With so many stages involved in an app development project, user testing is often overlooked.

But this step is crucial to the performance and success of your app. It’s something that you should be doing throughout the development process, as well as after your app has finally launched.

Overall, user testing helps eliminate problems, find bugs, and optimize the UX for your app.

Unless you’ve been through this process before, getting started with app user testing can feel like a daunting challenge. How do you conduct user testing for your app? When should you start user testing? What should you be testing? These are common questions that have probably crossed your mind.

Fortunately, you’ve come to the right place. I created this guide to explain everything you need to know about app user testing and how it works.

You’ll even find a step-by-step guide to user testing as you continue below. So regardless of your app type, industry, or experience level, this resource will steer you in the right direction for app user testing. Let’s dive in!

What is User Testing?

Before we continue, let’s start with the basics to make sure we’re all on the same page. User testing can be defined as the process of testing the interface and functions of an app, product, website, or service.

The purpose of these tests is to determine if the product in question (an app in our case) is ready for launch.

You’re essentially checking the usability of your app as real people perform specific tests in a realistic testing environment. Can your app be used naturally by a person who isn’t familiar with it? The only way to answer this question is with user testing.

As someone who has been involved throughout the development process, you can’t unbiasedly test your app’s usability on your own. Tests must be conducted by people who are neutral and don’t know how the app is supposed to work.

From a UI and UX design perspective, user testing is an absolute must. Even if you think the design and layout of your app are perfect, you’ll need to run usability tests to confirm your hypothesis.

While user testing should be conducted prior to launch, it shouldn’t stop once your app is live.

User testing is a continuous process. It’s one of the best ways to continually improve your app’s UI/UX design, especially as you come out with new updates and changes.

How to Conduct App User Testing in 6 Simple Steps

User testing isn’t really a one-size-fits-all process. But with years of experience conducting user tests, I’ve been able to narrow down the core steps to include in your testing.

Whether this is your first user test or 100th user test, the step-by-step guide outlined below will be the best way to conduct the user tests for your app. These steps are explained in a way that can be customized to fit any type of app or development project. Here’s what you need to do:

Step #1: Define Your Goals

Like any experiment, the first step to user testing is defining your goals. What exactly do you want to test? You can’t start until this question has been answered.

Your usability testing goals will change depending on where your app is in the development lifecycle. For example, some developers will run tests before the actual development phase begins. These types of tests will be centered around the discovery, exploration, and user research of your target market and what they expect in your app. Since you won’t have a functioning app yet, the goals of this type of test will look very different from a test being run just prior to an app’s launch.

