Social media – the undisputed king in the marketing domain… And then there’s email. Think of it as a grandparent to social media marketing. Don’t be fooled, it’s still reliable if used the right way. Today’s marketers may not be as email savvy, nor do they consider it to be a “cool” way of contacting clients, however, it has stood the test of time and proven itself to be an effective method of communication.

As long as you’re using it right, email is still one of the most valuable and targeted channels for reaching your audience. It’s also a great way to make money.

You can use your email marketing strategy to promote your app. You can also communicate with clients about your white label services or anything else that adds value to their needs.

Here are some of the best email marketing tools to ensure you hit the mark every time.

HubSpot Email Marketing

HubSpot offers a reliable and feature-packed email marketing tool that’s suited for growing businesses — for free. You can create professional marketing emails that engage and grow your audience with the easy drag-and-drop email builder. With the drag-and-drop email builder, you don’t need to wait on IT or designers for help. On top of the free email tool, you can use the HubSpot CRM for free to create tailored touch-points for your customers. HubSpot Email is automatically connected with the HubSpot CRM, so you can tailor relevant emails based on any details you have — such as form submissions and website activity. Using the CRM, you can include personalized content in your emails, like first name and company name, to ensure your contacts feel like they are being personally addressed, all while tracking

email activity in the CRM.

The HubSpot email tool is free for up to 2,000 email sends per month, with upgrade solutions starting at $50 with Marketing Hub Starter.

Pricing:

FREE

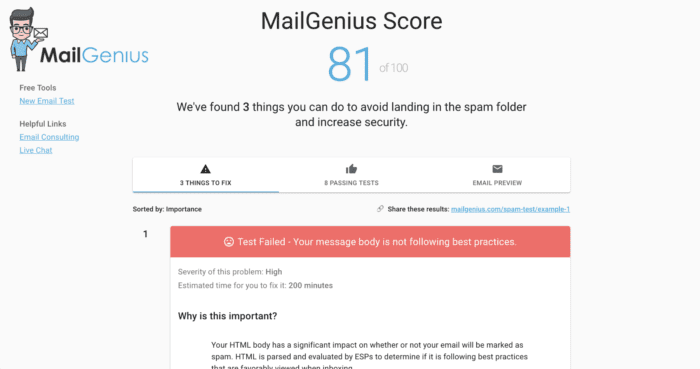

MailGenius

MailGenius is a free tool that inspects your emails and finds possible triggers that might get your message sent to the spam folder. You can run a deliverability test to ensure your email actually reaches your recipient’s inbox. Otherwise, it won’t be opened.

The tool lays out all the things you can do to avoid landing in the spam folder along with actionable advice and explanations on how to fix any issues you may have.

Even the best email copy and subject line can only go so far if your message lands in spam. Deliverability problems can severely impact your email marketing campaigns, so it’s important to be proactive and run a test to ensure you’re following best practices.

Pricing:

FREE

Litmus

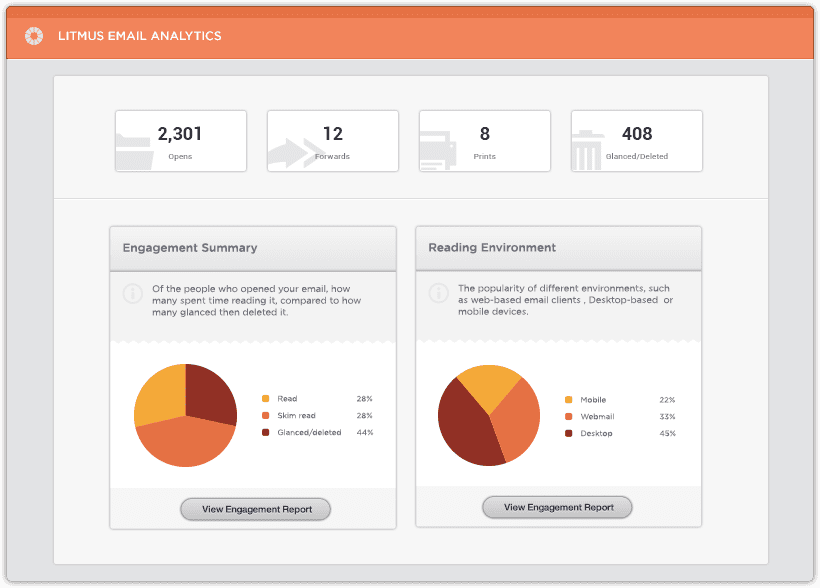

Litmus is a highly versatile tool through which you can use to test and track email. You can test your emails in traditional web-clients and also popular mobile devices like Android, Apple and Windows.

Use Litmus for render testing and make sure your creative is optimized for any given device. You can test more than 40 clients and devices and with a mere click, Litmus can generate a test email to an address so you can send it to your ESP. Within minutes you’re going to see desired browsers, ISPs and devices.

Want your link testing stream-lined? Put the email through a landing page test and within minutes, you’re going to get an overlay of that email with complete results for every link. The ESP tracking report inserts a tracking pixel in your email and you get subscriber data such as how and where the email was opened, how much time the user spent time reading it, and if it was organically forwarded or printed.

