It’s high time you integrate geofencing into your business. It’s proven to get you more sales, engagement, and loyal customers.

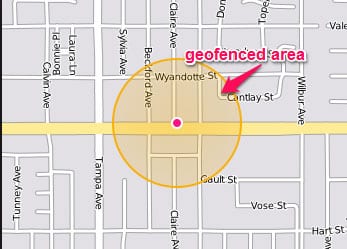

Geofencing is a location-based service that businesses use to engage their audience by sending relevant messages to smartphone users who enter a pre-defined location or geographic area.

There are smart companies that send product offers or specific promotions to consumers’ smartphones when they trigger a search in a particular geographic location, enter a mall, neighborhood, or store.

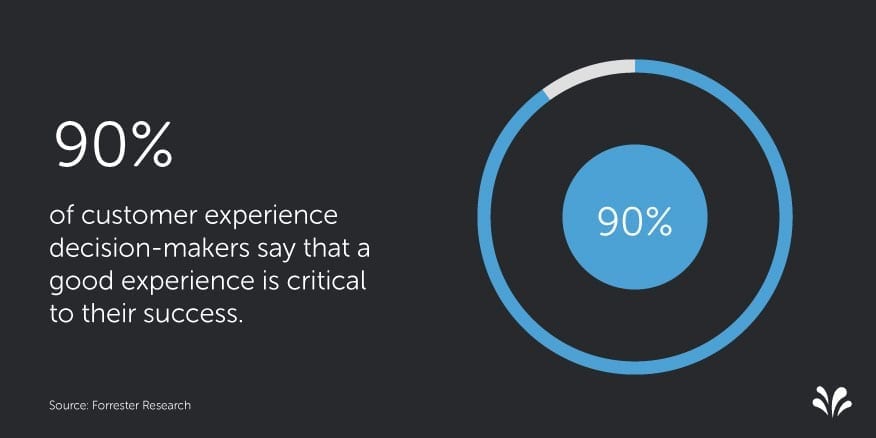

Do you desire to improve your customer experience? I’m sure you are, considering that 90% of customer experience decision-makers have agreed that a good customer experience is critical for their success.

And with customers being the major source of revenue for every business, delivering high-quality service through geofencing is important. If you’re into any form of digital marketing, you need to take this seriously as it’d help you acquire new customers and convert them into paying customers.

A Study by Bain & Company shows that a little increase of 5% in customer retention, can lead to a profit increase of 25% to 95%. Trust me, these numbers are worth paying attention to!

Since customer retention is too challenging, knowing how to interact with your potential leads in a more personalized manner will definitely help.

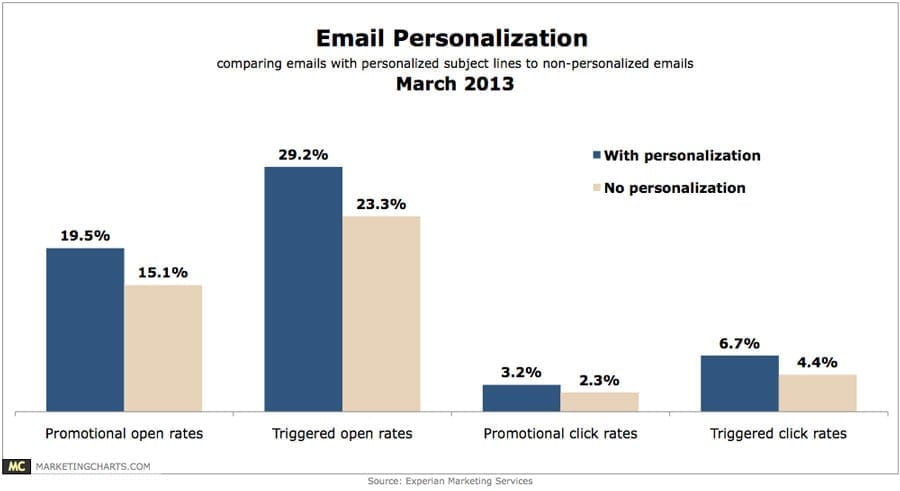

A research report by Experian shows that personalized emails sent to consumers have a great effect on open rate, triggered open rate, promotional click rates, and triggered click rates.

So, the earlier you start reaching out to potential and loyal consumers at the most relevant time, with the relevant product/service, the better the results you’re likely to get.

