Client Profile

GURU Fitness is more than just a fitness program—it’s a lifestyle dedicated to achieving greatness. The acronym GURU stands for “Generating Unique Results Ultimately,” which reflects the core philosophy of the program.

The program aims to train both the body and the mind, equipping individuals to overcome life’s everyday challenges. By incorporating varied and dynamic workouts, GURU Fitness ensures that participants are always prepared to push their boundaries and reach new heights.

Inspirational Discussions and Inclusive Coaching

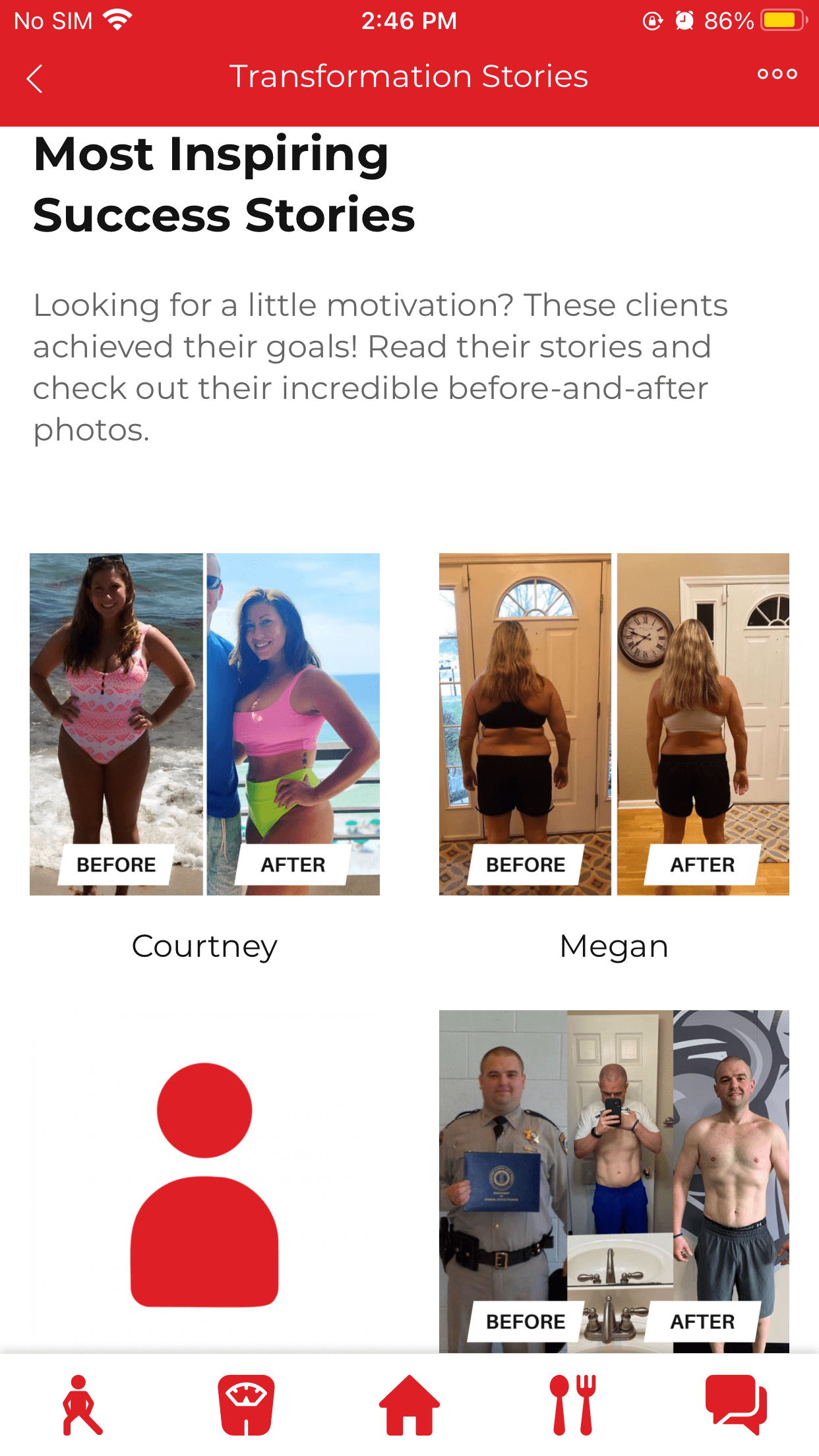

GURU Fitness recognizes that true transformation goes beyond physical exertion. After each workout session, participants engage in inspirational discussions that help them stay motivated and focused on their goals. These discussions foster a supportive and empowering community, encouraging individuals to share their experiences and learn from one another.