Pricing:

Litmus comes with a free 7-day trial, while the premium version can be had for $399 a month, $149 for the Plus version, and $79 for the basic version.

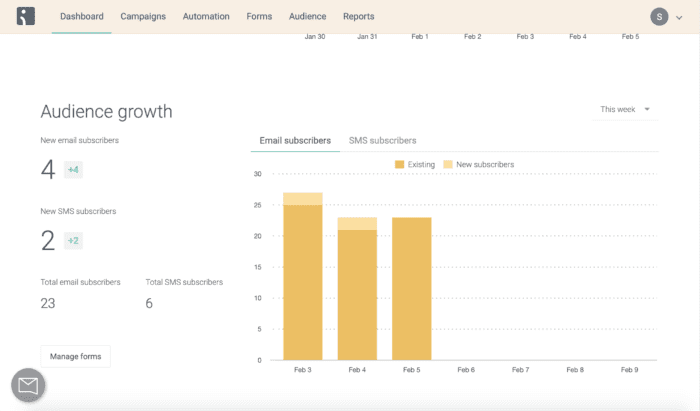

Mail Chimp

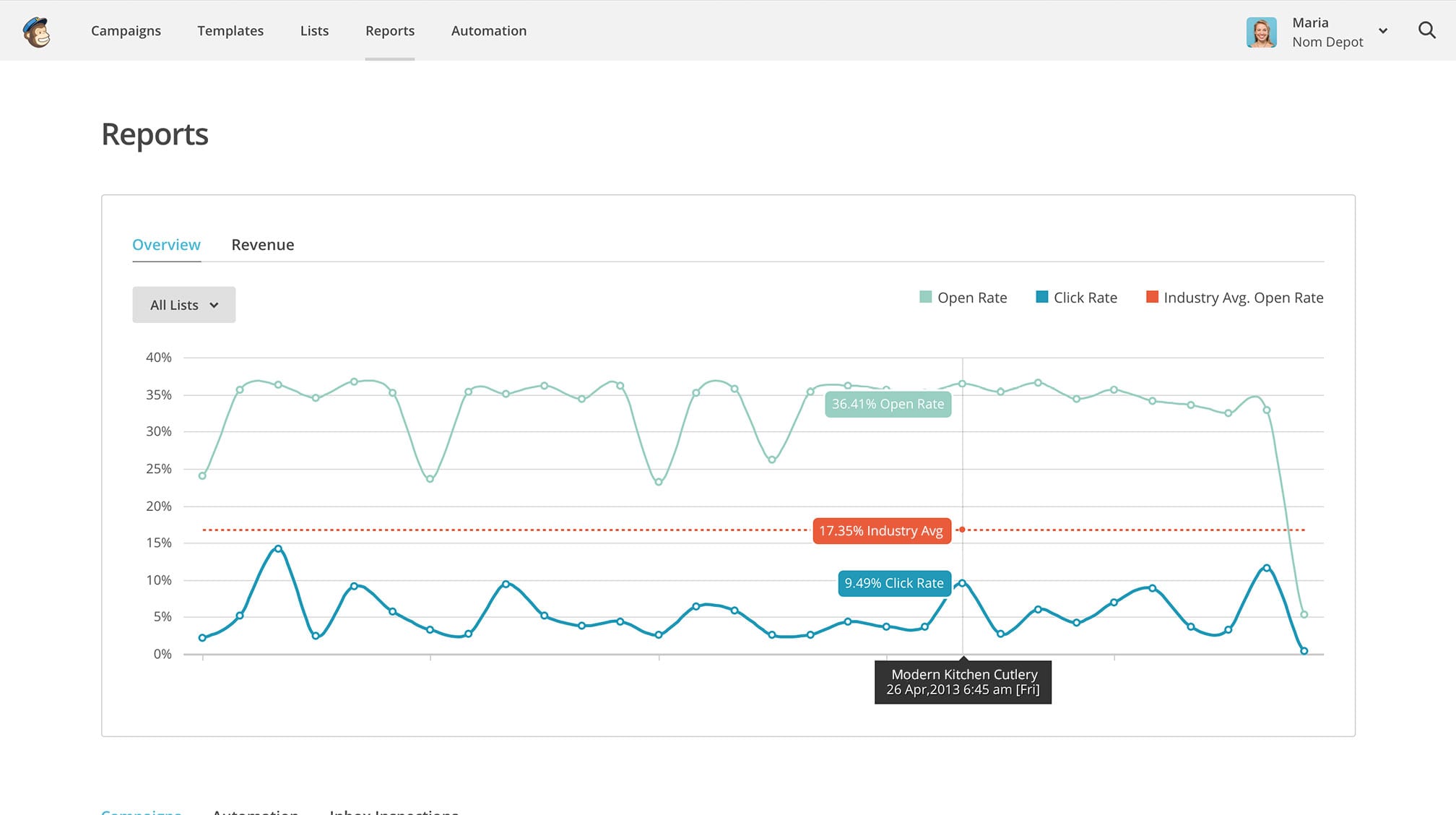

Don’t let Mail Chimp’s links to funny YouTube clips or humorous messages throw you off. It’s all business when it comes to collecting statistics, sending emails and improving performance.

