You’ll agree with me that building a thriving business takes time and effort.

In my opinion, it’s important to have an open mind and learn new marketing strategies for today’s competitive markets.

The truth is, marketing has changed, and smart businesses are leveraging the power of the internet to drive qualified leads and increase revenue.

Without a doubt, online marketing has taken over the wheel. Does it mean that traditional marketing no longer works?

Actually, no.

However, if you’re looking to build a thriving community and attract loyal customers to your website or brand, even if you use native advertising, you still need content marketing – because it’s the easiest way to build trust, nurture a raving fan base, and get repeat customers.

And no matter how well-crafted your marketing plan is, without the right marketing tools, you’ll fail. These tools can come in different forms.

A recent study from Constant-Contact shows that 98% of small business owners already use their website as primary marketing tool

The traditional marketing methods pose the challenge of engaging the customers. Because the ads tend to be pushy, whereas digital marketing strategies (e.g., content marketing, blogging) is welcoming and drives trust to the roof.

On the web, there are several channels that you can leverage to drive customers to your website, like social media, PR, search, display, authority websites, and so on.

Irrespective of the channel you make up your mind to use, you still need the right marketing tool.

Since the sole objective of every business is to make profit, it’s important to reach out to ideal customers wherever they are on the web.

Your customers are your greatest business asset, whether online or offline. That’s why you need to appreciate and answer their questions with helpful content.

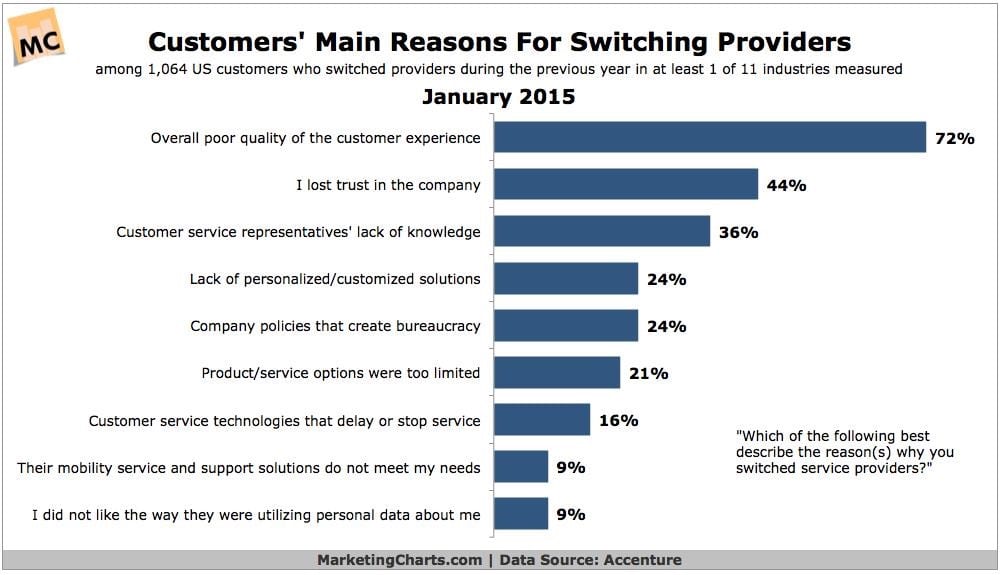

Data from Accenture shows us that 72% of customers have switched providers due to overall poor quality customer experience.

All marketing channels and strategies are effective in their unique ways. The overall success that you get from one channel (say social media) is essentially dependent on another channel (e.g., blogging).

For example, as you generate organic traffic and leads to your business, you need social media to communicate with them, and builds strong relationship via email marketing.

Obviously, leveraging on these lead generation and nurturing strategies only becomes effective and easy when you know and choose the right marketing tools.

As a marketer, do you wish to have “die-hard” customers and fans who will stand for your brand any day?

I know you want customers who will identify with your brand and refer other loyal customers your way. Come on, haven’t you heard that 51% of facebook fans are more likely to buy the brands they’re passionate about?

Building a loyal fan base doesn’t happen overnight.

Trust me, it’s a daunting task. But the rewards are well worth your time.

The 23 marketing tools that I’ll recommend are powerful enough to help you on the path to building trust with your target audience.

Engaging your audience with compelling content is the right step to take.

Create content that your email subscribers will find irresistible. Else, you’ll be overwhelmed at the rate by which several of them unsubscribes from your list.

Recent statistics from Hubspot found that 91% of email users are unsubscribing from a company email list they once enjoyed.

If they must stay, you have to deliver immeasurable value through content marketing.

Of course, content marketing cannot thrive in the absence of marketing tools.

What Are Marketing Tools?

Marketing tools designed to automate repetitive processes, tasks, minimize human errors, manage complexity, build strong customer relationship, maximize effort, and brings your brand to spotlight.

An effective marketing tool should help you achieve either or all of these:

If you desire to be more efficient and productive, then, these marketing tools should be an integral part of your business.

Since you can’t watch over your own shoulders and that of your competitors, manually, these marketing tools does that for you.

Marketing tools cuts across diverse markets. For example:

- Website analytics tools

- Social media management tools

- Conversion rate and funnel analytics tools

- SEO tools

- Marketing automation tools,

- Email marketing tools

…And so on.

In this in-depth article, I want to show you 23 of such powerful marketing tools that you can use to power your lead generation, customer retention, customer service, sales management, and at the end of day, boost your business revenue.

If you’re ready, let’s dive in.

1. Charlie App

Charlie is an attractive marketing tool that helps you create a positive impression when meeting people (especially for the first time).

A positive first impression is critical to winning over that customer, or closing a deal.

In a recent article on Harvard Business Review, by Dorie Clark…

“People may have built up a certain, inaccurate impression of you – you can’t expect to overturn that thinking with subtle gestures, you need a bolder strategy to force them to re-evaluate what they thought they knew about you.”

Truly, you need to work hard to overcome a bad first impression.

If you’re a social person or your job involves meeting with customers and clients, whether online or physically, Charlie App will help you establish a stronger relationship between with customers.

You should know that relationship with your customers is almost everything in business. It can make or mar your strategy.

Charlie scours through 100s of credible sources and automatically emails you a one‐pager on every potential customer/client you’re going to meet with, before you see them. Isn’t it powerful?

This marketing tool (let’s call it app) does this by capturing customer’s bio data, email address, phone numbers for follow up and getting them acquainted with your brand.

Charlie has gone far to introduce personalization in its marketing campaign. This is a campaign where attention are given to customers on-one-one instead of group.

