and have a way to communicate with each other before, during, and after the events.

The Perfect Platform for their Deadline

After finalizing the decision to build an app, the team quickly realized that they had a major problem—time was not on their side. The app needed to be ready by 311 Day on March 11th.

Jake Allard, 311’s marketing manager, explains, “The one initial roadblock was that we only had four weeks until the launch date.”

Nobody on Jake’s team had ever created an app before. After some extensive research weighing their options, they decided that BuildFire’s solution would be the best choice for their needs, especially with such a tight deadline to meet.

“We reached out to BuildFire to talk about 311’s needs and what we wanted to do,” Allard says. “The team on BuildFire’s side really just pulled together, rallied behind us, and got us everything we needed. It was honestly the best way it could have gone, given the time crunch we were on.”

Jake continues to explain how the BuildFire team made it possible for 311 to launch an app in such a short amount of time. “They provided us with all of the tutorials, documents, and taught us what we needed to do.”

Any time Jake had a question or needed some assistance, he would simply send an email or pick up the phone to call BuildFire’s customer support team. The quick responses made it easy for 311 to complete the app within the necessary time frame.

The 311 Mobile App

Once the app was finished, the band planned to promote and announce it on 311 Day. They had three days of shows scheduled in Las Vegas, which was the perfect time to give their fans something special.

But something unprecedented happened. Since the app was already available on the app store before the band promoted anything, the fans discovered it organically.

Jake Allard explains his experience in Vegas before the shows even started. “I was checking [the app] out just to make sure it was working, and I noticed that thousands of fans had already discovered it and downloaded it from the app store.”

Those fans were doing much more than downloading the app; they were taking full advantage of its features. “We were looking at the messaging tab, and fans were already chatting about 311 Day.”

Jake continues to explain how the fans used the app as a way to communicate with each other about different events that were being promoted. Jake says that fans used the app’s message boards to plan where to meet at after-parties and other events away from the actual venue.

“People were chatting on the message board saying, ‘Hey, I’m at this club.’ or ‘I’m at this cocktail bar, come hang out.’ That was really cool. We didn’t really expect people to do that, it kind of just happened.”

In short, the 311 mobile app was a huge success. “We were super happy with it, and the fans loved it. It was great to see people using it even with minimal promotion.”

With the COVID-19 pandemic happening in 2020, the band is obviously unable to tour. But the app has become a way for fans to feel connected with each other and the band.

“I think going forward our goal is to bring some new ideas to the app and develop it into something that’s more of a community hub. 311 has such a tight fan base, so it’s really easy to give them what they need.”

Jake says that fans are currently using the app as a way to talk about previous shows and events that they’re looking forward to once the pandemic is over.

“I would definitely recommend BuildFire to anyone that needs an app. They’re great to work with, super fun, super great team of people. If you ever are in need of an app, definitely reach out to them.”