You can even send out surveys. This is a great opportunity for subscribers to vote on the best icon for your app.

The dashboard lays it all out clearly: import lists, create and send campaigns, and proceed to build your audience.

As the import happens in the background, you can work on building your campaign. You have the option to choose if everyone in your list gets the email or a specific segment only – the process is very customizable.

Creating a segment is simple, use filters to build contacts subsets, use previously created segments or cut/paste from a recipient email address list. The tracking options let you know who has opened the email messages and which campaign links receives the most clicks.

The enhanced tracking option links to your website through Salesforce or Google Analytics. To use “auto-responders”, you must have a paid account – you can automatically trigger specific responses or segment users based on actions they take. After sending out your emails, MailChimp allows you to integrate your social channels to post regular updates on Twitter and Facebook.

Pricing:

MailChimp offers free subscription for 2000 subscribers or 12,000 emails per month. For unlimited account, the pricing starts from $10.

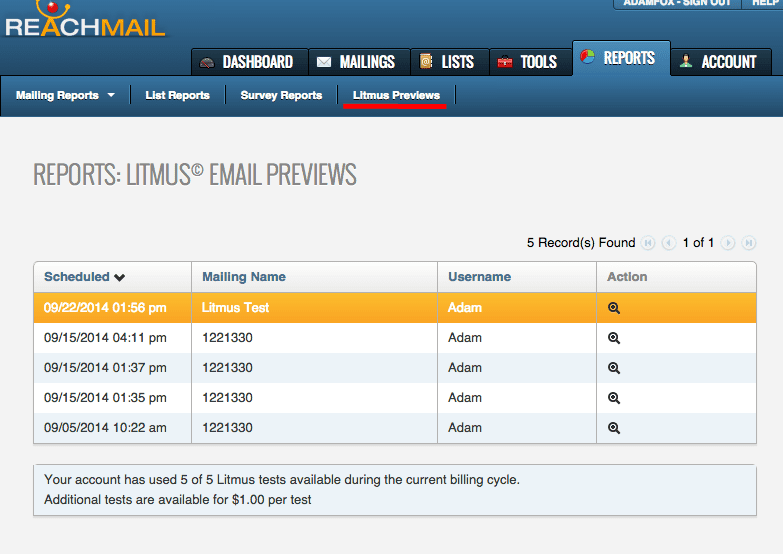

Reach Mail

Use Reach Mail’s Message Testing feature to see a direct performance metrics comparison of as many as five individual email campaigns. This feature also takes into account different subject lines or content within each email, so you can optimize the subject line wording or determine how any given email performs in contrast to others.

Through this feature, you can also decide on the percentage of your subscriber list that should be used to test the message. Once the ‘test campaign’ has finished, the system will generate a snapshot report highlighting open and click rates for each version. All you need to do is select the best-performing one and schedule the rest of your emails.

Reach Mail also gives you the option to choose from several hundred email templates or let one of their designers custom-design it for you.

Advanced tracking lets you see who clicked on your links, how many users forwarded your message or who opted out. From there on, you can send a follow-up email campaign to the users how clicked on specific links.

Pricing:

Reach Mail starts from $10 per month to $70/month.

Target Hero

Target Hero has a prominent WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) editor, image hosting, HTML as well as plain text emails, and a host of features you’d want to have in email marketing software.

This tool is ideal for businesses that require a wide spectrum of features to run their campaigns, but often lack the large subscriber lists.

Target Hero requires account verification, to do this, you’ll have to sign up, then follow the SMS authentication process.

Pricing:

Their free plan gives you 1,000 contacts with unlimited emails. For up to 3,000 contacts, you need to get the $9.90/month Mini Hero plan. The Hero plan gives you as many as 5,000 contacts at $19.90. And, the Super Hero plan can be had for $39.90 for up to 10,000 contacts.

Drip

Drip is a versatile email marketing platform which encompasses a number of useful features, including message personalization, integration with e-commerce platforms including Shopify, comprehensive data analytics and much more.

It supports a pair of distinct tools for building emails; one visual, the other text-based. This helps create impactful image-driven marketing, alongside follow-up messages that are more targeted and personal to individual users.

Customising content is straightforward, so emails will always feel relevant to those that receive them. There’s even a bespoke conversion tracking feature that puts businesses in control of how the performance and effectiveness of an email marketing campaign is assessed.

Pricing:

The Drip starter package is free to use, accommodating up to 100 subscribers without costing a penny. The Basic package starts at $41 for up to 2500 subscribers, the Pro costs $83 monthly for 5000 subscribers, and the Enterprise package has a variable cost according to the number of subscribers over this limit.

Mad Mimi

Create professional-grade emails with Mad Mimi’s straightforward WYSIWG editor. Choose from 39 social networking buttons like share, like, pin and retweet and easily customize your emails to add links.

Aside from creating fresh email marketing campaigns, you can copy campaigns using the clone tool – adjust the original document without making changes to prior versions of your work. For the accident-prone among us, there’s no need to worry about deleting your email campaigns as you can always undo the deletion. Phew!

The detailed reporting features allow you to see how many emails were opened, number of embedded links, how many shares there were on social media and a lot more. You can also find out about the links any particular user clicks on.

