UX design has become one of the hottest buzzwords in the world of mobile app and web design. Yet so few design teams actually understand what it means and how to apply it properly.

Whether you’re a prospective UX designer, entrepreneur, or business user that wants to create a mobile app, this guide is perfect for you.

We’ll dive deep into the core UX design principles that must be applied to ensure your app is a success.

What is UX Design?

User experience (UX) design is the process of creating products that deliver meaningful and relevant experiences to end-users. It encompasses all stages of acquiring and integrating the project, including usability, branding, and functionality.

UX design is commonly associated with software, mobile apps, and web design. But these concepts can be applied to any product, system, or service. For example, whether you’re creating a can opener, web page, or an employee onboarding process, ease of use and enhanced user experience are important for all three.

For our purposes in this guide, we’re going to focus more on UX design as it applies to mobile apps.

Why is UX Design Important?

UX design principles provide the strong foundation that’s required to make all of the creative elements associated with your project. This includes everything from design patterns to interaction models, wireframes, storyboards, prototypes, and more.

As the name implies, UX (user experience) design focuses on the user and the user’s experience. But many designers find this definition to be a bit vague and unhelpful when they’re going through the design process.

That’s where the UX design principles come into play. If you understand these principles and core design concepts through each design phase, UX design will be integrated into each step of the UX project.

Ultimately, UX design is so important because it has a direct impact on the user’s perception of your product. If the visual design is unappealing or the design usability fails, it’s going to leave users with a bad taste in their mouths. Conversely, a great UX design keeps users engaged and coming back for more—which is crucial for mobile apps.

What’s the Difference Between the UX Design Process and UI Design?

UX design is almost always associated with user interface (UI) design. These terms are often used jointly and sometimes interchangeably. But UX components and UI components are actually very different.

In a nutshell, UI design is about the technical elements that make it possible for users to interact with a product. UX design focuses more on the user’s overall experience and perception of the software.

UX design is about solving problems and addressing pain points a user might be experiencing, whereas UI design encompasses the look and feel. The former forces you to find the right UI components to complete specific actions, navigate, and use the app with ease. The latter is more of a holistic view of the design.

Both of these are really important to consider to truly understand UX design principles. For more information, you can read our complete guide on the differences between UX and UI design.

10 UX Design Principles For Mobile App Development

Now that you understand the basics of UX design, what it means, and why it’s so important, it’s time to dive deep into user experience design principles. We’ve identified and explained the top ten UX design principles that every UX designer needs to know.

1. Prioritize the User

First and foremost, you need to meet the users’ needs. A user-centric design is arguably the most key UX design principle for mobile app development.

Even in the early stages, you need to think about what users actually look for in a design. Many designers often drop the ball here because they make too many assumptions. Some design concepts might seem like a great idea to you—but you’re not the user.

There’s a big difference between what you think users will do and what they actually do.

Testing your design concepts with a user control group is the best way to validate these ideas before putting them into practice.

As designers gain more skills in their practice, they commonly step too far outside of the box. They’re more focused on impressing their colleagues and pushing design concepts to the limits. When this happens, the user experience gets lost in the shuffle, and the UX design fails.

You must find a balance between elegant designs that are combined with form and function. The user experience must be integrated into your app design at the earliest stages, or a snowball effect will push the user further and further away as the design develops over the product life cycle.

2. Be Consistent

Another core UX design principle is consistency. Users interact with other applications and software outside of what you’re building. You need to understand that there are similar UX design patterns across most of these apps, and your application needs to mimic them.

For example, when you land on a web page, there are certain things that you expect—like a menu bar at the top of the screen. Technically, a designer could put that menu bar anywhere. They could make it a diagonal menu that runs from the bottom left corner of the screen to the top right corner of the screen. But that would be inconsistent with everything a user knows about page navigation.

There’s a fine line between being creative and consistent. If you’re on the fence, it’s always best to err on the side of caution. Don’t break away from the “accepted norms” that people are used to.

That’s the first part of being consistent with your UX design. Next, you need to make sure your design is consistent across all of your touchpoints.

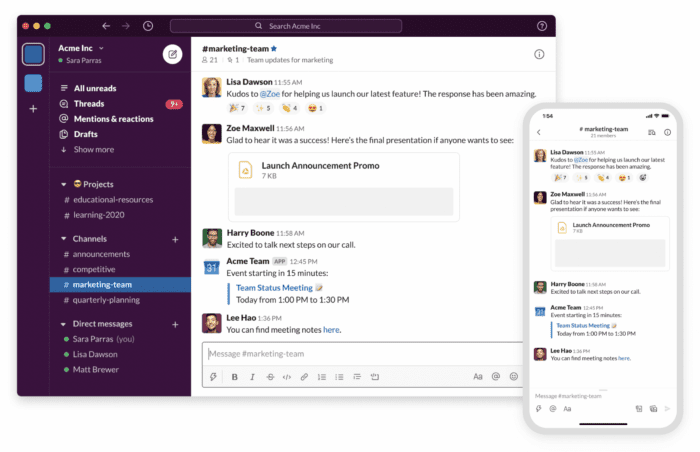

Your mobile app design, tablet app design, website design, and mobile web design should be consistent as well. Here’s an example many of you can probably relate to.