So how do you achieve it?

Simple: Integrate “geofencing” into your marketing strategy and you’d be amazed at the consistent results that you’ll get. Creating geofencing campaigns can truly transform every facet of your business.

Does it work? Well, Papa John’s is renowned for their Super Bowl ads, but they ran a mobile ad triggered by Geofencing solutions from ThumbVista, to promote their Papa Loyalty Programs.

At the end of the campaign, the brand recorded over 68K impressions with 469 actions taken resulting with a .69% CTR. They also gained a brand awareness with the rewards program in a new market area.

You might have heard of it, or this could be your very first time to hear it — and I guess you’re now wondering what it’s all about.

Having been introduced to geofencing and how it can help with customer service, let’s consider a few definitions.

What is Geofencing?

According to Techopedia, geofencing is described as:

“A technology that defines a virtual boundary around a real-world geographical area.”

While Wikipedia defines it as:

“Virtual perimeter for a real-world geographic area.”

It’s not some complicated programming language or complex development tool.

Geofencing is a technique of serving smartphone users with ads that are relevant to them, by creating a virtual perimeter or boundary around your business location which notifies users as soon as they enter the boundary.

In other words, geofencing can be regarded as a mobile marketing optimization strategy. So far, you could see the bright side of your business as you leverage on mobile ads that are targeted to your customers within a geographic location.

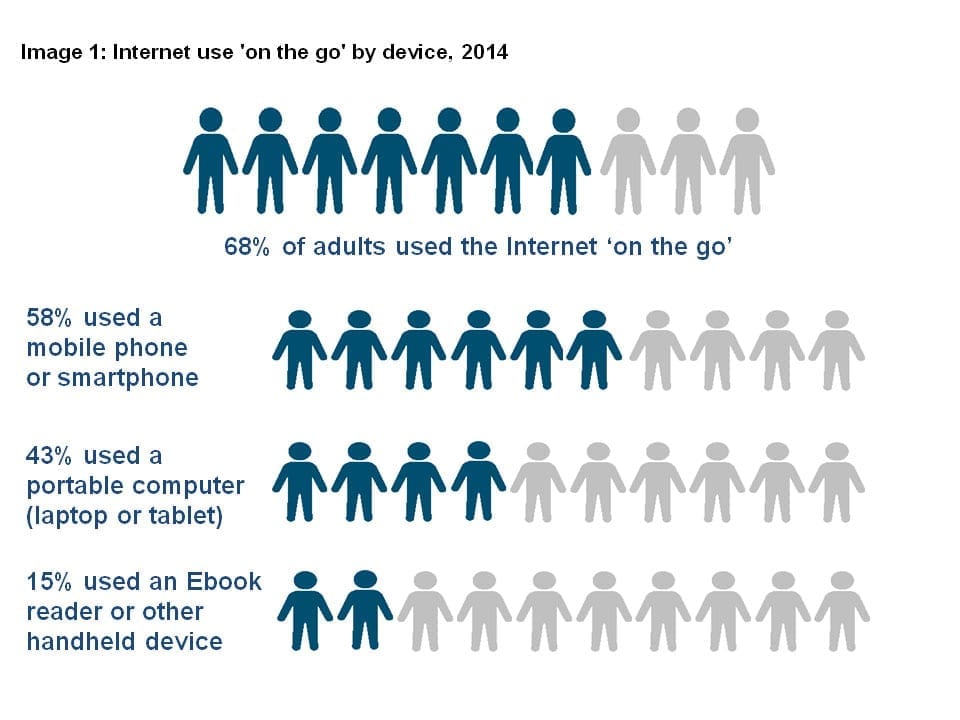

People are always ‘on the go,’ but they always have their smartphones with them — which they use to research products and services before buying them.

A report by the Office for National Statistics revealed that 58% of internet use ‘on the go’ is on mobile phones or smartphones.

For this reason, you’re no longer at a crossroad on whether you should start building geofencing campaigns or ignore it. Right now, it’s an important aspect of your marketing strategy.

Is Geofencing Right For Your Business?

Why is geofencing so important today?

You may not fully be aware, but let’s review some of the reasons that will make you kick yourself in the butt for not leveraging it:

i) Easy customer reach: When it comes to reaching out to your customers, geofencing is an option you shouldn’t neglect — because it notifies your customer about your product/services whenever they’re close to your business location through their mobile phone. That’s cool, isn’t it?

