Nobody is perfect. App developers and mobile app resellers are no exception to this rule. Throughout my years overseeing the app development process, I’ve seen first-hand about almost all mobile app development mistakes under the sun.

Some of these developer mistakes are more significant than others. Whether it costs you time, money, or both, these errors can be frustrating.

But for those of you who are just getting started with app development, whether it be as a reseller or business owner, you have a huge advantage here.

I’m sure you’ve been told to follow the path of those who succeeded before you. Well, you can also avoid the path of people who failed before you; learn from their mistakes.

Nobody intends to make a mistake during the app development process. 99% of the mistakes I’ve seen on a daily basis could have easily been avoided if the developer knew about them ahead of time. That’s what inspired me to write this guide.

Before you start a new development project, you need to review these common 11 mobile app mistakes. By avoiding app development mistakes, you’ll endure less frustration and increase your chances of building a successful app.

Mistake #1: Neglecting Research and Due Diligence

Overseeing app development has taught me that people are impatient by nature. They want to dive in and start creating immediately, without taking the proper steps ahead of time.

If this sounds like you, I admire your enthusiasm. But you need to slow down and conduct your due diligence before you proceed.

Taking the time to find the best platform and solution for app development now will save you months or even years of frustration down the road. The app creation tool you choose can make or break the success of your project, so don’t rush this decision.

There are so many different ways to build an app:

- Coding on your own.

- Using an app creator on your own without coding.

- Hiring an agency.

- Working with a freelancer.

- Becoming a white label reseller.

The list goes on and on. Plus, there are different subsections within each option. For example, there are small local agencies, large international agencies, and everything in between.

You can’t make this decision in ten minutes while browsing the web at a local coffee shop. It takes time to find the perfect app development solution for your needs.

This process can be compared to buying a car. You don’t just show up to the dealership one day on a whim and leave with a car an hour later. You’ll read consumer reports, customer reviews, take test drives, and shop around different dealerships.

The same process can be applied here. Read customer stories and case studies before you choose a development company. Subscribe to their newsletter. Request a consultation. Try a demo or free trial.

This is the only way to truly find the best development platform for your reseller agency or business app.

Mistake #2: Poor Budget Management

Blowing through a budget is another common developer mistake that I see on a regular basis. There are a few main reasons why this happens:

- Inaccurate budget estimate from the start.

- Failure to plan for all components of the project.

- Unexpected costs.

It’s important that you have a rough idea of how much your app will cost from the beginning. You can use tools like a mobile app cost calculator to help get an accurate estimate.