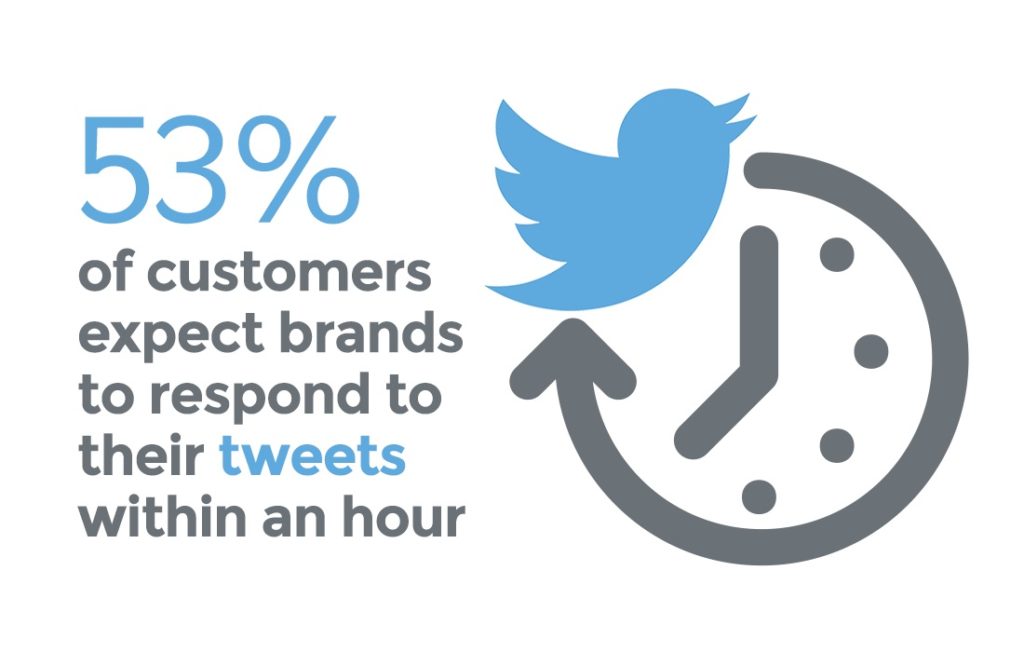

It’s a simple but effective way to answer people’s questions and comments quickly. In fact, 53% of customers want response to their tweet within 1hr.

Don’t make your customers or social media fans perceive you as an unserious marketer, who doesn’t care about them. Use personalization to drive user engagement on social media and during meetups.

2. Oktopost

We’ve all been there – accidentally wishing to make more impact through social media. Yes, we know how powerful social media is, but it seems as though we’re lost.

If you can relate with this, you’re not alone. Oktopost is that social marketing tool you should give a shot.

Oktopost is great for B2B marketers. If you choose a social media tool that’s designed for B2C marketing, your results will be mediocre. Trust me, the plan, approach and features you need are different.

Lee Odden, founder of Top Rank Blog shows the distinction when he said that, “B2B marketers who are goals focused, strategic in planning and action are more effective.”

Oktopost is a B2B social media marketing tool designed to help you power your social campaigns and drive hungry buyers. It enables you to schedule your best posts to multiple social profiles, from a single dashboard.

Stay informed about social media, study the detailed reports on clicks, conversions, and other engagements for each of your posts.

You can also use Oktopost to determine quality contents to share with your audience – and keep them engaged all the time. As you already know, magical things happen when customers derive value for your content and get their questions answered.

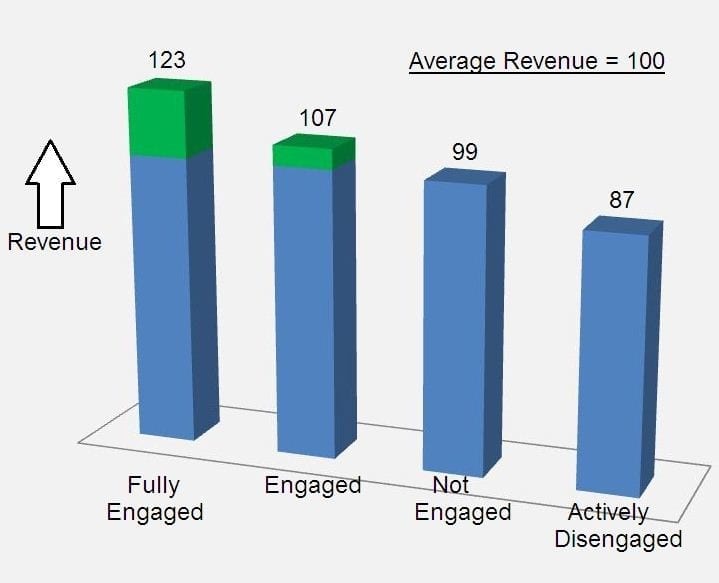

An earlier case study by Gallup revealed to us that customer engagement boost sales and average revenue per user.

.

Truly, it’s difficult to manually determine which type of content your audience prefers you post on social media. But with Oktopost it’s simple. The tool finds relevant conversations and leads you into it naturally.

3. WordPress

If WordPress sounds strange to you, then you’re probably new to blogging, digital marketing, or you’ve been hiding under the Old Harry Rocks in England.

WordPress is a simple and powerful content management system (CMS).

It’s actually a publishing software used mostly by bloggers, authors, digital companies, and content marketers to create and publish content, and build robust website.

These days, starting a business is damn simple. Because you don’t need to have programming skills or hire a professional programmer to build a website for you.

With this free and helpful WordPress software, you can design a website within 20 minutes. There are tens of thousands of free themes and plugins to make your website as professional and dynamic as you want.

The beauty of WordPress is that most authority news channels lives on it. For example, Mashable, CNN, Techcrunch, and more than 60 million other sites started out on WordPress – and I don’t see them switching to Joomla or Typepad anytime soon.

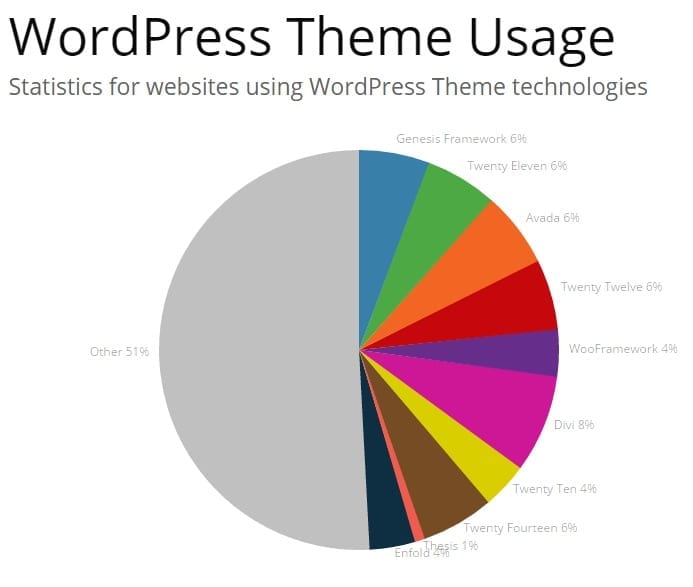

WordPress themes are popular too. Infact, 51% of marketers are now using WordPress themes to power their blogs.

No matter what you’re looking for in a website, I can assure you that WordPress is powerful enough to support it.

Even if you operate a brick-and-mortar business, you can always build a website and use it to attract motivated customers on the web.

4. Crowdfire App

Launched February 2010, Crowdfire is a social media engagement app for Twitter and Instagram. It’s great for managing user accounts. It’s built to generate automated answers to questions often asked by your fans, especially on Twitter.

If you get Crowdfire, you’ll never be intimidated by your Twitter and Instagram accounts irrespective of the numbers of followers.