Mad Mimi integrates with Google Analytics to provide in-depth statistics and click tracking. Get “forward to friend” reports and export them to Excel if you wish. View real-time responses on your social networking activity with regard to email campaigns.

Pricing:

Mad Mimi pricing starts from $10 per month basic account for 500 contacts and the pro package costs $42 for 10,000 contacts.

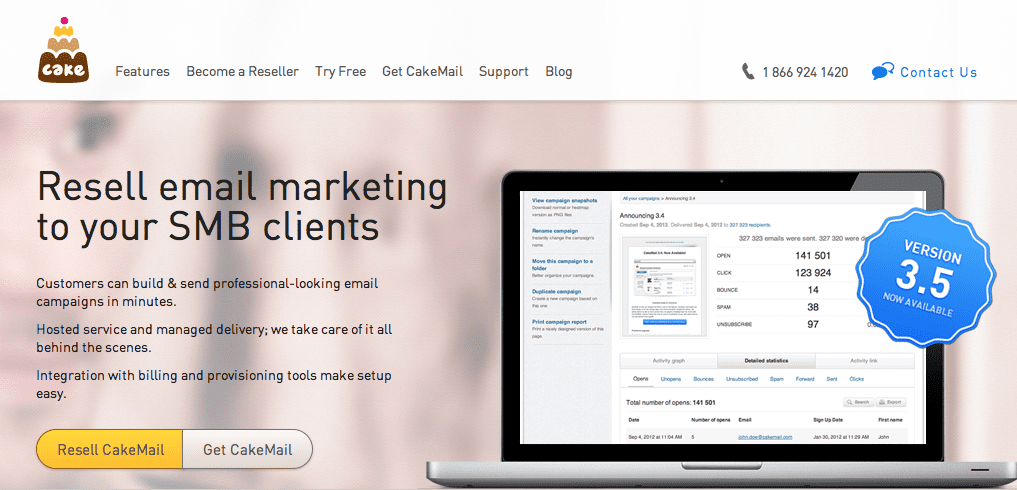

Cake Mail

CakeMail’s tools have your email campaign covered. One great feature is split A/B testing for example, to help determine the most ideal mailing list or Spam Assassin to make sure your emails don’t end up in spam. There’s Google Integration as well to let you view detailed stats on how each campaign is faring.

Sending out emails is a seamless process. Just give your campaign a title, set your recipients, design your email and choose the time to send. Pick from twenty default templates with fully customizable options or upload your own. HTML-savvy users are going to be pleased with the advanced editing option. The editor also lets you add, delete, and rearrange sections of your email like text boxes, images, QR codes, social media elements, and Google Maps.

The Campaign Analysis Tools use Google Analytics to give detailed reports on open, click, bounce and unsubscribe rates for your contacts. Use this information to group contacts into lists depending on email patterns and user interests.

Pricing:

The free Starter plan allows 500 contacts along with 500 emails. The basic package starts from $8 per month.

Mailjet

Use Mailjet to conveniently combine template-based marketing and transactional email sending in one online app. Add to that a consultation service to boot, and you’re all set.

The SMTP server and RESTful API integrate smoothly with the rest of your apps. Libraries let you add Mailjet support to your app in several languages, including Python, Ruby and PHP, and integrations with Magento, WordPress and much more. You never have to worry about getting stuck either, as there’s a 24-hour support line.

Take advantage of the email template designer or upload your own. There are also tools to segments lists and personalize emails with all your contact data. The A/X testing feature allows you to test up to ten different versions of your email before you decide which one stands out as the best. A campaign comparison tool pits your previous campaigns against the current one to give a complete picture.

Manage email lists, stats and templates all inside Mailjet’s interface, but eventually, you get to decide how you want them sent. For example, you can use the app’s UUI to create a campaign or you could use the API integration and use a few lines of code to launch a formatted email campaign to your contacts.

Pricing:

The free plan bags you 100,000 contacts and you get to send 6,000 emails a month. The bronze package costs you around $7.49/month.

Flashissue

Flashissue is one of the best tools for emailing newsletters. A simple interface combines email marketing with content curation. Sign in through Google or Facebook and have newsletters emailed to your contacts in just five minutes.

No matter what the focus of your newsletter is, you can pull down content from blog posts or search the web to pull content from a variety of sources – Flashissue automatically summarizes this content for you. After populating the editor with a certain number of story summaries, you can change the headline and article descriptions in order to better personalize it for your readers. This allows a more tailored emailer, rather than just generic news.

After this, you need to upload a banner and decide on the best way of delivering it. Even the free version boasts plenty of functionality – you can send your newsletter either through Flashissue itself or Gmail, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Google+ and a variety of other platforms as well.

Get a premium account which ranges between $20 and $50, and Flashissue integrates with Constant Contact and MailChimp to unlock a host of extra features.

Pricing:

The free Solo plan gives you 25 contacts a month with unlimited emails and group plan starts from $5 per month with 250 contacts.

Constant Contact

Scroll through several hundred design templates or custom design your own. Insert a wide assortment of extra features if you wish – documents, images, polls, links to surveys, videos etc.