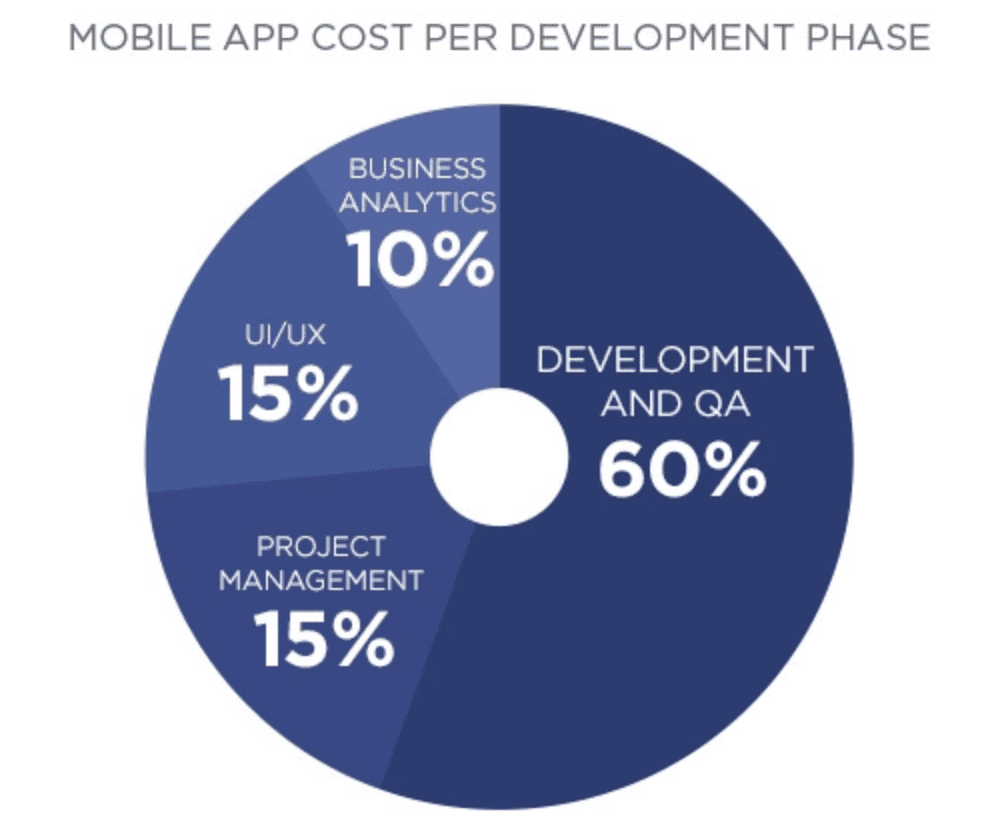

But the initial development isn’t the only thing you need to plan for. Other phases need to be taken into consideration when you’re creating a budget.

Your budget should also allocate funds for unexpected costs that could arise along the way.

If you decide that you want to add new features or make changes to your initial plan, your project won’t go over-budget if that was built into the estimate.

It’s important that you set realistic budget expectations from the beginning. Lots of developers have a number in mind that they think will be sufficient to build an app, based on something they read or a conversation they had with a friend. But so many factors must be taken into consideration here.

If you keep up with the latest mobile app development trends, you’ll learn that technology is constantly evolving. Features like AI, AR, and other integrations will impact your budget.

For those of you interested in becoming a mobile app reseller, you need to have an accurate budget to estimate your profit margins correctly.

Mistake #3: Not Creating an MVP

Diving right into the final build is another common mistake made by app developers.

An MVP (minimum viable product) will help you test the app and evaluate its performance. During the MVP stages of development, the app will only be comprised of essential features.

Here’s an analogy. Let’s say you were building a car.

The final product will have a radio, a GPS system, leather seats, automatic windows, and a new paint job. But an MVP of that car just needs to have four wheels, a frame, steering wheel, and an engine. As long as the car does what it’s supposed to, it’s an acceptable minimum viable product.

An MVP is not an experiment for your app. This is another common app mistake.

Back to the car analogy. You wouldn’t build a motorcycle or a helicopter as your MVP if the final product is supposed to be a four-door sedan.

So if you’re building an HR mobile app to improve employee efficiencies, a social media app isn’t a viable MVP.

Instead, you’d want to focus on the core components of the app. Such as building individual employee log-in capabilities and the ability to send push notifications for announcements. As development continues, you can add features like access to payroll information and benefits.

Mistake #4: Poor UI/UX Build

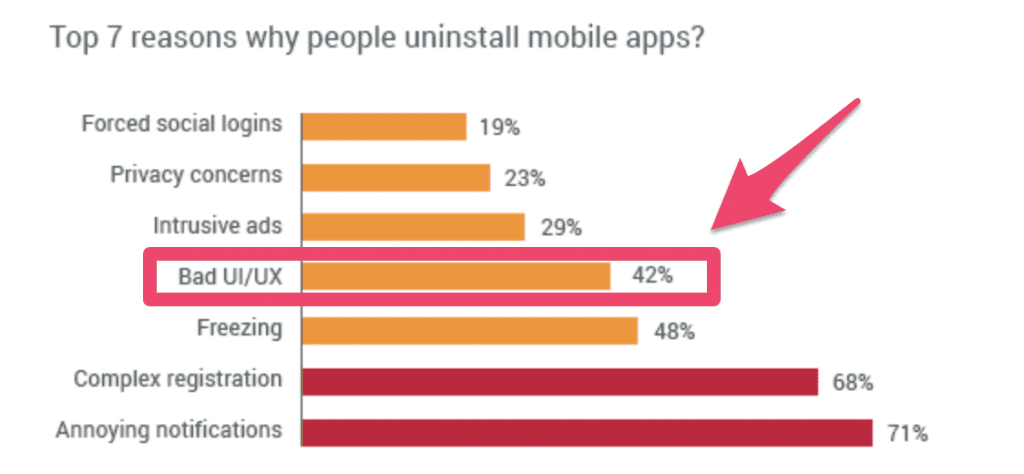

Sometimes we get so lost in development that we forget about how the app will actually be used. Neglecting the user interface of an app is a mistake that needs to be avoided at all costs.