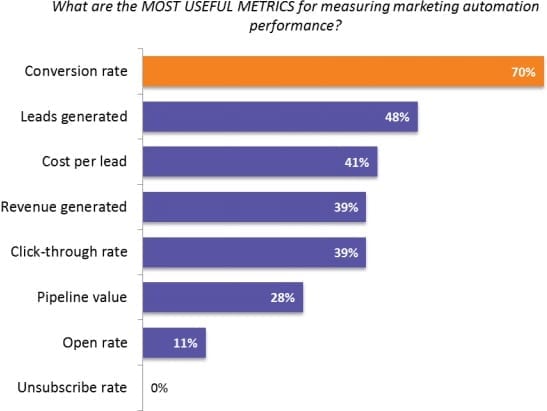

Email Monday confirmed that getting 70% conversion rate is as a result of using marketing automation tool like Crowdfire.

You can collect useful data and insights about inactive users and those about to unsubscribe. You can clean up those that ain’t converting and ignite fire inside the inactive ones.

5. Medium

Medium is a community of ardent readers and writers offering unique perspectives on ideas they’re passionate about.

Typically, Medium is a tool used by authors, publishers, bloggers, and writers.

Hey, these professionals don’t think alike. More importantly, the goal of a blogger is quite different from an author.

For example, a blogger is looking to build an audience via his blog, whereas an author may not even have a blog. He was to get on the bestseller list.

Does that make sense?

Primarily, you can use Medium to amplify your content: reach hundreds and even thousands of people, republish your old posts and garner more social shares.

Medium is very good and helpful for beginners and intermediate writers.

You’ll benefit from the ready-made audience, and this will show in the number of views your first post will generate.

People can subscribe to get updates when you publish new post on Medium. You’ll agree with me that this is another viable way to put email marketing to good use.

Don’t you think so?

6. Wistia

While no two video streaming sites are created equal, the goal and motivation behind using one often are.

If you have awesome video to share, I’m sure that your mind will go to YouTube, right?

Yes, YouTube is powerful, great, attractive… it deserves all the accolade.

But, YouTube hasn’t dominated visual streamings online. If you aren’t concerned much about views as you’re with conversions, then Wistia is a video marketing tool to rely on.

If you want your audience to spend more time engaging with your video content, then, you have to use Wistia. Because, it has so many controls, features, and welcoming ads which I’m sure your audience will enjoy.

Would you like to know how your videos are engaging your customers? Wistia provides a clearer analytics and serves you the right video metrics on a platter.

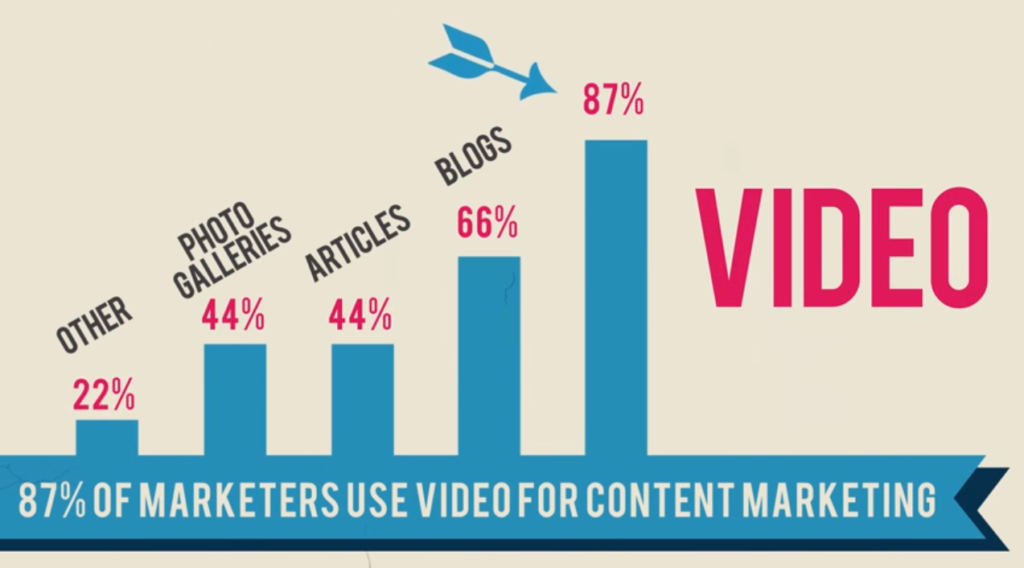

Video content still remains one of the most effective ways to engage prospects.

Hubspot stated that 87% of marketers today use videos in their marketing campaign.

In the past, creating a marketing video was difficult. But today, you can create professional videos at an affordable rate. It’s no longer about the cost of purchasing video production equipments, but the expertise.

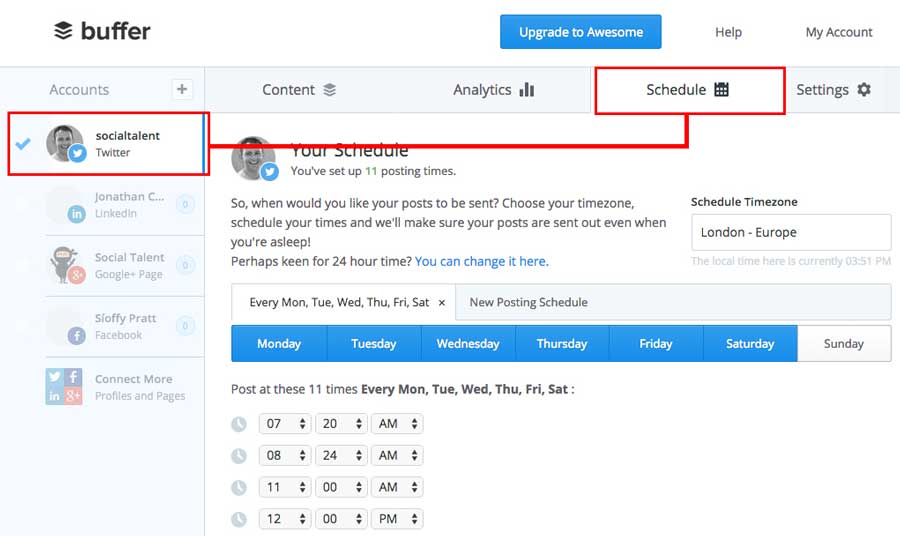

7. Buffer

I know a few brands that have built thriving businesses, though they didn’t have a Facebook fan page, Twitter account or participate in any form of social campaigns.

As you’d expect, the journey from $0 in profit to $100,000 per year was a hard nut to crack.

Come on, don’t shy away from social media. Millions of active user are waiting for you on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and the like. Social media can play a key role in your customer service.

Jayson DeMers highlighted the 7 reasons why you should use social media as your customer service portal.

In my own opinion, there is no effective marketing today, without social media.