Images and text can also be imported directly into the WYSIWYG editor. Create comprehensive reports on your email campaigns to show number of opt-outs, complaints, bounces, forwards and click-throughs. The social-share toolbar and social media buttons – Twitter, LinkedIn and Facebook – will work wonders to boost traffic to your web page.

Pricing:

They offer two plans; the email plan starts at $20 per month and the email plus plan starts at $45 per month.

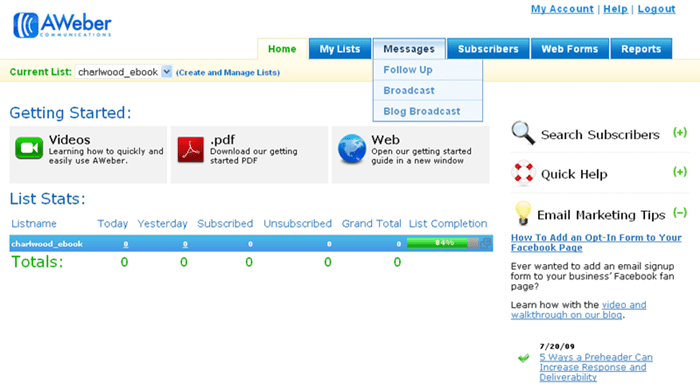

AWeber

AWeber’s autoresponder tool is a great way to engage your customers. You get access to over 150 email templates to make the email design process hiccup-free.

Improve various business functions by integrating your email marketing account with other online services. If you happen to be using a service like Salesforce, you can customize your account to automatically display which customers are subscribed to AWeber emails, and the emails they’ve gotten from you.

Your AWeber account can also integrate with the most well-known shopping cart tools, letting you add new customers each time they make a purchase on your website. If you want to take your marketing efforts to the next level, you can visit AWeber Labs to build your own apps and time-saving tools through the AWeber API. With this kind of flexibility at your fingertips, you can really take advantage of customer data in order to better optimize marketing strategies.

Pricing:

AWeber’s monthly plan goes for $19 and provides 500 subscribers, unlimited emails and a 30-day money back guarantee.

iContact

iContact’s package is simple yet intuititve – it comes complete with HTML coding options and marketing templates, depending on how deep you want to get into your campaign.

An easy-to-navigate interface greets you and the tabs at the top half of the screen let you create email campaigns and see how they’re performing. After choosing a tab, leave it up to the setup wizard to guide you through the rest of the process.

Once you have a list of contacts, iContact helps you add a sign-up form to your website so you can convert visitors to solidified subscribers. Got a list of subscribers saved in a CSV or Excel file? Import them into your iContact subscriber list.

Create aliases and send out emails according to specific filters to define your target market. iContact also embraces social media and integrates Twitter as well as Facebook-friendly features.

The autoresponder feature sends automatic messages at preset intervals which are triggered by certain events. For instance, if a newsletter is signed up for, the autoresponder sends that person a short welcome message. Or, when a customer’s birthday is coming up, you could send them email coupons.

Pricing:

iContact has special packages for Small businesses starts from $14 to $117 monthly.

GetResponse

Effectively maintain your contacts list and create professional-grade marketing campaigns.

The contacts section lets you add custom fields to contact lists and allows you to copy contacts as well as conduct searches.

GetResponse will track how many subscribers view your emails, complain, unsubscribe or click on links. You will also know how many emails failed to arrive at their destination due to any given reason. You can also find out why people unsubscribed.

Clearly labeled data is displayed in pie charts and bar graphs. You can view a summary of results after sending out surveys.

Help and support comes in the form of FAQS, webinars, PDFs, video tutorials, a glossary and learning center articles. There’s email and chat support.

Pricing:

They offer various packages depends on the number of subscribers, the basic starts from $15 per month with 1,000 subscribers.

Zoho

Zoho’s campaign process is divided into three sections: Basic Details where you select the campaign’s name and email details, Content and, The Audience. The last two are self-explanatory.

Your campaign can be completed once you select your recipients and other campaign-specific details. In the Content section, you’ll find an incredibly useful WYSIWYG editor used for HTML content. Add images, drag and drop items, format text and copy/paste any text you want in your email. Want this layout and format to be used by default for every campaign? Save to Library and you’re covered.

Take advantage of user-defined tags by creating user-defined fields. Once you create a new field, you can create more powerful custom tags. The kind of custom fields and tags you create is governed by the type of products and servicing you’re offering.

Pricing:

The free test plan unlocks 2,000 subscribers/12,000 emails a month. Pricing starts with $5/month.