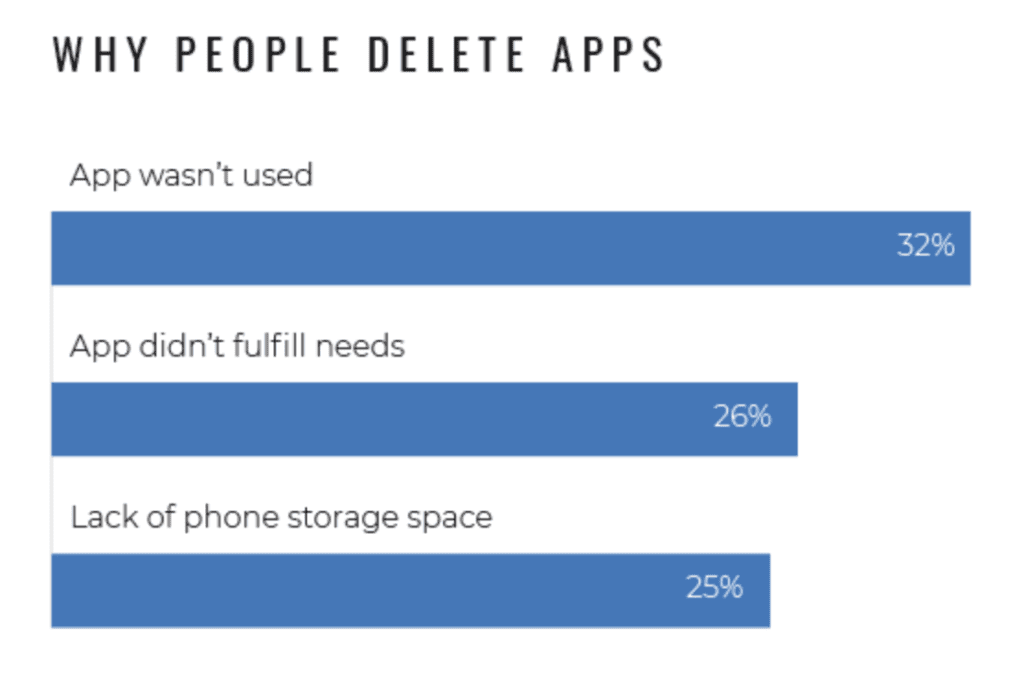

A poor UI/UX design is one of the top reasons why people uninstall apps.

People have certain expectations when they open an app. Follow the lead of the most successful and popular apps on the market today as an example.

All of these apps have simple navigation, a search function, and the home menu that can be easily accessed from any screen.

Sometimes developers make the mistake of trying to get too creative with the UI, which ultimately hinders the user experience.

Here’s an analogy. When you visit a website, you’re expecting the main menu to be at the top of the screen, right? That’s how you’ll navigate to different pages and find your way around the site.

Now, what if you went to a website, and the main menu was in a grid at the bottom right side of your screen?

Technically, that’s not incorrect. People can design a website however they want to. But the users will be frustrated with this design since it’s not what they’ve grown accustomed to.

The same concept can be applied to your mobile app. Don’t try to reinvent the wheel and win the most innovative homepage design in the history of app development.

Stick to what works. If the user is forced to make three or four clicks just to return to a home screen or navigate to another screen in the app, they will not enjoy the app experience.

Prioritize UI, or else you’ll have lots of unhappy app users.

Mistake #5: Failing to Test Properly

I briefly mentioned testing earlier when we discussed MVPs. But to have a successful mobile app, you need to take your testing to the next level.