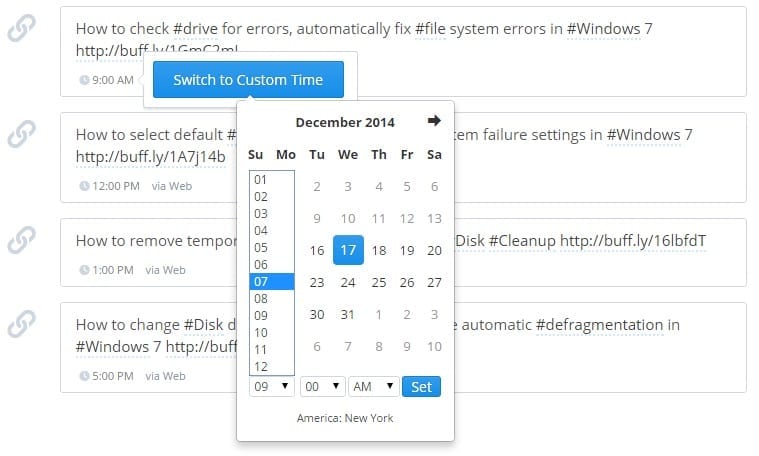

Buffer was initially a simple app for scheduling Twitter posts, but it’s become a more powerful tool that helps you save time managing your social media.

You don’t have to be there physically to keep your social media users engaged.

Buffer will act as your representative, while you make out time for other pressing and urgent matters that will impact your revenue.

Buffer app works tirelessly at the backend to engage your audience. You can schedule as many posts as possible.

You see, as your customers get busy with your brand on social networks, they’ll feel excited about your product.

This engagement strategy enables you to to nurture your leads without coming off offensive or pushy, which is exactly what you need to build loyalty with customers.

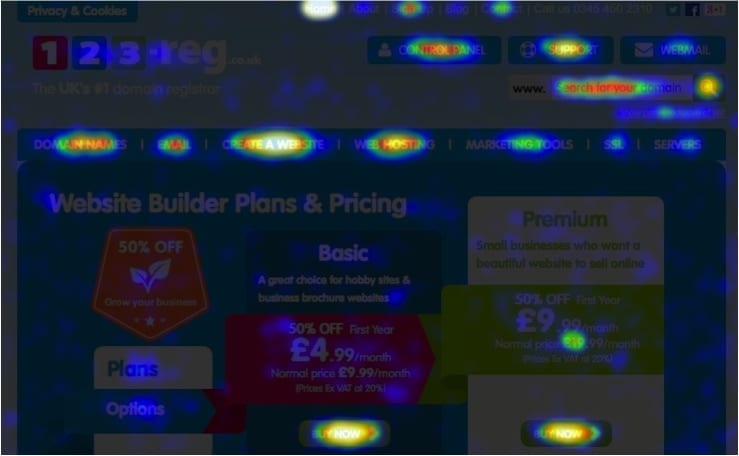

8. Hotjar

If you are looking for a website optimization tool, search no more. Hotjar is the all-in-one analytics and feedback tool.

Understanding your web and mobile visitor is critical. Nick Leech listed the 5 proven ways to understand website visitors. One of such is by conducting a Five Second Test.

The test is easy. You could do it manually with your friends and family.

Better yet, enter your URL into the fivesecondtest.com, and let other people will carry out a test on your site for free. To make it win/win, you should return return the favour and do a few five second tests of other people’s websites as well.

The Heuristic test (where you involve your colleagues) is effective too. But the easiest way to pinpoint how visitors are interacting with your website is by using a heat map and recording tool.

Hotjar is a powerful and easy marketing tool that shows you how your web and mobile site visitors are interacting with your website. You can use the tool to find hottest opportunities to optimize for conversions.

As a smart marketer, you need to know what’s trending in your landing page.

From capturing users behaviors with Hotjar, you will get insights of what they truly care about.

9. Simply Measured

Are you tied down by big data?

Simply Measured believes that social marketing should be simplified, and not tied overwhelming with all the data. Ideally, the social data should drive your marketing.

Simply Measured provides an easy social media analytics and measurement solution for small and mid-size companies.

Who are your Twitter followers and what do they care about?

Use the measurement platform by Simply Measured to fuel your social campaigns and gain deep insights in your fingertips.

Simply Measured is provides Facebook analytics, Twitter analytics, and more. You also get to know how healthy your Instagram fans are and what’s trending in your Facebook fan page.

Yes, being sensitive to what is trending in your social media accounts guarantee that you acquire customers from these networks, especially Facebook.

Simply Measured rich features enable you to compare your Facebook fan page with your competitors – to know their weaknesses and strengths. Give it a shot today.

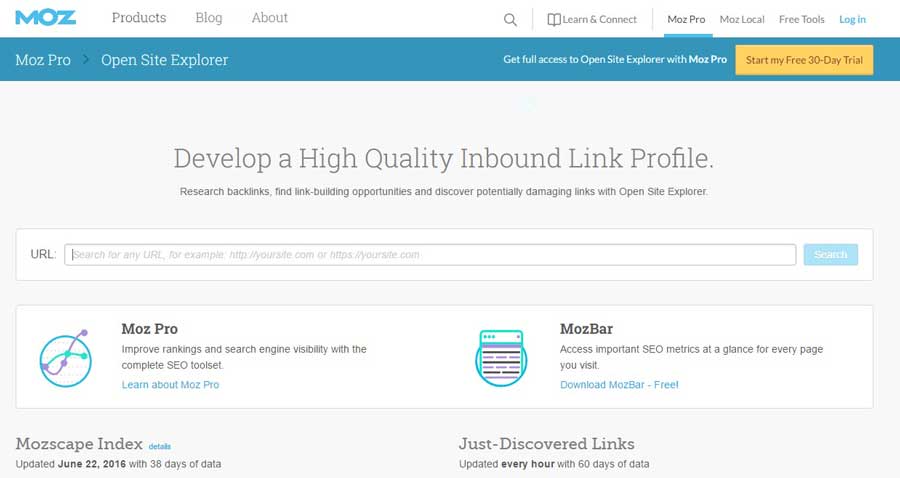

10. Open Site Explorer

Open Site Explorer is a search marketing tool that enables you to develop a high quality inbound link profile.

For example, OSE helps you research backlinks, find link-building opportunities and find potentially damaging links.

Specifically, you can determine the number of backlinks your website or web pages have generated over a period of time (say 60 days).

Once you’ve found damaging links, the next vital step is to get rid of them. Else, your search rankings may drop.

Optimizing your web pages can dramatically improve your search rankings and drive qualified traffic to your website, especially when your content page ranks at the top of organic results.

11. SumoMe

Website traffic is the fuel that powers your online business machine. Without traffic, you’re going to fail. Sorry.

In a recent article on the Huffington Post blog, Ian Mills summarized the importance of website traffic.

In Mills’ words,

“The single aim of all marketing efforts is to increase sales and in order to achieve this online, your website needs to have traffic to convert into a sale or a lead. You can’t convert anything without traffic, and without conversion your traffic is pointless.”

As you read this article, marketers are actually looking for ways to generate and grow website traffic.

If you’re one of them (well, I am), then Sumome is the simple but powerful marketing tool to leverage.

Adding social sharing buttons on your posts alone can encourage people to share it. However, without Sumome, you’re allowed to customize the appearance of your sharing buttons to blend into your theme.

One of the greatest features of SumoMe is its mobile responsiveness. All of the accompanying tools that Sumome provides will fit into any mobile screen – and engage the audience.

Are your web visitors actually reading your blog posts?

It’s hard to tell. Really.

The Content Analytics, a tool in the SumoMe warehouse will give you rich insights in this respect.