Moreover, GURU Fitness accommodates individuals of all fitness levels, providing exceptional coaching tailored to each person’s needs. The program strives to educate, motivate, and empower its participants through personalized guidance, content, and a strong sense of community.

120% Commitment to Progress and Dreams

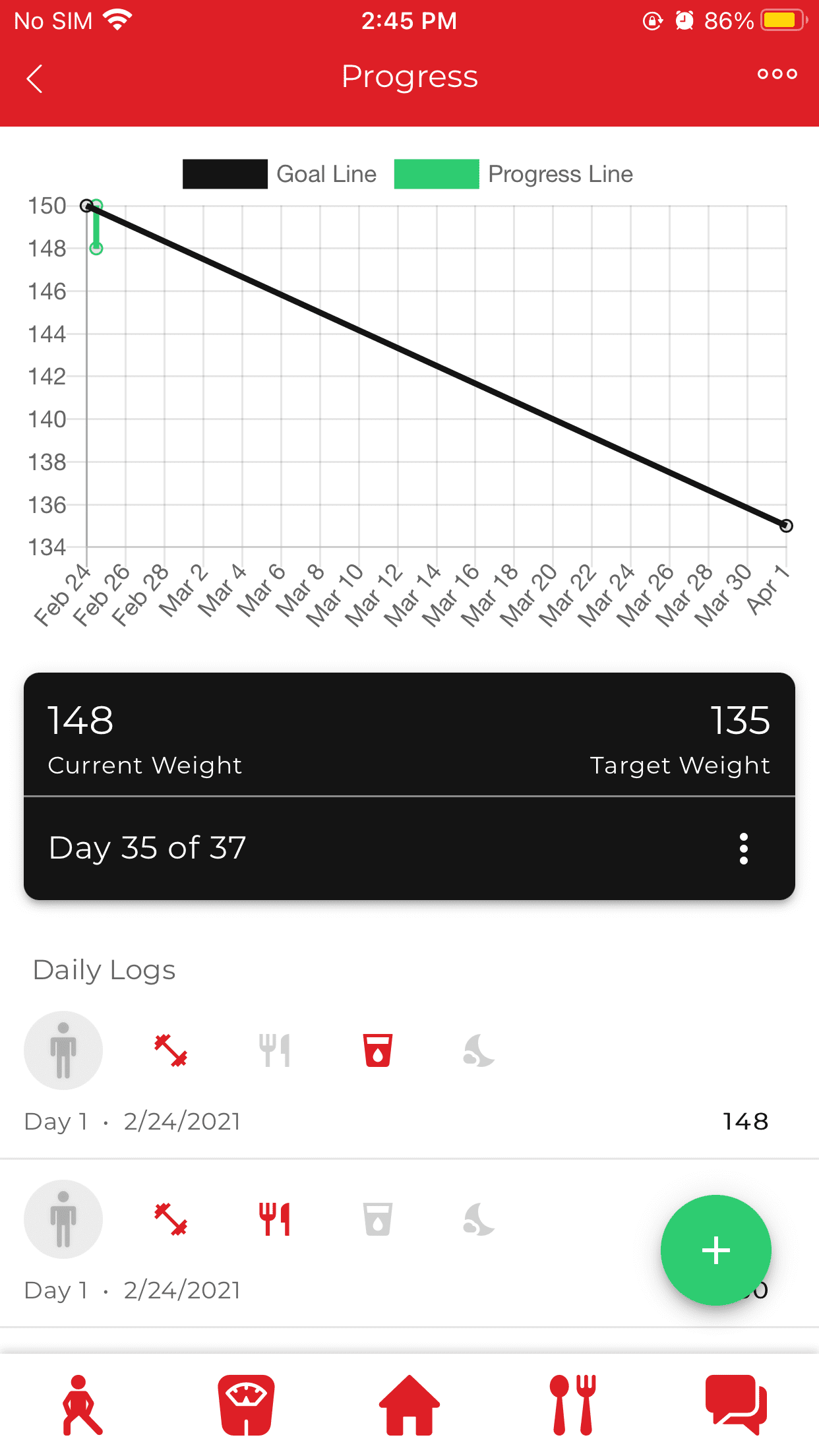

At GURU Fitness, the team is fully dedicated to the progress and dreams of each individual they train. They give their all, going the extra mile to ensure that everyone inches closer to their goals day by day. With a relentless commitment to providing quality coaching, content, and community support, GURU Fitness aims to empower individuals to unlock their full potential.

By embodying the values of dedication and perseverance, GURU Fitness inspires participants to reach new heights and make their dreams a reality.