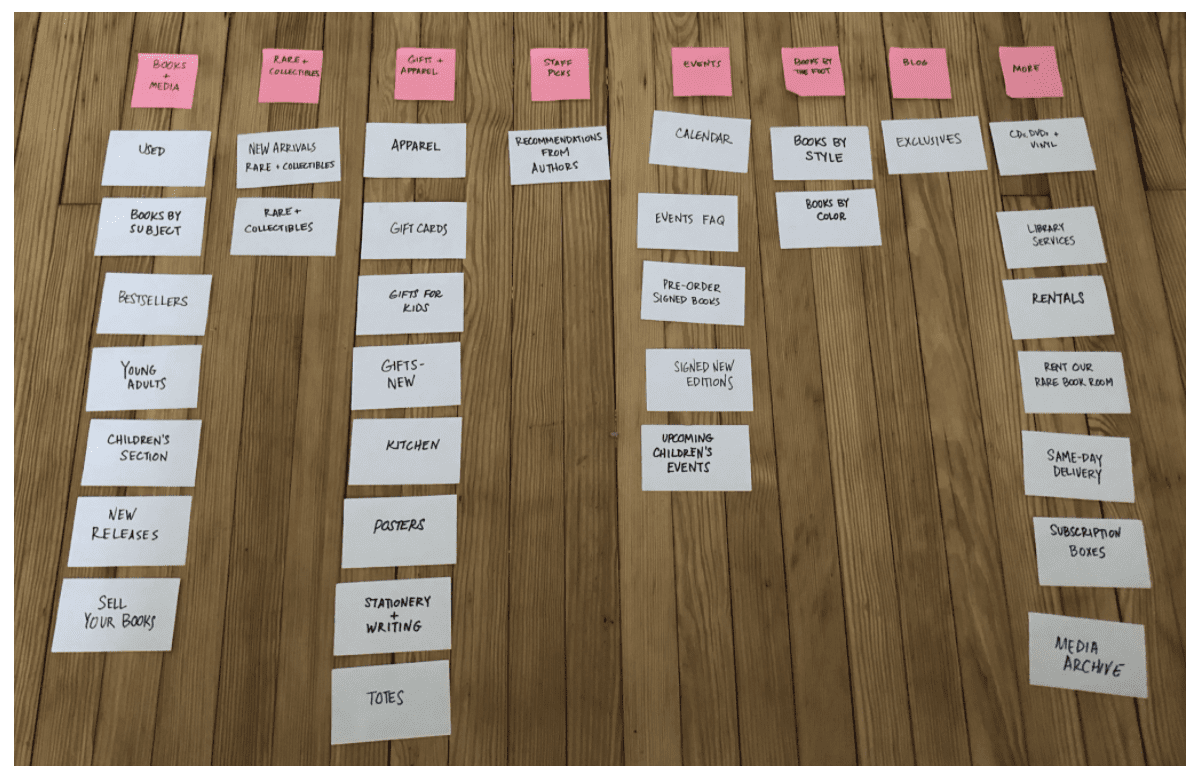

Concept testing and card sorting are two popular ways to see how users will interact with the features, structure, and hierarchy of your app—even without a functioning product.

As you run tests during development, your goals should be centered on validation related to the user experience.

While things might look good and make sense on paper during the wireframing of your app, you need to test those theories from a UI/UX perspective once your design team has actually implemented those elements.

Usability testing is not about gathering generic feedback for your app. You should be using these tests to identify specific problems. So focus your goals around this concept.

For example, let’s say you’re testing an ecommerce app. To determine if your navigation is intuitive or not, you can ask yourself questions like:

- Can a mobile user easily search for a specific product?

- Can users easily add items to their shopping cart?

- Can users complete the checkout process with minimal friction?

These types of questions will help you focus on specific goals for app user testing.

Step #2: Determine the Testing Method

Next, you’ll need to figure out exactly how you’re going to conduct the tests. There are lots of different ways that this can happen. But for the most part, user testing can be segmented into the following categories:

- In-person moderated

- In-person unmoderated

- Remote moderated

- Remote unmoderated

There are pros and cons to each. For starters, moderated sessions typically offer deeper insights because you’ll be able to ask questions, and get feedback, and follow-up with testers in real-time.

Here’s an example. A user might make a comment such as, “this is surprising,” and say nothing else. During a moderated session, the moderator could follow-up by asking, “what was surprising?” You won’t have this option in an unmoderated session.

The downside of a moderated session is that it’s unnatural for users. If you’re trying to emulate real-life scenarios, app users wouldn’t have any guidance or real-time communication with a third party while using the app.

In-person testing has its challenges as well. It’s more labor-intensive, and you’ll have to deal with scheduling. Some test participants feel pressure to “say the right thing” when they’re being watched in-person, whereas they’d be more candid with feedback remotely.

Unmoderated remote sessions are the easiest way to get the most possible tests done for the lowest cost. You’ll also get to test users in a more natural environment. However, you lose the ability to communicate in real-time.

So which option is the best?

There’s really no right or wrong answer here. It all comes down to your personal preferences. You may ultimately decide to conduct user testing in multiple environments with a combination of these methods mentioned above.

Step #3: Select the Participants

Now it’s time to find real users to participate in your tests. Don’t just select random people, or you won’t get accurate test results.

Hopefully, you’ve already identified a target market for your app by now. But look beyond the demographics like age, sex, marital status, and location. Behavioral targeting is much more valuable here. So look for users who are already using apps that are similar to yours.

Recruiting participants that have some interest and prior experience in what your app is trying to accomplish will have much more value than a random user who happens to be a certain age and gender.