When building social media campaigns, there is no room for assumptions. Don’t assume that your posts will be shared. You may not like the end result.

Again, if you place your call-to-action wrongly, you won’t get people’s attention.

To know where to place your call-to-action, you need to analyze user behavior using Sumome’s tools.

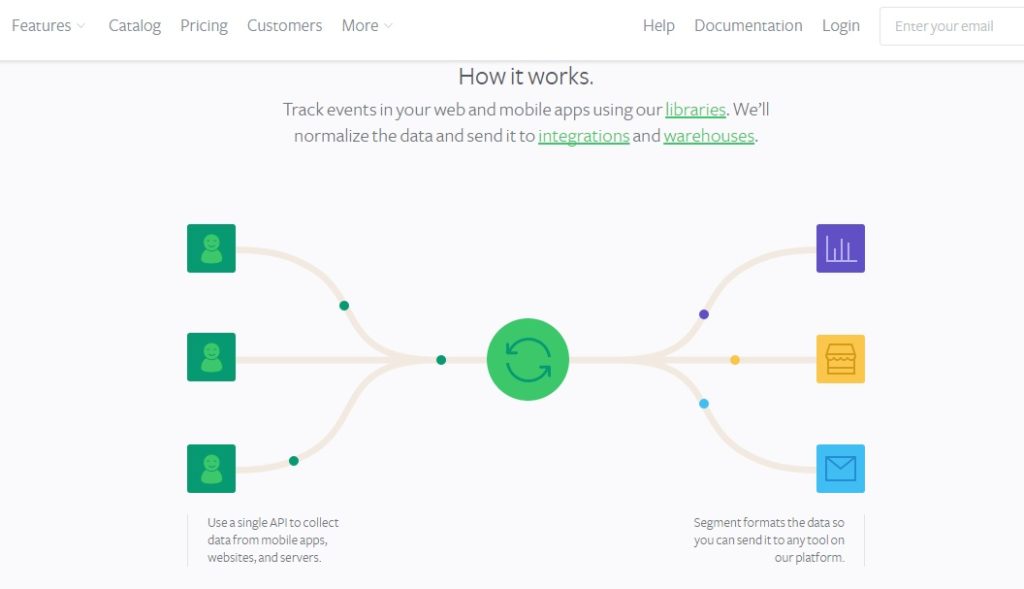

12. Segment

Segment is an analytics software made simple.

Segment captures customer’s information through the API and makes them easy to understand and beneficial for your business. Here’s how it works:

The processes done in your website and mobile apps can be captured and kept in the Segment Libraries, for your use.

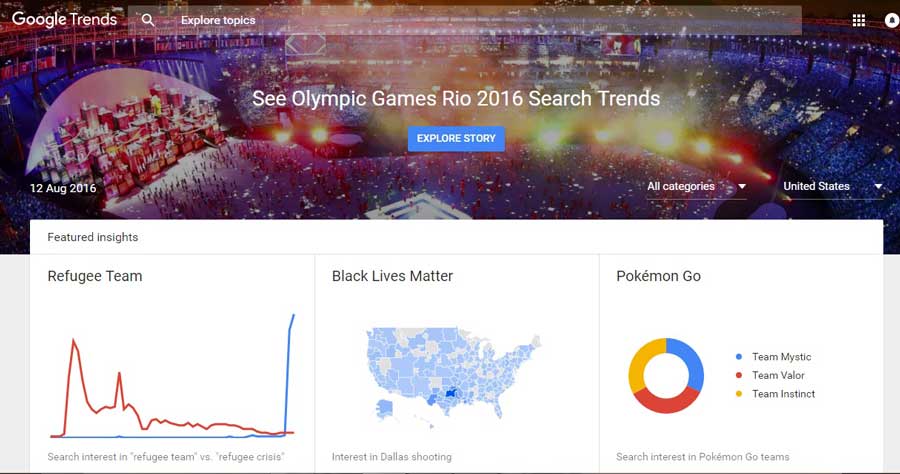

13. Google Trends

Google Trends is a solution that shows the graphical representation on how a particular keyword or topic is trending in US or globally.

It’s a free Google services for topic analytics. It’s very helpful in market research and web surfing behaviour tracking.

For example, let’s see what’s trending right now around the world.

With this tools you can know what the world is thinking about your product and services.

You definitely need Google Trend.

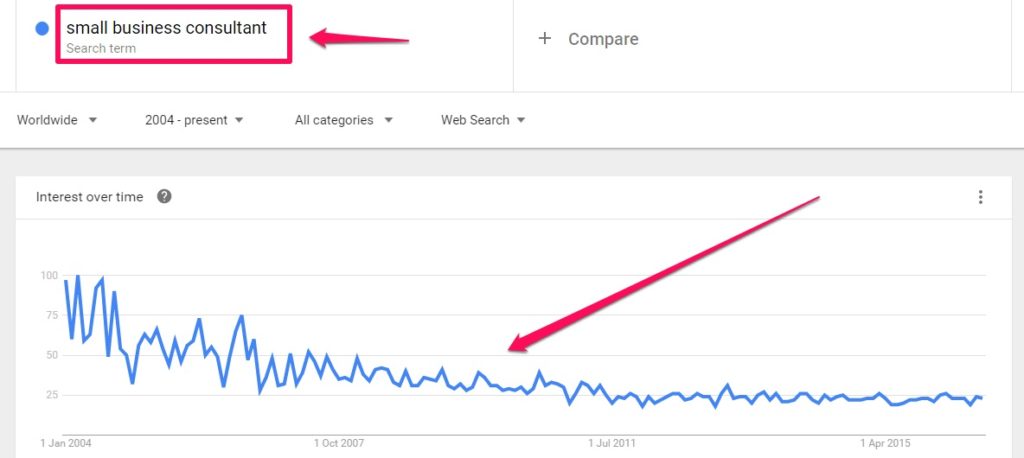

For example, if you’re a small business consultant and wants to know how popular the market is, all you’ve to do is input the keyword into the Google Trends search box and search it.

Sadly, from the graph below, you can see that the demand for “small business consultant” is constantly going down. It’s now left for you to decide whether to move on or quit.

14. Blog Topic Generator

Do you know what your next blog post topic is?

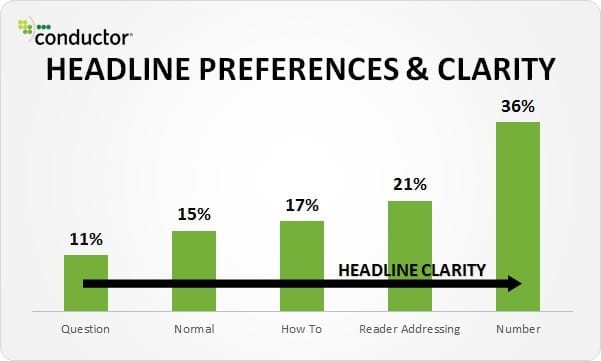

How do you craft the headline? Truth is, the headline is the most important element of your content. According to Brian Clark, founder of Copyblogger, 8 out of 10 people will read your headline.

If you’re stuck right now and don’t know what to write about, you’re not alone. You can use the HubSpot’s Blog Topic Generator.

To get started, simply enter your keywords into the blank spaces. Then click on the “Give Me Blog Topics.”