There’s no doubt as to the results it will generate, especially when you consider how addicted people are to their mobile phones.

ii) Instant consideration: Can you call the attention of your customers instantly when they walk by your store without shouting at the top of your voice?

I doubt.

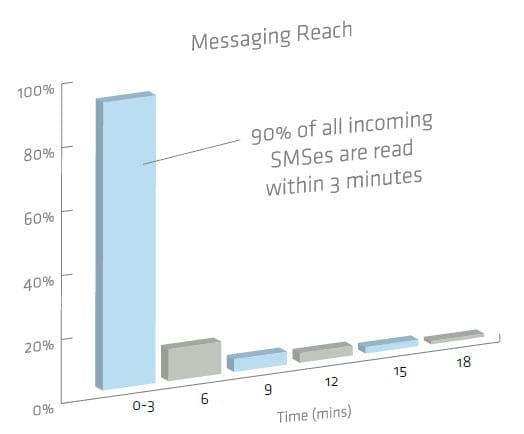

Through geofencing, you’re able to trigger instant messages that pique a customer’s interest and nudges them to come check out the latest deals in your store. Remember that 90% of SMS are read within 3 minutes — so, geofencing campaigns help consumers make informed and instant decisions.

iii) Grows brand awareness: The mobile marketing strategy that leverages on geofencing provides local and multi-channel businesses, the chance to communicate with their potential consumers who are close by and ready to purchase through mobile phones.

These messages serve as a reminder to your consumers to choose your brand out of the thousands of other similar businesses around a particular location.

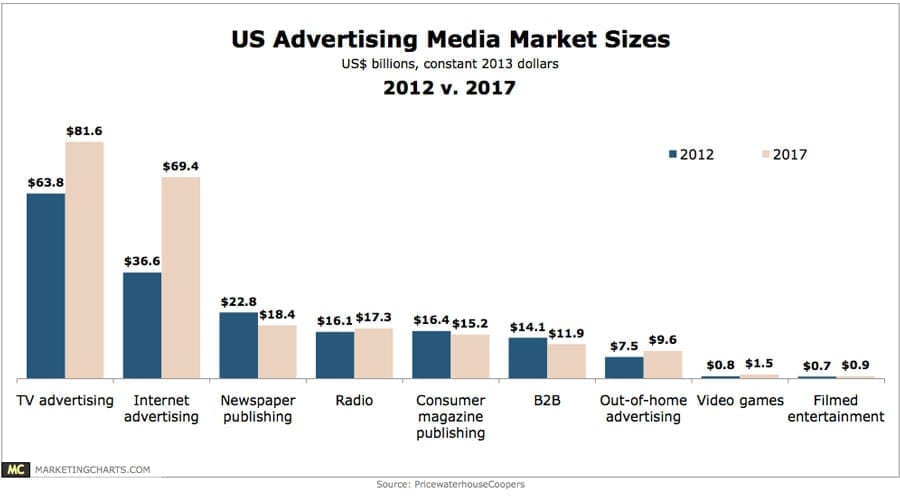

iv) Reduction in cost of marketing: With the high cost of creating ads campaign, using geofencing is sure to cut down the cost and still produce a great result — since it only focuses on local consumers and these consumers are likely to buy from you.

Geofencing is more like an extension of your restaurant, store or shop. And with geofencing you don’t need to stand in front of your store to call anybody that passes by, because you’ve already known your potential consumers.

You’re also provided with the opportunity to offer your products/services to your customers at the right time when they’re in need of it.

With the availability of GPS on virtually all smartphones and tablets, efficient tracking is now easier for both marketers and consumers.

This new development has also given rise to new marketing opportunities for online entrepreneurs, because they can now locate their potential consumers right on the go.

A lot of brands have recorded success through their geofencing campaigns — especially those with highly classified data that need utmost security.

Here are some of the business models or organisations that can make use geofencing application:

i) Asset management: The application will notify a network administrator when a company asset, meant to be used within the firm goes out. And from there, they can track the location and also lock it from being accessed.

ii) Fleet management: In this field, geofencing is used to notify a dispatcher when their vehicle goes out from its route.

iii) Human resource management: Here geofencing is used to restrict staff from having access to some spaces within the firm, without a second authentication.

iv) Drone management: It’s used to create a temporary restricted area for drones, during a sporting event.