If you use Slack for business messaging, you’ll notice a consistent experience between the web version, desktop version, and mobile app version of the software.

This ensures that users have a seamless experience as they use the app across multiple devices, and they don’t need to relearn the design every time.

3. Establish a Visual Hierarchy

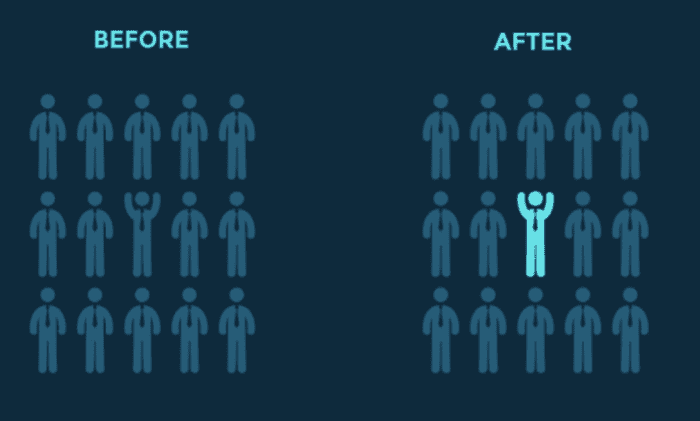

As a UX designer, you need to clearly establish a visual hierarchy on every screen. A quick glance at the page should tell users everything they need to know about what’s important and what’s not.

Bigger buttons are more important than smaller buttons. An icon that’s a different color than every other clickable icon on the screen is meant to stand out. These are the types of design patterns that you need to incorporate into your project.

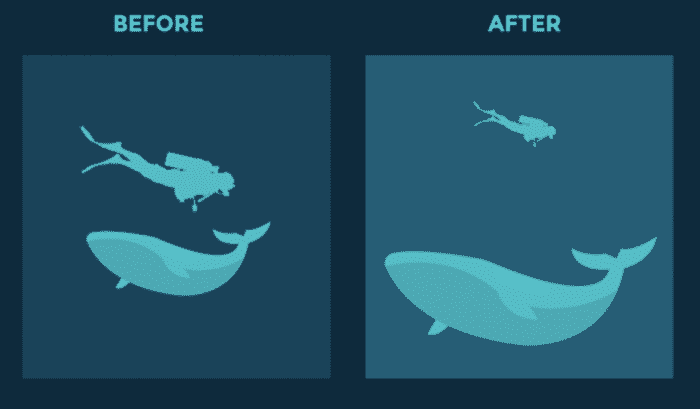

Here’s one example to showcase this point:

The image on the right establishes a visual hierarchy using both size and scale.

Applying color and contrast differences is another way to accomplish hierarchy.

Spacing, proximity, alignment, reputation, leading illness, the rule of thirds, perspective—all of these are great design tricks for UX design.

Similar to consistency, creating a hierarchy is a two-fold process. In addition to the on-screen elements, you also need to think about creating a logical navigation hierarchy.

Each internal page of the app should be no more than three clicks away from the home page.

4. Accessibility Testing

App accessibility must be taken into consideration when you’re going through the UX design process. This is for visually impaired users or anyone who might have trouble seeing things on the screen.

For example, certain colors can make it challenging for colorblind users to distinguish one button from another. Or maybe something like enabling low light settings can make it easier for someone to use the app.

Screen readers, labels, and other tools can be used to ensure nobody is hindered by the design choices.

Having a high contrast between backgrounds and other on-screen elements can also help you design for accessibility. But ultimately, you need to confirm these design choices with actual tests to ensure they meet the needs of certain users.

5. Usability Testing

As previously mentioned, lots of UX designers tend to make assumptions about their choices. But those assumptions must be validated with UX research and user testing before they get applied to the app.

This is the only way to truly see how real users interact with your mobile app.

See if your design choices hinder or impair certain in-app actions. Gather feedback about the design choices, navigation, and overall usability.

If you’ve never been through this process before, no problem. We have an in-depth guide on how to perform user testing for your app that answers all of your questions and walks you through each step.

I strongly recommend this resource as you apply this UX design principle.

6. Keep it Simple

Simplicity is another key UX design principle that’s often overlooked during the design process.

You don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Sometimes trying to be too creative and thinking too far outside of the box can do more harm than good.

Stick to what works, and don’t overcomplicate things.

A really clean, sleek, and modern design without extras is always going to be a solid choice. Try not to clutter the page or force extra elements onto each screen.

Users shouldn’t feel overwhelmed with options or choices—everything should be very straightforward and simple. This also relates back to our previous UX design principle about testing. If things aren’t simple, you should be able to quickly identify those areas when you’re running tests.