Next, the tool gives you a Week of Blog Topics:

Note: These topics are analyzed based on the keywords. The chances of going viral if you promote your content is high. You can see how clear the headlines are.

Moz confirmed that clear headlines with numbers are preferred by users.

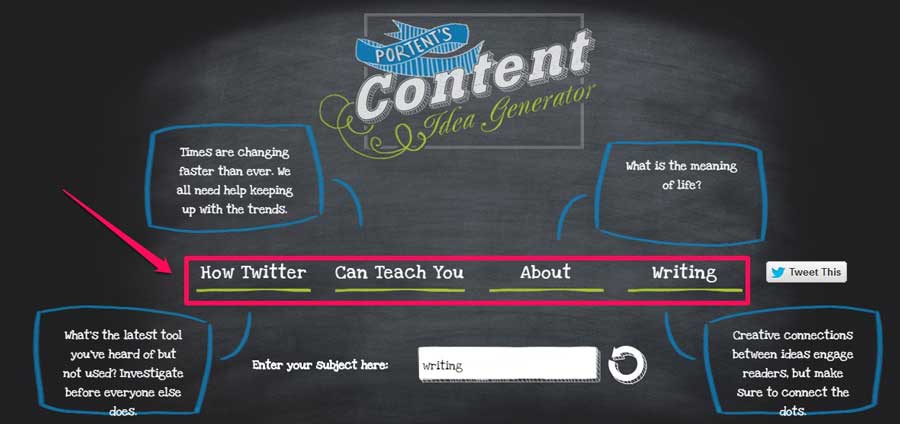

15. Content Idea Generator

Portent’s Content Idea Generator functions in a similar way as HubSpot’s blog topic generator.

The tool generates trending and irresistible blog post titles, so you don’t have to. Simply enter your keyword in the space provided and click on the white arrow.

Next, the tool gives you an idea for a blog post. It may not be grammatically correct, hence, you need to tweak it.

Content Idea Generator is your content creation guide, when you’re looking to get more content out there – but don’t have the time to always write headlines from scratch.

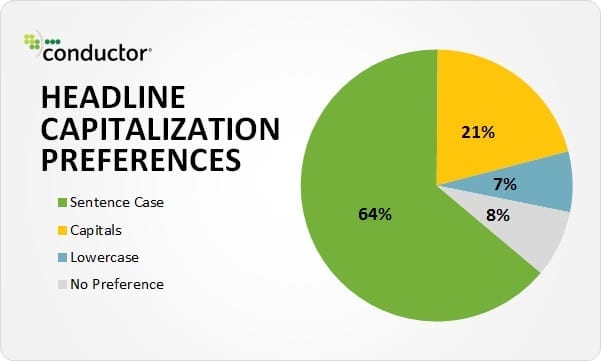

When inputting your keywords, avoid CAPITALIZATION. Else, the tool will return headlines that don’t read well.

Moz confirmed that using Sentence Case in headlines convert 64 % while ALL CAPS convert at 21%.

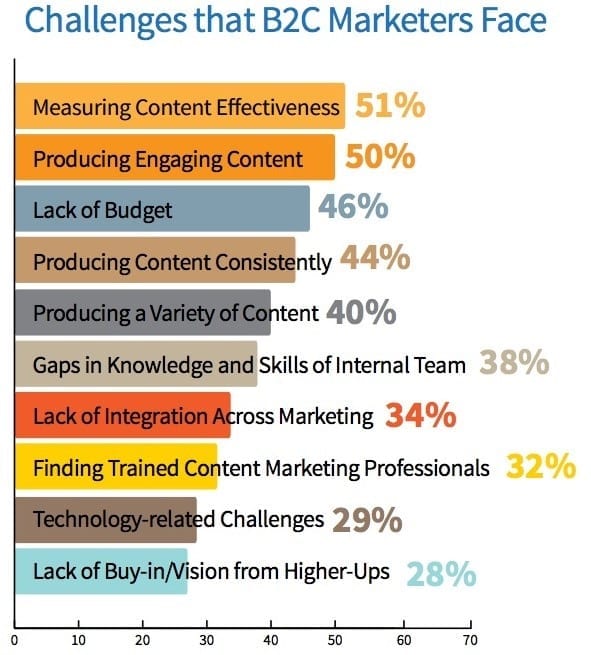

It’s ironic, but despite knowing how powerful content is in today’s digital marketplace, so many marketers have a hard time creating compelling content.

Creating a successful content marketing strategy is almost difficult, without making room for content creation and distribution. Let this tool guide you.

16. Evernote

It’s time to remember everything.

Evernote is a cross-platform marketing app, developed for taking note, organizing, and archiving ideas. These notes can be in form of formatted text, full webpage/excerpt, voice memo, photographs and even handwritten ink.

Jotting down few notes whether on a business call or meeting, helps you remember and make smarter business decisions.

But instead of using pen and paper, use Evernote app on your mobile device and you’ll be fine.

When taking notes, they’re immediately updated on all your devices and stored in the cloud. So accessing your ideas from anywhere won’t be a problem.

A recent study found that 54% of the most effective B2B Marketers have a documented content marketing strategy.

As we all know, ideas rule the world. Lots of successful entrepreneurs like Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook started with an idea. I’m sure your business was a simple idea that you’re passionate about.

With the search button on Evernote, it’s very easy to find any note you’ve saved, even words on PDF documents. It also allows you to share your ideas in notes with your team.

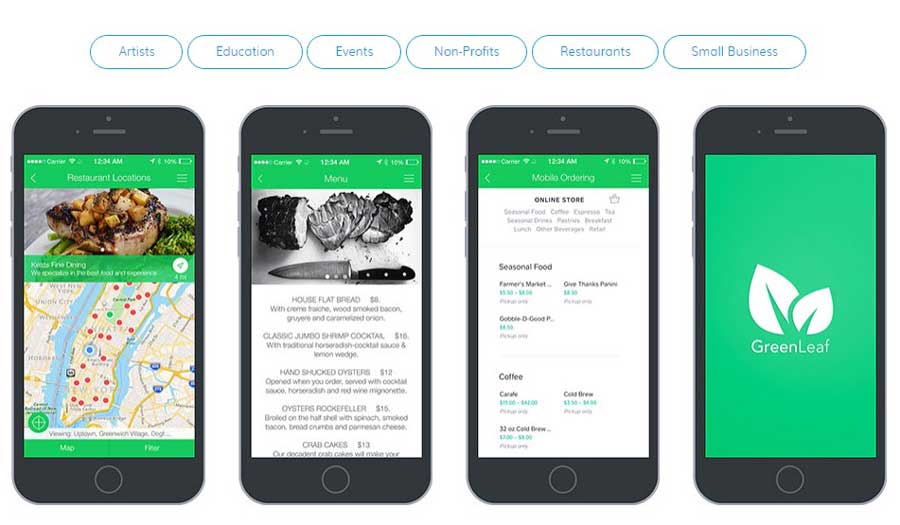

17. Buildfire

Buildfire is the easiest way to build mobile apps. And these are not your average mobile apps – you can check out the features.

The use of internet via mobile devices is always on the increase. As a marketer, can your customers access your products through their mobile devices?