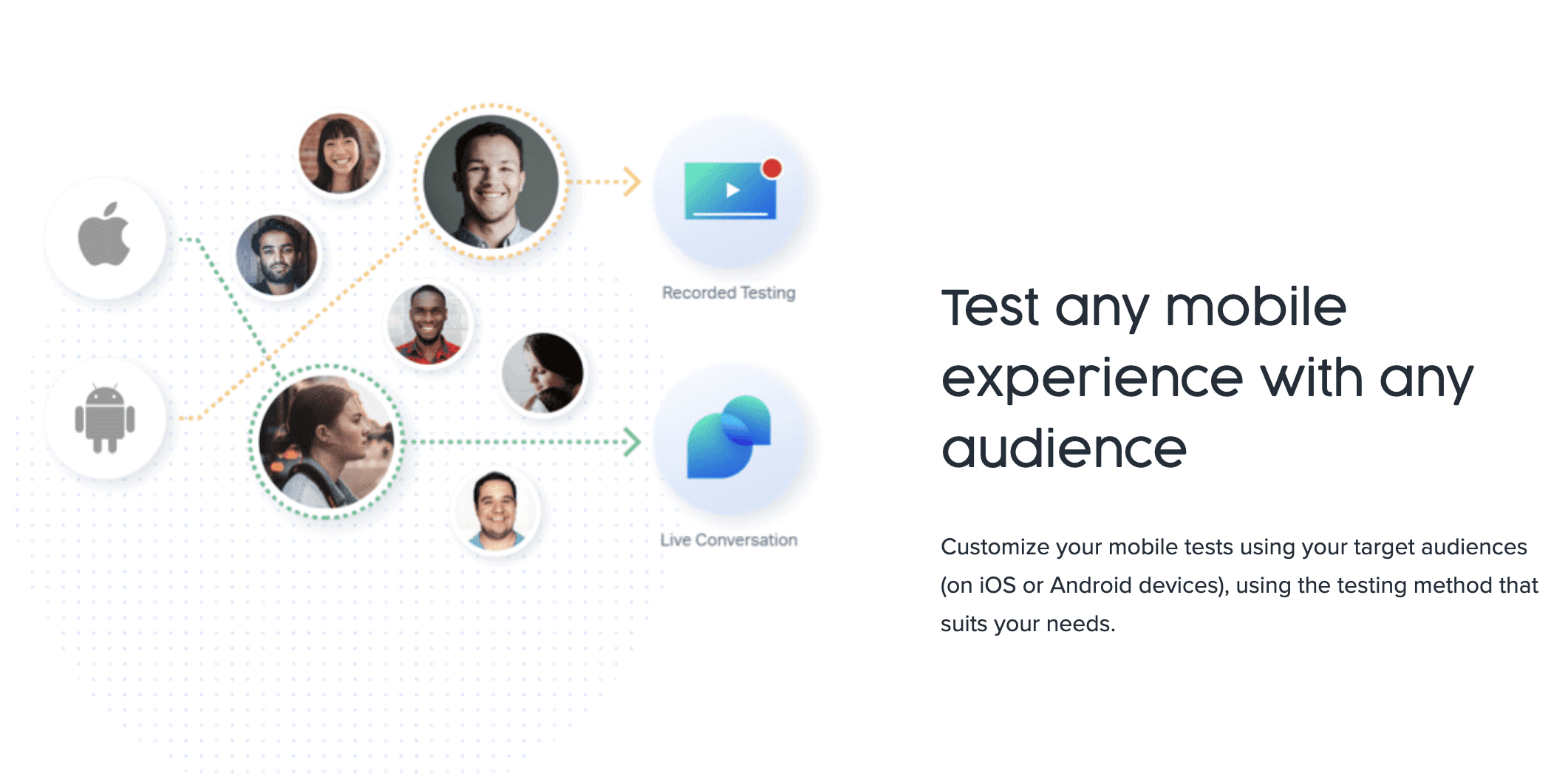

UserTesting.com is a great platform for finding participants and conducting tests. They even have specific solutions for mobile app user testing.

The platform supports multiple testing methods. It’s a popular choice for mobile app prototypes, unreleased apps, apps already available in the Apple App Store and Google Play Store, AR/VR apps, home testing, “out in the wild” testing, and more.

There are plenty of other similar alternatives on the market, but UserTesting.com is definitely one of the most popular solutions for finding and testing participants in one place.