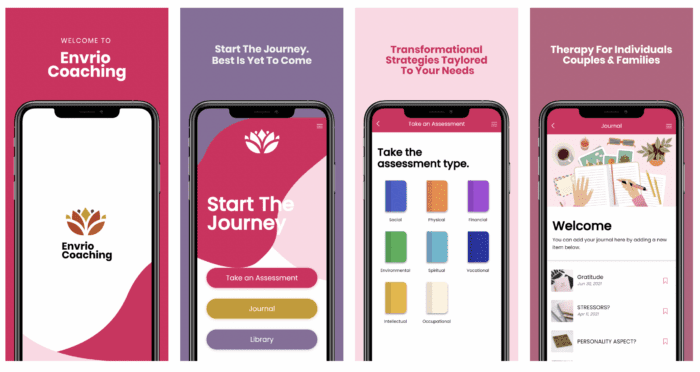

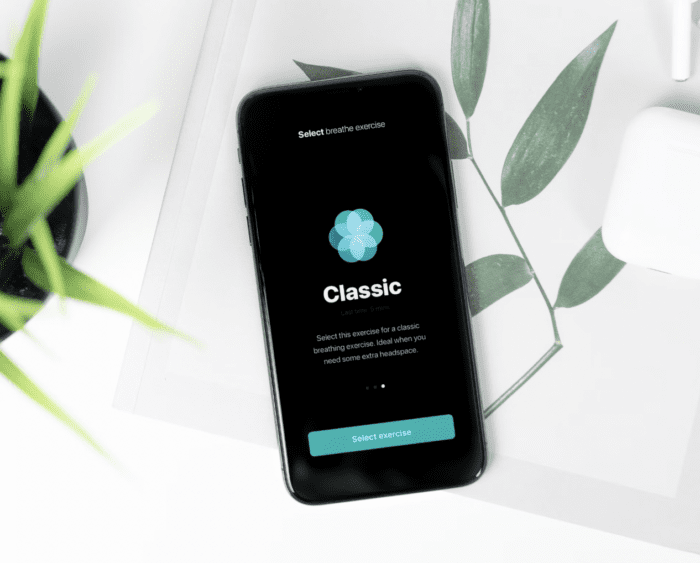

Here’s an example of a really simple and clean design:

There are no fancy bells or whistles that will distract the user from performing actions on each page and navigating throughout the app.

7. Typography

Designers don’t always think about text as part of the design language. But typography has a significant impact on the user experience and must be considered during the design process.

How will the typography seamlessly integrate with the different user interfaces of the product?

You also need to make sure the typography is consistent from screen to screen and across all of your touchpoints.

Believe it or not, your typography choices can have a major impact on the way users interpret the text and language on the screen.

In some cases, you can even integrate your typography with accessibility—a UX design principle that we discussed earlier. For example, larger text on the screen is easier to read.

This is a simple yet effective approach to applying these principles.

8. Context

It may sound like a cliché, but context is key when you’re designing anything—especially a mobile app. This is something else that many new UX designers often forget to consider in their projects.

Your design choices can impact user behavior and how users interpret the app.

For example, let’s say you were building a financial planning app. Having tons of bright colors, images of clowns, and an amusement park theme wouldn’t really be appropriate. The context is way off.

To help you with the design context, keep the following considerations in mind:

- What is the user’s goal?

- What types of tasks is the user completing?

- What type of brand image are you trying to convey?

- What are the overall organizational goals of your brand?

- What are the goals of the specific project?

- What type of environment and location will the user be in when using the app?

Apps used for personal use at home will have a different design context than professional apps used in the office.

9. Tell a Story

The best UX designers put some personality into their designs. This makes the user experience more enjoyable if it feels like there’s a user persona associated with the design.

Visual storytelling is one of the best ways to do this.

Obviously, the exact story you tell will vary based on the type of app you’re building. As mentioned, the context needs to make sense too.

But this is definitely an area where you can let your creative juices flow. Create a narrative that the user can follow as they navigate from screen to screen.

You can even use animations or create characters to tell the story for you. This is something that’s more common in gaming apps but can be applied to a wide range of potential use cases.

10. Get Confirmations

Helping users avoid mistakes is one of the most important UX design principles to consider.

For example, imagine if clicking on a product automatically facilitates a purchase in a single click. If a user accidentally clicks the wrong button, it could cost them money.

Alternatively, think of an app where the primary function is to build something important. Maybe they’re using the app to create a resume or organize their portfolio. Imagine if a single button on the screen erased all of their work.

This would obviously not lead to a positive user experience.

That’s why you need to get confirmations like “are you sure you want to delete this?” Even a simple “confirm order” button during the checkout process can get the job done.

So don’t forget these types of actions when you’re designing the app using a professional prototyping tool.

Final Thoughts — What’s the Most Important UX Design Principle?

There is no single most important UX design principle. You need to take all of these concepts into consideration when you’re designing an app.

If you need help or more inspiration, we have an entire library of design resources that you can reference. It covers everything from app design tools to branding, how-to basics, ebooks, and more.

Alternatively, you can lean on BuildFire and pass your entire design process off to the experts.

With BuildFire Plus, our team can handle all of the app design and development on your behalf. We’ll work with you on wireframes, prototypes, and mockups to ensure we’re on the same page. Then we’ll take your ideas and bring them to life.

Schedule a free consultation to learn more and get started.