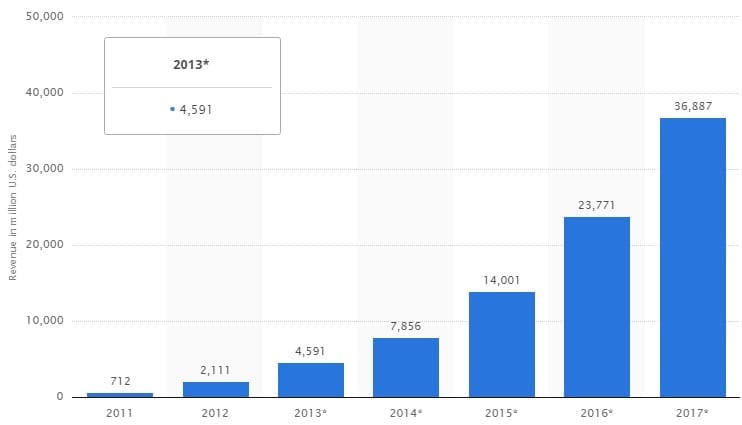

According to a statistic by Statista in 2012, mobile in-application sales was predicted to exceed $36,887 billion in 2017.

In-app marketing is too competitive with over 1.8 million mobile apps already available on Google Play store and Apple store respectively.

If you wish to leverage mobile apps in your marketing, you need a robust drag and drop builder like buildfire.com.

Irrespective of what your business looks like, Buildfire has a variety of templates that will suite your business. Funny enough, you don’t need programming skills, yet, your mobile app can be reader in 15 minutes.

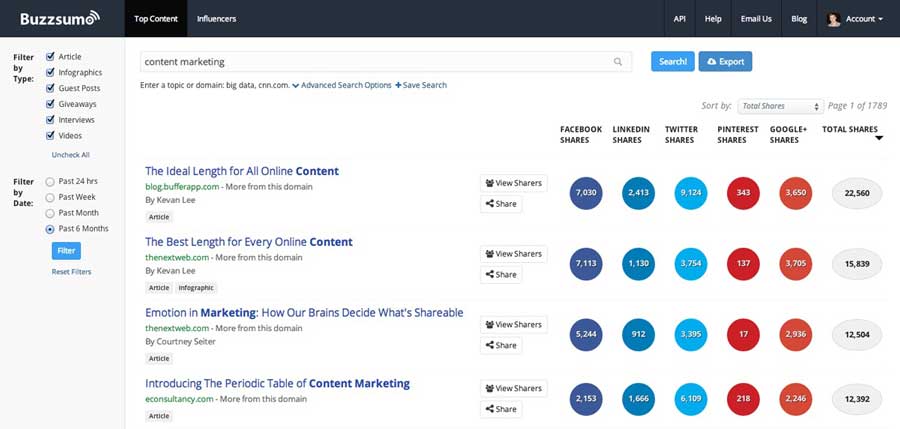

18. Buzzsumo

One of the reasons why most brands embrace content marketing is to create brand awareness. And this can only happen when you leverage social media.

But the surprising fact is that only 38% of B2B marketers are reported to have an effective content marketing. How sad?

How effective is your content marketing?

If you’re looking to improve performance, and get your content shared across social networks, Buzzsumo is the right tool.

Buzzsumo is a powerful tool that scours the entire web and shows you content that generated the most social shares – for a given keyword or topic.

You can also use the tool to identify the social media influencers who can amplify your content reach.

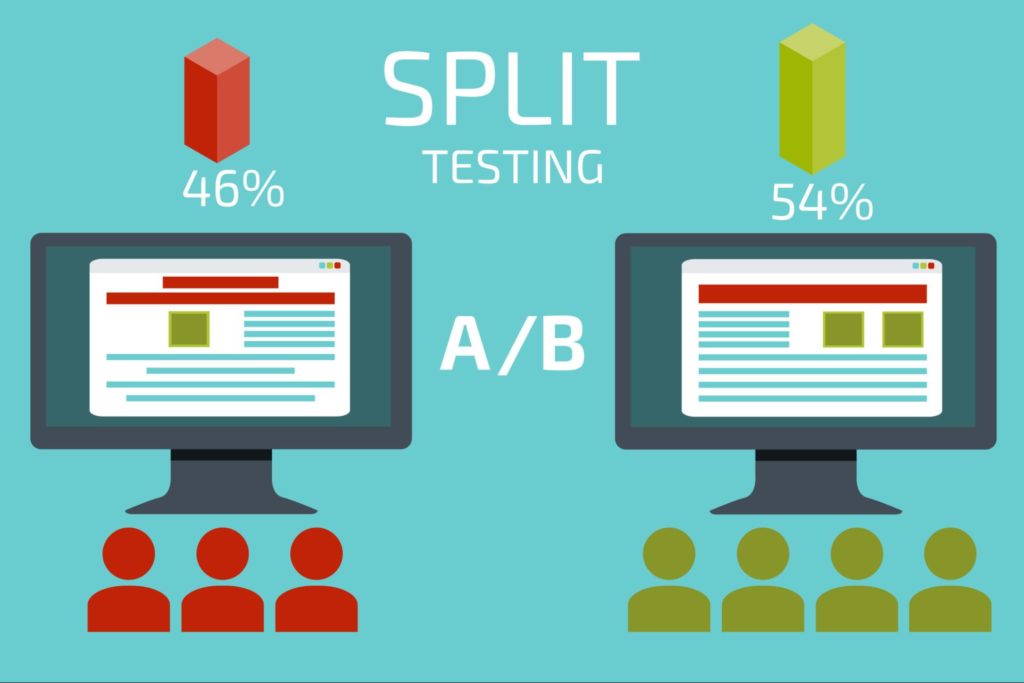

19. VWO

Do you wish to get the best out of your web marketing?

With different marketing ideas and strategies available, integrating them into your business can be confusing at times. Because what worked for Mr A. may not work for you.

To eliminate guesswork from your web marketing campaigns, you should split test.

Knowing firsthand what people want from your landing page or ad copy (and why) is a huge step toward implementing a successful content marketing strategy.

That’s why you need VWO – the A/B Split testing software for marketers that work. Use VWO to tweak, optimize and personalize your website with minimal IT help. You can conduct A/B testing, Url split testing, multivariate.

What an easy way to ascertain the best strategy that works for you.

VWO also provides you with real user feedback, and analysis of your landing page performance.

This tool keeps you informed with analysis on your revenue, visitor segment metrics – improves your audience targeting, and uses personalized content to engage your audience.

This case study at Unbounce showcases several brands that uses split testing to improve their conversion rates and increase revenue.

20. Contentful

It’s always been difficult to get the right CMS that provides seamless word processing tasks.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise to know that Contentful is a content management developer platform with an API at its core. The developers have done a great job – and users are happy with this solution.