Testing is an ongoing process and needs to be performed throughout the entire development process. Not only will it improve the user experience, but it’s the only way to work out any bugs or problems with the app.

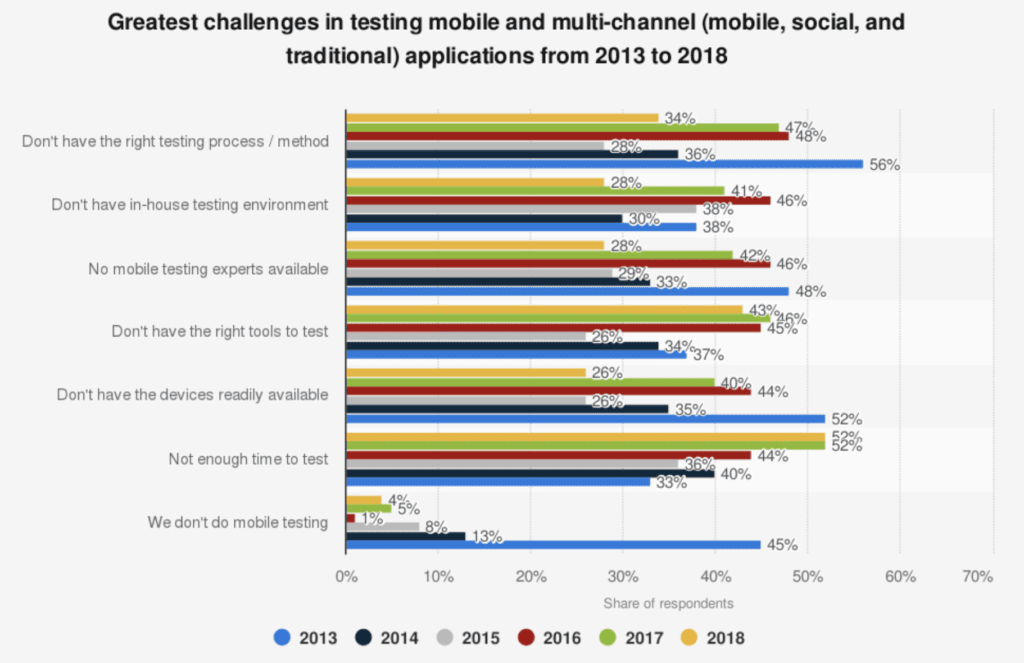

Here’s an overview of the most common challenges in mobile app testing over time.

As you can see from the graph, the vast majority of developers test their apps. That’s no longer a problem.

But several challenges still remain, which hinders the testing process.

To combat some of the most common testing mistakes and barriers, follow these tips and best practices:

- Define your testing process and procedure. (How often will you test? Who will test? Etc.)

- Have a dedicated in-house testing environment.

- Use both in-house and outsourced mobile app testing experts.

- Get the right tools and equipment to facilitate your tests.

- Schedule time for testing.

Using in-house and outsourced experts to test your app is crucial. A developer or team of developers working on an app every day will have a bias. They know how the app works and what it’s supposed to do. An in-house tester may not think the UI needs improvement if they were involved with the design process.

But a third-party expert who is impartial and has never seen the app before will be able to provide much better feedback.

Mistake #6: Building For Too Many Platforms

Depending on the purpose of your app, you might be tempted to make it available for as many users as possible. While this obviously has its upsides for mobile app marketing, it can create challenges from a development standpoint.

If you’re going to build a traditional native mobile app, creating an iOS and Android app will likely double your budget.

Both projects will be treated as two separate development ventures. So if you’ve never built an app before, taking on two builds at the same time is a daunting task.

Rather than accelerating your initial development costs and starting something that’s too much for you to handle, stick to just one platform if you’re building a native app.

Alternatively, you can build for iOS and Android simultaneously using an app builder. These platforms reduce your development costs and timeline while giving you the ability to create an app without writing a single line of code.

If you want to learn how to code or work with a partner that will code a native app from scratch, that’s fine. I’d just focus on one platform if you go that route. Otherwise, using an app builder will be the best way to avoid these problems altogether.