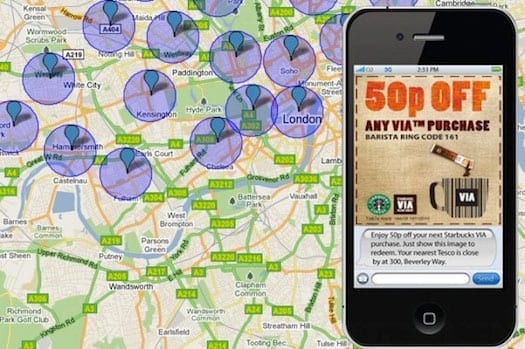

v) Marketing: A brand can use geofencing to notify their customers of their coupons, new product, or ongoing promo when the consumer enters a specified geographical region with their mobile phone.

vi) Law enforcement: In this instance, geofencing can help the security authority when a person under house arrest goes out from the building.

How Does Geofencing Work?

So far, we’ve covered a lot about geofencing and what it can do for your business. Do you know how it works?

It’s simple though. Geofencing helps you to keep in control of your business by notifying you when a potential consumer is passing by your store, by a competitor’s, or entering into a predefined area.

To get it working, you need to use a mapping product like Google Map to map out the regions you want to geofence. This region can be in a circular or polygon shape in most cases.

Once your desired region is mapped out for geofencing, you can then target your consumers via their mobile phone’s GPS.

Then, you can monitor your geofence through the day for potential prospects or customers who might be interested in your offer. It keeps to track them until that parameter is breached — either they’re trying to enter or to go out.

In fact, for a successful geofencing to be attained, you also need to incorporate a definite customer targeting, and personalized messages.

Solely depending on technology is not effective.

Benefits Of Geofencing

The need to leverage on geofencing cannot be overemphasized. Though it’s still a new practice, but the rate of success achieved with it is immeasurable.

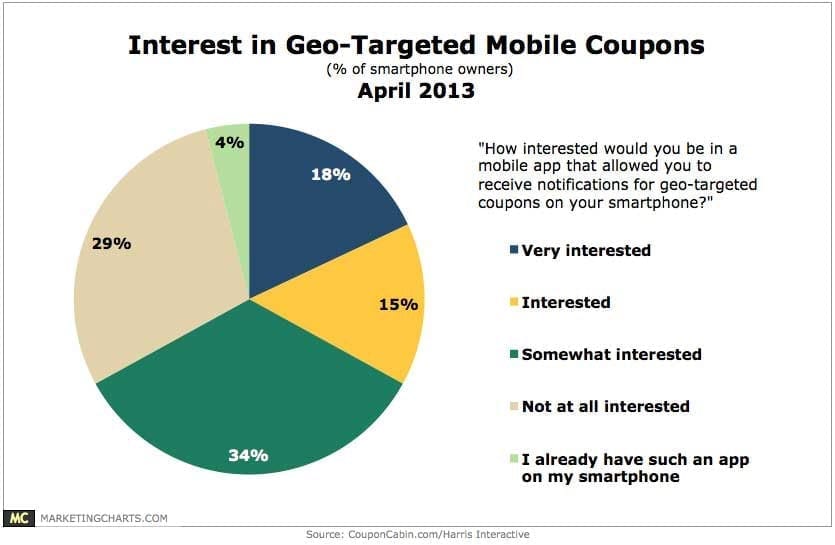

A study shows that consumers love receiving location-specific offers right on their phone, due to its location relevance and interest.

That said, here are some benefits you wouldn’t like to miss:

i) It serves as an ads portal: This is obtained when potential consumers are close to your store and you’re notified of their presence. Sending your new products to them, free giveaways and discounts, will definitely get them to consider your store.

ii) It targets your potential consumers: Social media has a bigger marketing opportunity since it’s populated with a lot of consumers that are ready to read your messages and stick to your brand.

But with the help of geofencing, you can focus your campaign to the user that are more likely to convert — especially those local consumers.

Interestingly, these are the consumers that will be excited to walk into your store and make a purchase after seeing your ads.

iii) It links your offline business to your online presence: With geofencing, you can notify passersby to look you up on social media for better customer engagement.

In fact, it serves as your gateway to your social media and internet identity.

iv) It provides real-time analytics: No doubt, a good marketing requires a to-and-fro conversation between the customers and the marketers.