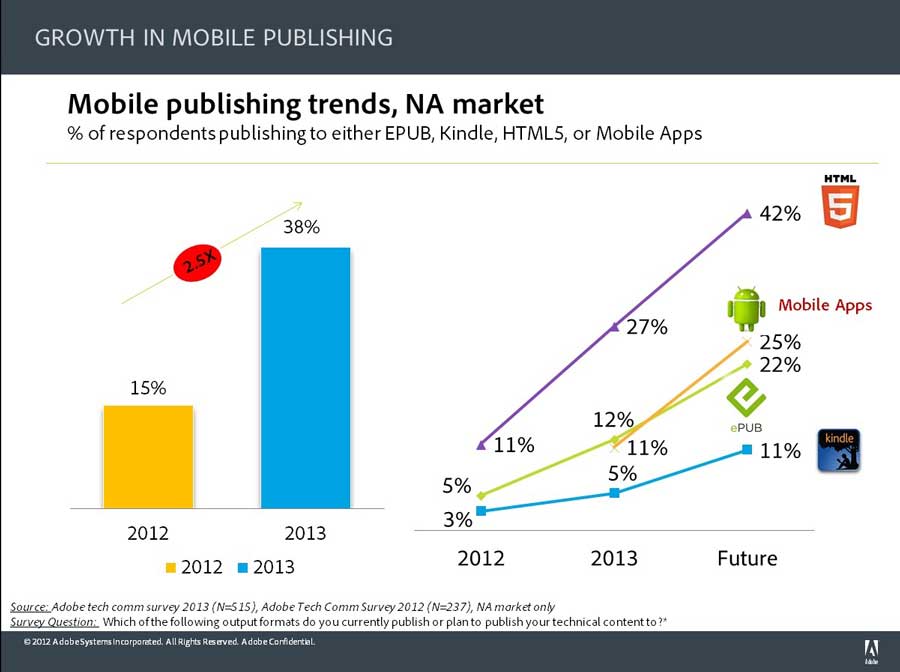

It’s clear that content consumption is stronger on mobile than PCs, as more people use smartphones to browse the internet.

Infact, marketers are now creating content in mobile format, hence, multi-device publishing seems to bring good results.

What CMS do you recommend to support true multi-device publishing?

Contentful is an easy to use content editing tool, with the adjustable platform that integrate with the best CMS features. This this tool, you can increase your publishing speed and efficiency.

Top brands like Nike, eBay and Red Bull have succeeded with Contentful. You should try it.

21. Pixxfly

If you’re a marketer whose content needs a little polish to get results, don’t worry. With Pixxfly and some actionable tips from established writers, you can create a truly impressive content that people will love.

Pixxfly is an action-driven tool to power your content marketing. It’s time to unleash the viral potentials of your content.

This all in one solution supports content distribution, syndication, publishing, PR, video, research & content performance measurement.

And talking about the Content Distribution feature, which allows you to upload your marketing videos, images, podcasts, infographics, and press releases and schedule distribution to one or multiple social media accounts with one click.

A multi-tasking marketing tool that simplifies every aspect of your content strategy.

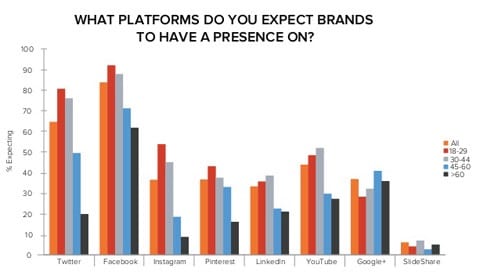

Pixxfly helps you to engage your customers easily directly on the major social platforms. This is so important, because most customers expect to have their brand’s presence on different social platforms.

With over 1,000 top news sites, social sites, journalists, and database made accessible for your content to be shared – from a single dashboard.

Pixxfly keeps tracks and measures the effectiveness of your content across all your social accounts – and notifies you of your most effective campaign, with detailed analysis.

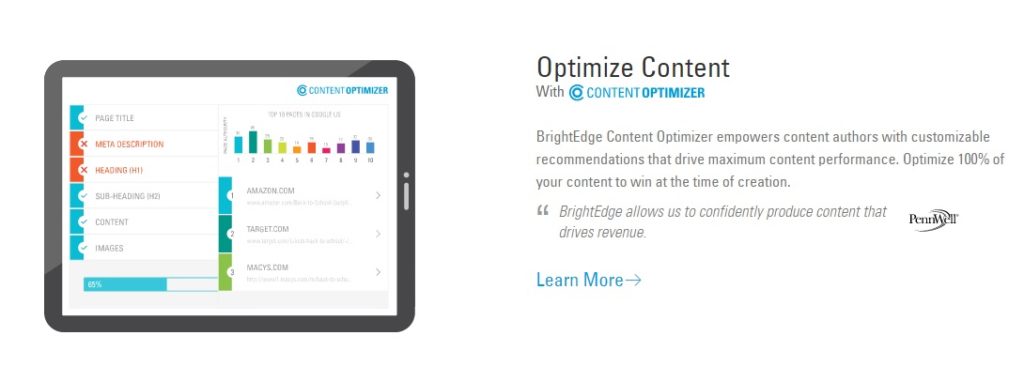

22. BrightEdge

A lot of marketers and brands spend so much into digital content marketing with the hope of generating quality leads and customers.

Sadly, 51% of these marketers fail because they can’t measure content performance.

But with BrightEdge Content Performance Tool, you can plan, optimize and set up campaigns based on actual content performance. Do you know that your content is competing against billions of pages?

In case you don’t know, you need a tool that can target demand, optimize content, and measure results.

With BrightEdge, you can eliminate guesswork from your content strategy, and run content by the numbers. As an Enterprise SEO platform, you can use content insights to optimize your pages and improve search rankings.

According to BrightEdge, last year marketers invested over $135 billion in the creation of digital marketing content.

As you would expect, this content has limited value unless it’s well optimized and distributed. More so, it must be connected to ROI. You can use the Content Optimizer to polish your next content.

23. MailChimp.com

Is the money in the list?

Yes, to an extent, that phrase is correct.

However, a list of subscribers means nothing unless you nurture them and make them trust you.

In all, email marketing still remains one of the best ways to engage and retain customers through personalized emails.

According to the 2013 MarketingSherpa Email Benchmark Survey, “67% of marketers say that delivering highly relevant content is a strategic goal their organization wants to achieve through email marketing.”

Several studies have shown that it takes more resources to acquire a new lead than to retain an already existing one.

That being said, you need to get serious with email list building. Start today.

Don’t you think it’s high time to send better emails and sell more products.

MailChimp is an email marketing tool that you should use to build a customer acquisition strategy for your brand.

At the surface, MailChimp looks rather simple, but it’s powerful. Check out how you can use MailChimp to grow your brand.

The tool uses your customers purchase history and behaviors to segment your list – so that you can recommend relevant products to specific segments and boost your conversions rate.

What a powerful way to personalize your email campaigns for your subscribers?

Funny enough, this is what 75% of your customers want you to do.

Conclusion

Digital marketing is thriving for most brands thanks in large part to the different social channels and marketing tools.

Okay, we can’t forget mobile marketing, which has swept the entire web like a rushing flood.

Indeed, when you dig into marketing data, any notion that social media, email, search, mobile marketing, or PR is “dying” with consumers is a joke.

Evolving – yes. Dying, absolutely not.2

Developing and maintaining a good marketing campaign takes time and effort.

When it looks as though nothing is happening to your business, you may need to re-evaluate your strategy and marketing tools.

Because at the end of day, your results is dependent on how you adapt to changes in the marketplace to align with consumer behavior.