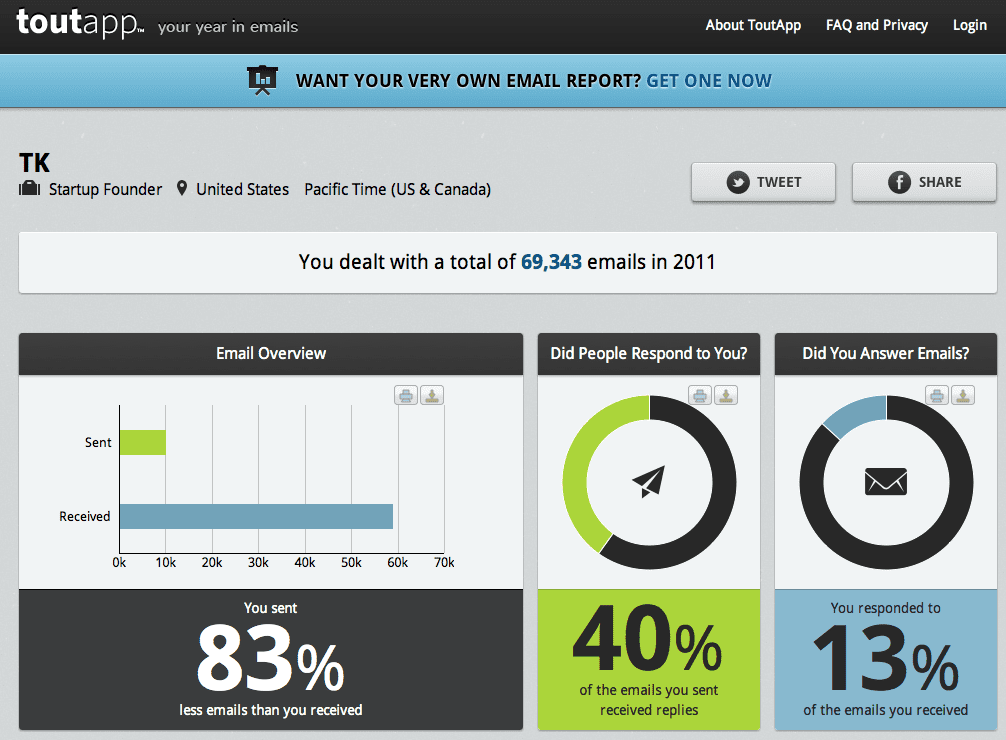

ToutApp

When it comes to functionality and features, ToutApp has found its place as the Swiss Army Knife of email marketing tools.

The need for your sales team to be equipped with templates is always there – in this department, ToutApp excels. You also need visibility into what emails got delivered, which ones were opened or forwarded, in addition to links clicked, attachments opened and attached PDF pages that were opened.

Mobile access allows all features to be easily accessed from your smartphone. Use scheduling to determine which batch of emails go out when.

ToutApp includes CRM integration and analytics. This gives you full transparency to know exactly how your emails are doing at any given stage of the process.

The desktop alert and notification lets you know who opened and forwarded emails, and to top it all off, there’s an email chat feature that lets you contact support right through the email you send them. Simply cool.

Pricing:

They offers a free 14 day trial account and the basic package starts at $30/month.

LeadPages

You can create superb landing pages with ease using LeadPages, and the best part is you don’t need to get into your tech-nerd shoes just to make the most of it.

Create a variety of landing pages for your site – pages that ar necessary for having a prominent online presence without having to use an advanced code.

The editing template offers plenty of flexibility to customize landing pages whenever needed – 50 templates to be exact. Loading time on the site is a breeze, courtesy of easily readable code.

There’s seamless integration with the best email marketing providers. You’re only a few clicks away from integrating your landing page with the desired marketing platform.

Pricing:

They have multiple monthly and annual plans; the basic package starts from $25/month.