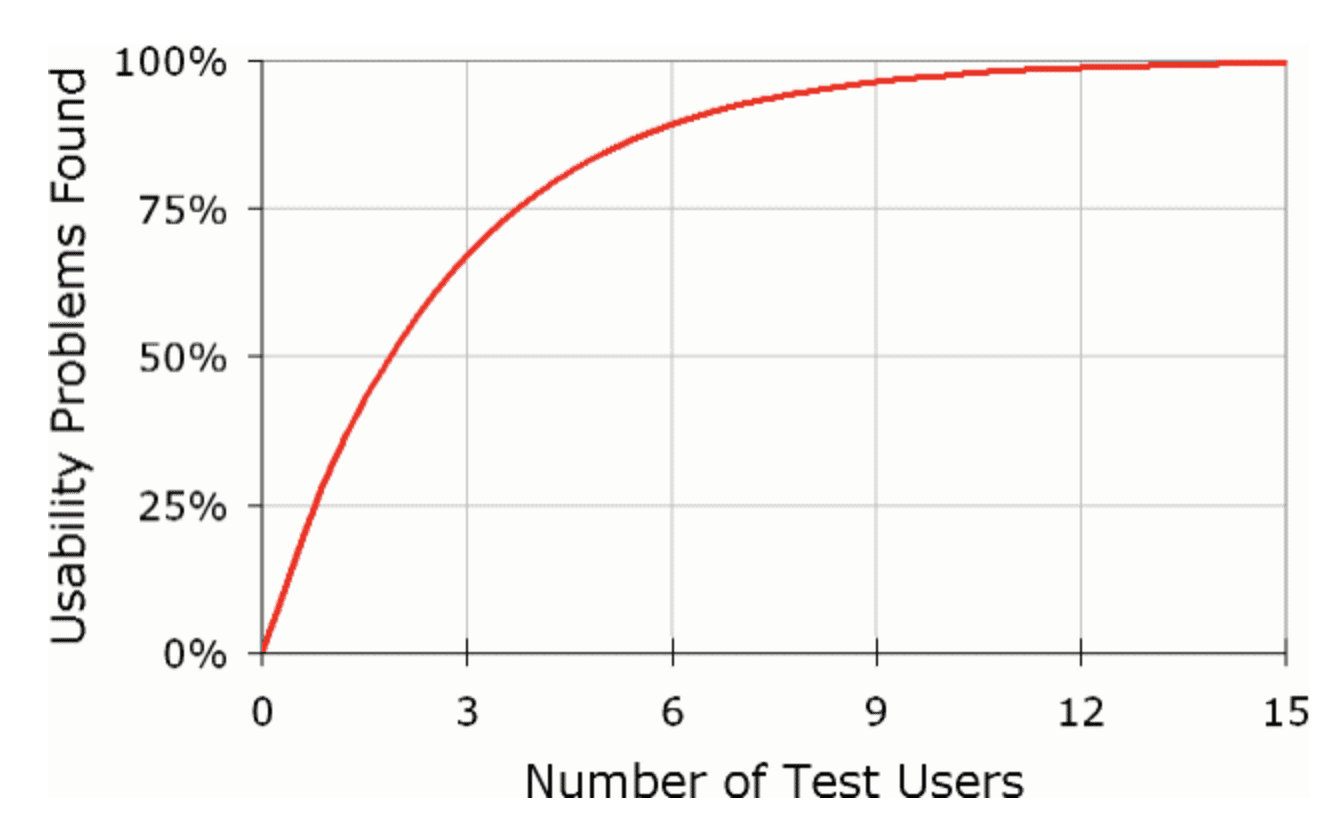

How many testers do you need for an accurate user testing experiment? According to a famous study from the Nielsen Norman Group, five is the perfect number.

The concept here is pretty simple. If you test zero users, you’ll find zero usability problems (obviously). But as you test more and more people, the number of issues you encounter will start to flatten out.

After a handful of tests, you’ll see the same thing over and over again. So there’s no reason to continue observing things that you already know.

Based on this curve, 15 users is the absolute maximum number of participants you’d need to uncover all usability issues. But most experts recommend between 5-7 participants. Some will say up to ten is ok too.

You might need to offer an incentive to recruit participants. The compensation amount should vary depending on the type of test you’re running. For example, an in-person moderated session could be valued at around $50-$100. But an unmoderated remote test might be worth closer to $15.

Step #4: Prepare the Testing Materials and Testing Environment

Once you’ve recruited testers, it’s time to prepare for the test itself.

What exactly are you going to be testing? Refer back to the goals that we established back in step #1. You’ll use the goals to create objectives for the user to complete. You’ll ultimately create a list of tasks, which is sometimes referred to as a testing script.