Mistake #7: Poor Communication During Development

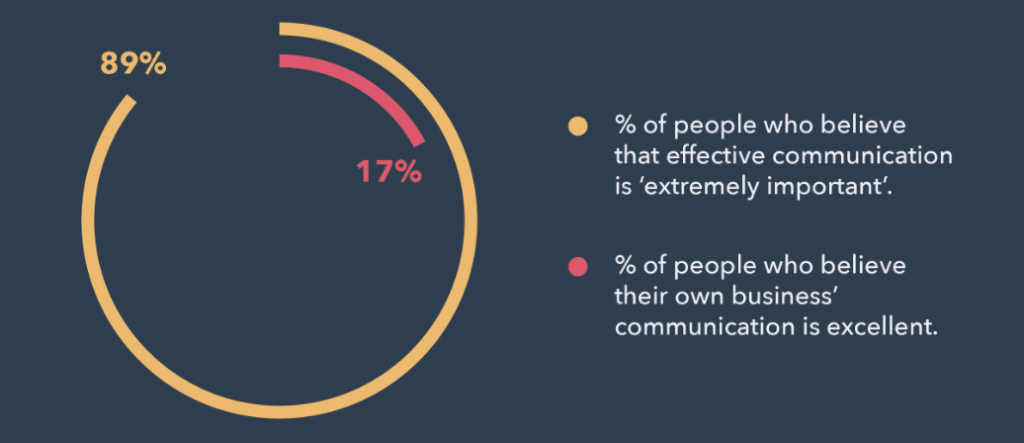

The majority of mobile app failures can be traced back to poor communication during the development process.

While most people agree that effective communication during a project is extremely important, just a small percentage of people believe that their business is achieving that.

This statement holds true for any project, but the stakes are magnified when it comes to something as important as mobile app development.

The only way to avoid this mistake is by prioritizing communication from the beginning.

I’ve supervised dozens of app development projects over the years. If I’ve learned one thing, it’s that there is no such thing as over-communicating. Keeping your partners, colleagues, development team, or whoever else updated with your progress or ideas can’t hurt you.

Maybe you repeat something that was already said. So what? It’s better than assuming everyone is on the same page when they really aren’t.

If you’re hiring a developer to build an app for you, that person isn’t a mind-reader. You need to be clear throughout every stage of what your expectations are.

For those of you who plan to white label and resell apps, your communication skills could make or break the success of your mobile app reseller business. Unhappy clients are expensive and can even give you some sleepless nights. It’s worth the extra five minutes every so often to get organized.

Depending on the size of the app development project, you can have daily, weekly, or bi-weekly meetings with everyone involved. A quick status update from each member of the team is usually enough to get the job done.

Mistake #8: Going Overboard With Features and Functions

Apps today are seemingly limitless. They can do just about anything that you can imagine.

With that said, it doesn’t mean that your app needs to include every app feature and function available just because it’s possible. Stick to the core features of what your app really needs to function properly.

Adding too many features will set you up for loads of problems down the road. From an initial development standpoint, it’s going to increase your budget with each new feature you add.

Jamming your app full of features can even hinder its performance. Apps with too many features are more susceptible to bugs, errors, and crashes.

Furthermore, adding features will impact the size of your app. Research shows that one in four people will delete an app for a lack of phone storage.

This also makes it a challenge to update your app, which we’ll talk about in greater detail shortly.

Since app development and technology is so cool, it’s tempting to add new features. But you need to think twice and ask yourself if new features are actually necessary. If it doesn’t add value to the app, then leave it out.

Let’s say you’re building an ecommerce app. Can you add a calculator, flashlight, calendar integration, and social media log-in? Sure. But why would you?

An ecommerce app is complex enough without all of the unnecessary bells and whistles. So just focus on features needed to facilitate mobile commerce transactions.

Mistake #9: Partnering With the Wrong Development Team

I’ve seen good app ideas fail because the wrong person developed it. This is an expensive mistake that needs to be avoided at all costs.

Ironically, one of the reasons why people pick the wrong development team is because they are price-sensitive. They try to save money by outsourcing development to a freelancer overseas at a fraction of the rate for an agency in the US.