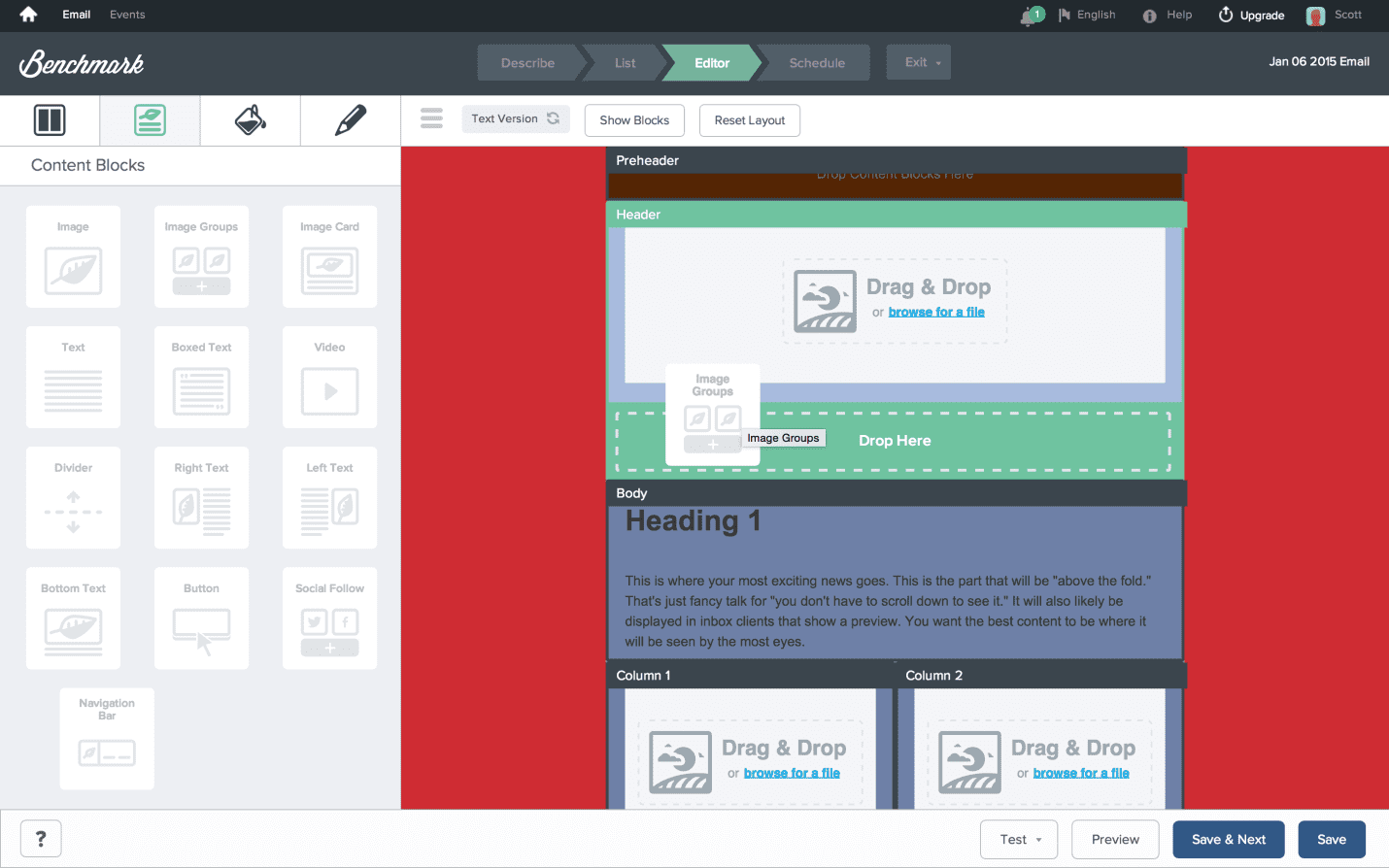

BenchMark

This tool provides multiple templates for almost every purpose, including; newsletter, greetings, promotion templates, giveaways, etc. With the intuitive visual editor tool, you can add your own HTML and CSS to give more personalized look. With the built in spam filter, you can cross check your template and make sure it doesn’t contain any objectionable material.

They have a brilliant community system that encourages your own personalized designs and vote your idea. If your design receives most votes, their development team look into it and add it in the next update. It just shows how seriously they value the feedback of their customers.

Pricing:

The basic package starts with 600 emails at $9.95/month to 2500 emails in $19.95 per month.

Infusionsoft

Infusionsoft can be expensive to acquire, but you’re going to be amazed by the ROI.

The average ROI of email marketing in the US is 44%. Case studies indicate people have reported more than 300% increase in profit and growing revenue nearly eight times while using Infusionsoft.

Simply go through the purchase and setup process, followed by the Kickstarter session and finally, setting up your automated marketing campaigns.

The flowchart-style campaign will win you over in a heartbeat. Building email campaigns is pure fun and it is indeed a satisfying feeling to know that at any time, all your customers are being given attention and interacted with in a highly personalized way, while you focus on other priorities.

The CRM’s lead scoring feature is a real standout, though nothing extraordinary, but still generally better and more adept than most CRM platforms.

Pricing:

The basis package starts from $199/month with 2,500 contacts and up to 12,500 emails.

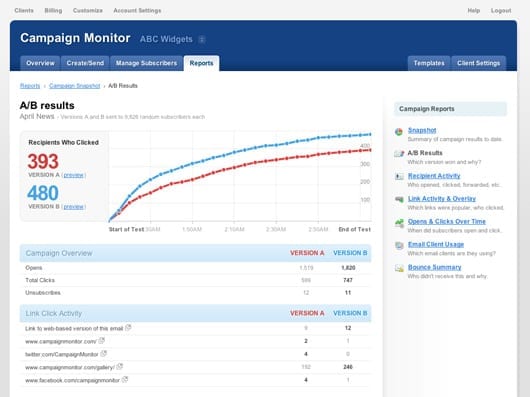

Campaign Monitor

The Template Builder tool ensures that all emails can be easily read on a mobile device in order to curb the possibility of missed opportunities due to emails displaying improperly.

Campaign Monitor generates actual screens of your email design in popular email clients like Gmail, Hotmail, Yahoo and many more. This allows you to get your campaigns displaying properly in all email clients.

Import your own HTML templates by using Campaign Monitor’s tags to make sure you’re able to use its integrated template editor to edit and personalize content in future. A variety of formats can be uploaded including Excel, tab delimited and CSV, you can also copy/paste content directly.

Setting autoresponders is fairly easy and you can use data segmentation to make sure only the intended users receive them.

One of Campaign Monitor’s key strengths is the interface. It’s absolutely clutter-free and straight-forward.

Pricing:

They have two packages; basic one starts from $9 per month and the unlimited costs $29/month.

Crystal

Crystal is a communication tool that enhances your emails by telling you anyone’s personality. Using Personality AI, a new technology that employs machine learning and artificial intelligence to predict personality based on someone’s online footprint, Crystal can help you better understand your audience, increase your open and response rates, and see higher conversion.