Geofencing makes it a lot easier and more effective.

Because it notifies you as soon as a consumer enters your marketing region so that you can properly prepare to receive them in your store.

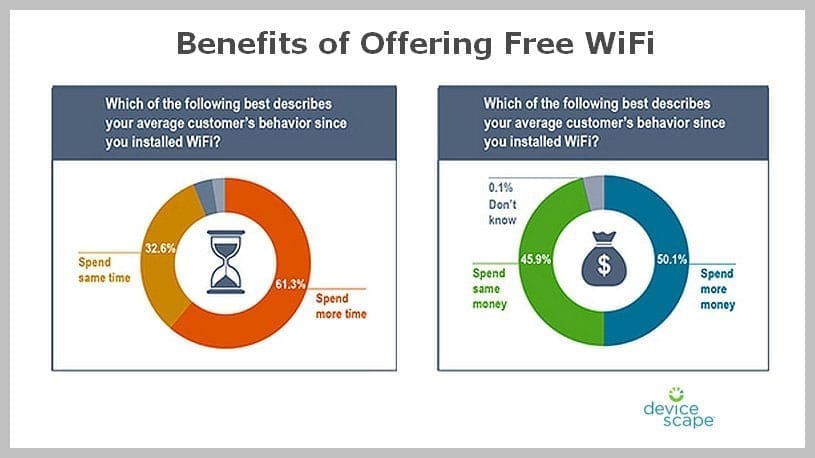

v) It offers a service: Since the mobile use rate is high and users are highly interested when they’re online, offering a free WiFi in your Restaurant, Bar, and Hospital will definitely improve customer experience.

This can be achieved by simply sending messages to passersby via geofencing, and notifying them of the free WiFi they can enjoy while in your place.

And don’t forget this has its benefits.

vi) It secures your products: Since you can keep track of people’s location with geofencing, it can also be used for tracking your employees and products.

With this technology, you get notified when an employee leaves his/her duty post or when a product is illegally removed.

Case Studies From Companies Using Geofencing

The use of geofencing is gradually becoming popular, though it’s a new marketing practice. Good news is, businesses have recorded lots of success with it. Let’s see:

i) Elle Magazine successfully increased sales with ‘shop now!’ mobile pop-up to connect potential buyers to selected stores, using the location-based offer. All thanks to geofencing.

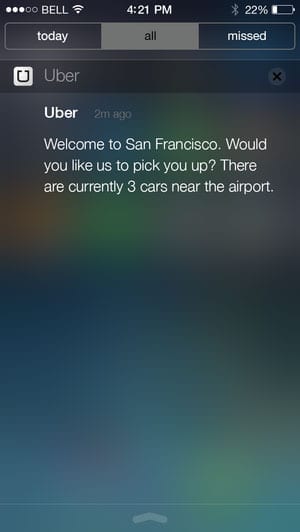

ii) Uber Car Hiring Service also used geofencing at LAX to notify people around that they can get a cab to wherever they’re going within a minute, just with a click.

iii) Wal-Mart is another brand making it real big with geofencing. Their app comes with a store mode that picks up signals when a buyer is within the store, and delivers coupons and e-receipts.

Geofencing Tools

Getting appropriate marketing tools will help you get things done on time and more efficiently. Below are some of the best tools you can use:

i) xAd: This tool eliminates every form of assumption in marketing, because it serves messages based on your potential consumer’s location.

xAd has a proprietary platform that automatically creates boundaries around places often visited by a consumer. For example, a Restaurant, Shopping mall.

It’s with these insights that marketers can target ads to their customers when they’re within those locations.

ii) Koupon Media: This tool prompts a targeted offer to shoppers when they’re within the store.

Koupon Media has features that study the behavioral attribute of buyers within the geofenced locations, and uses it to present the buyer with offers they can’t resist while they are shopping.

iii) NinthDecimal: This helps marketers to target consumers near their own stores or competitor’s locations, with tangible media ads through phone calls, appointment requests, and couponing.

It also has a walking and driving map to easily lead your customers to your nearest sales point.

In Conclusion

“In today’s modern world, people are either asleep or connected.”

– Janice H. Reinold said.

Your customers are attached to their mobile phones all the time. It’s your responsibility to engage these customers when they’re not asleep.