Set up a realistic scenario for your users. For instance, here’s an example of some objectives you could list for an ecommerce app test:

- Search for a blue dress

- Add a medium-sized red shirt to your shopping cart

- Create a user profile

- Complete a purchase that qualifies for free shipping

- Save your billing details for future purchases

- Complete a purchase with your card saved on-file

In these scenarios, you’re not telling the participants how to complete the tasks. Instead, you’re just telling them what you want them to do. There’s a big difference. The idea here is to give your participants clear instructions but allow them to naturally engage with your app and its usability—this will provide you with the best usability testing results.

You should also prepare follow-up questions and debriefing questions.

If you’re running tests in-person, you’ll also have to prepare a testing environment. Is the test taking place at your office? Are you going to run it in a third-party testing facility? Where will the participants be sitting? Where is the moderator sitting? You must have all of this stuff in order before the test itself. Otherwise, you’ll be scrambling around during your appointments, which will ultimately impact the quality of your tests. Make sure the testing environment doesn’t interfere with the user experience.

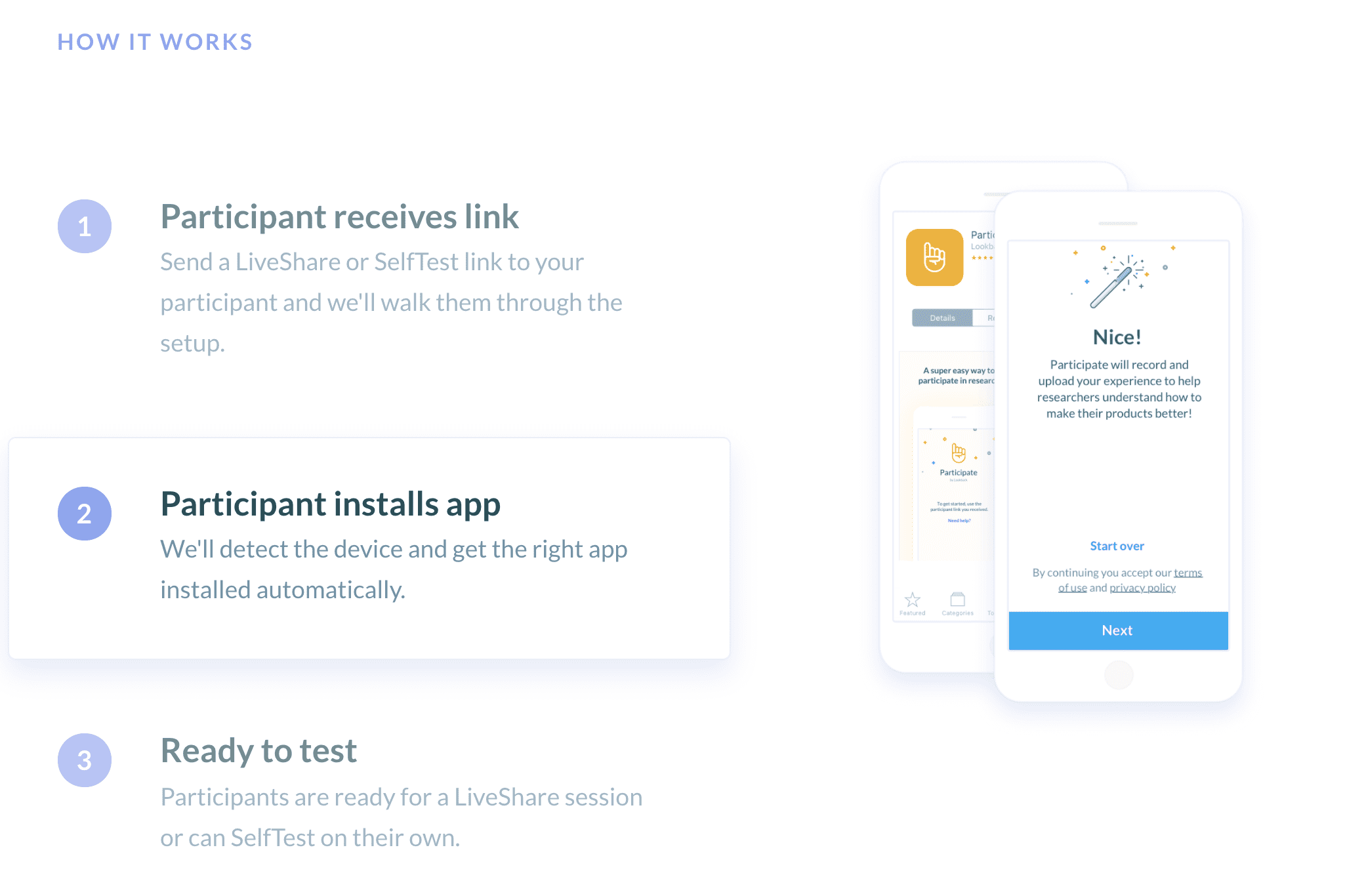

Earlier I mentioned UserTesting.com as a platform for remote app user testing. But Lookback.io is another popular testing tool and perfect for both moderated and unmoderated app testing.

Just make sure you find a platform and finalize your testing environment before you proceed.

You’ll also want to run some practice tests before you start testing actual users. Running into problems or glitches (unrelated to the app itself) during an experiment will definitely de-rail the accuracy and effectiveness of your results. So work out all the kinks associated with your testing environment ahead of time.

Step #5: Run the Test

This step is pretty self-explanatory. After all of your hard work, it’s finally time to conduct user testing for your app!

Surprisingly, this is the easiest step in the process. If you followed everything else I’ve explained to this point, there’s really not much for you to do here. Your participants will already be recruited and have the testing materials to complete your desired objectives.

With moderated testing, you might need to remind participants to think out loud as they complete tasks.

For example, a participant might furrow their brow or tighten their lips throughout the process. In many cases, these actions could indicate some type of frustration or pain point. But it’s better for the user to verbally express those challenges, instead of forcing you to play a guessing game.

Every test should end with debriefing and follow-up questions. Even if the test is remote and unmoderated, you can get those questions over your participants via email or through the testing platform. This is an important part of the design process that shouldn’t be overlooked.

Follow-up questions and feedback need to be completed immediately after the test, while everything is still fresh in the participant’s mind. If they answer these questions at another time, the results will be skewed and not as accurate.