Using Crystal’s AI email guidance, you can see the most effective writing style, subject line, greeting and call to action to make each message most impactful for the recipient. The best part is you can predict personalities in bulk so you can send hyper-personalized emails en masse, giving your recipients the information they need in the style they want, which will benefit engagement rates, in return. It’s like having a coach for every campaign.

Pricing:

Crystal pricing plans start at $29/mo for their premium tools.

Omnisend

Omnisend is the tool you go for when you want to go further than basic email marketing. This platform allows you to create sophisticated automation workflows in minutes using pre-built customizable templates.

But what really sets Omnisend apart from the others is that you can add several channels to the same workflow. Supporting channels such as email, SMS, Facebook Messenger, push notifications, WhatsApp and more, you can reach your perfect customer at the perfect time on the perfect channel.

Omnisend also offers smart segmentation that allows you to layer targeting rules so you can really personalize the message you send to your customers. This means that you can go further than using their first name as personalization, and actually define what kind of message they’ll get at each moment of their customer journey.

Pricing:

Omnisend offers a free plan for basic email marketing which includes up to 2000 emails per day. For automation and more advanced features, the Standard plan starts at just $16 per month.

YesWare

Similar to ToutApp, YesWare is focused at sales teams who need to send mass personalized messages to people while also keeping track of follow ups and behavior (opens, clicks, etc).

YesWare excels at campaign and messaging tests on a smaller level than ToutApp. If your sales team needs to run a 20 – 50 person campaign with personalization and wants to save time, YesWare is a great fit. It will give them visibility into what happened after they pressed the send buttons.

Through YesWare’s dashboard you’ll be able to see who opened, clicked, forwarded or replied to the emails sent out. In addition YesWare offers template-based analytics to understand what is working and what isn’t.

Similar to ToutApp, YesWare integrates to most popular CRM solutions in order to give you transparency into what your sales team is doing without having to go into YesWare at all.

They also offer desktop notifications with a built-in dialer for those times when an immediate call after open is necessary to close the deal.

Pricing:

They offer a 30 day Enterprise trial, after which they start at $12/user/month and go up to $55/user/month.

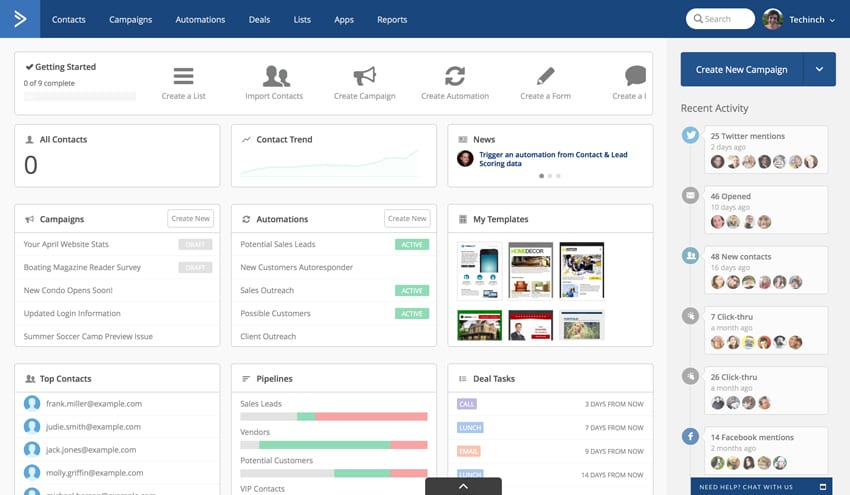

ActiveCampaign

ActiveCampaign has been called one of the key InfusionSoft alternatives. For those who want the robust sales and marketing automation power of InfusionSoft, but easier to use and setup, there’s ActiveCampaign.

Despite the lower cost and ease of use compared to InfusionSoft, you aren’t losing a lot in terms of functionality. ActiveCampaign still allows you to run very behaviorally driven marketing and sales campaigns, but with a setup that most somewhat tech-savvy business owners can actually understand.

The full-blown version of ActiveCampaign offers an all-in-one solution for a business to house it’s CRM, email marketing, deal flow, sales automation and more. With the offer of one-on-one training and onboarding, without the 4-figure fee that InfusionSoft requires, it’s a great alternative if you want to automate the way you keep in touch with your customers both new and old.

Pricing:

ActiveCampaign starts at $7.65/month if paid annually and goes up to $149/month for the full blown package.

Voila Norbert:

Voila Norbert offers two great services for small businesses, email finding and email verifying. Their email finding tool was elected the most accurate email finder out there according to ahrefs. Whether you’re trying to reach out to influencers, build marketing connections or reach potential recruits, Norbert’s got you covered.

Maintaining a clean email list is crucial to ensure high deliverability and a good sender score. With voila norbers email verification tool it cleans your entire list for you in a matter of minutes.

Pricing:

They offer 50 free credits for the email finding service to test it out. Thereafter the pricing works out on a tiered basis depending on your needs. The verifying pricing works out at around $0.003 an email in bulk.

Did We Miss Anything?

Is there any tool I missed out? I’m sure, I did.. Tell us in the comments section and do let us know what do you think about the above ones. I’m always interested in hearing suggestions or new ideas.