Step #6: Analyze and Adjust

The experiment isn’t over after the test is complete. You still need to go back and analyze the results.

What similar problems did testers encounter? What friction or pain points were associated with your objectives?

Aside from the direct feedback from your participants, you should also go back and observe measurable data. For example, how long did it take them to complete one step of a particular task? The length of time it takes someone to complete an action is a good indication of how difficult it was. In some instances, the amount of time completing a task could also be an indication of how engaged a participant was with your app. These metrics are always helpful.

Once these observations have been clearly identified, it’s time to create an action plan with your team to improve the app. You’ll likely need to make some UI/UX design adjustments to enhance your app.

App Usability Testing Tips and Best Practices

As someone who has conducted countless user testing experiments, I’ve learned quite a bit of useful information over the years. While you’re following the steps above, make sure to keep the following tips in mind:

- Always record your tests (even for moderated sessions), so you can go back and watch

- Don’t make assumptions; provide your participants with SPECIFIC instructions

- Ask mobile users what type of experience, features, and functionality they expect

- Don’t make tasks too complicated (not all participants are tech-savvy)

- Avoid technical terms in your testing script (most people won’t know terms like hamburger menu, UI/UX, etc.). So use common language.

- There is always room for improvement (even if you have a great UX designer)

- Moderators should remain neutral (no positive reinforcement or critiquing during the test)

- Moderators should say as little as possible (to mirror real-life scenarios)

- Run tests on multiple platforms (iOS and Android)

- Participants provide better feedback when presented with comparable options

- Always note visual cues (furrowed brow, smiles, hand to chin, facial expressions etc.)

- Continue conducting user tests for different goals (this is an ongoing process)

If you’re having participants perform tasks that involve transactions, you should always use real money. Fake or monopoly money won’t give you the same results. When real money is at stake, users will take the time to shop around and get the best deal (like they would in the real world)

Following these tips will improve the accuracy and results of your mobile app user testing.

Conclusion

User testing is crucial to the success of any app. It’s one of the most important steps in the design phase of your app as well.

Don’t underestimate the value of user testing. Whether you’re still prototyping or getting ready for launch, you’d be surprised at how helpful these insights will be to the UX of your mobile application.

If you’re struggling with the concept of user testing and don’t know where to start, just follow the step-by-step process outlined in this guide. For those of you who still have questions, feel free to drop a comment or reach out to our Pro Services team here at BuildFire. Good luck and happy testing!