Then that freelancer stops responding, falls behind schedule, or delivers an app that doesn’t meet your expectations.

You’ll want to find a development team that will give you as little or as much control during the process as you choose. Do you want to develop the app on your own? Do you want the developers to build it for you? Do you want to do most of the work with a little bit of help and guidance along the way? Finding a developer that can meet all of those needs will be your best option.

If you want to become an app reseller, choosing the right development platform is the most important step in the process.

That development platform is your entire product. If that team doesn’t provide you with the support, resources, and materials required to service your clients, you’ll be in a world of trouble.

Mistake #10: Not Preparing For Updates

It’s a common misconception that app development ends when the app launches. That’s far from the case. In reality, development never stops. No app is perfect, and you’ll need to make improvements on a regular basis.

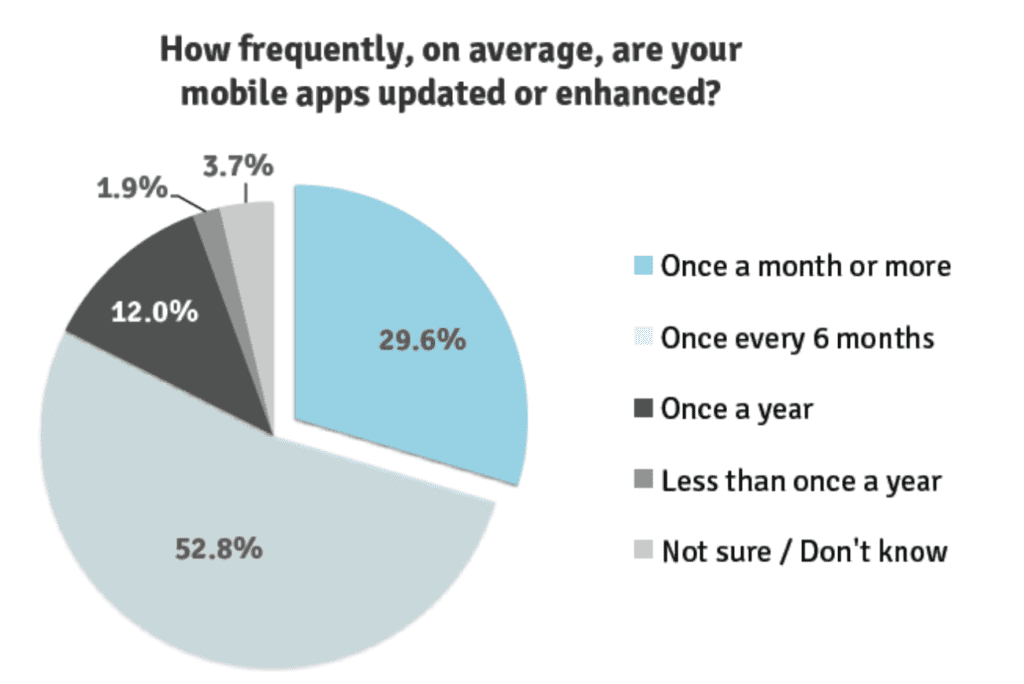

About 30% of apps are updated at least once a month. More than 80% of apps are updated every six months.

You must plan for these updates from the beginning. Updates will impact your budget, as well as your decision to choose one developer over another.

Updates are required to improve the user experience, eliminate bugs, and remain compatible with the latest operating software on various devices.

If you’ve spent every last penny in your budget for the initial app launch, you won’t be able to make any updates without coming out of pocket.

Choose an app builder that provides full-service and maintenance even after you finish building the app.

As a reseller, you need to keep these app updates in mind for your clients as well. Your white-label service provider must make this easy for you. At the end of the day, updates can benefit your bottom line. You can continue to generate income long-term even after the app has launched by providing updates and additional support services to your clients.

But that’s only possible if you’re on the right reseller program with a development platform that can provide those needs.

Mistake #11: Mirroring Your Mobile Website

Lots of business owners understand the importance of having a mobile presence. So there’s a good chance that you already have a mobile-friendly website.

After learning that mobile apps convert higher than the mobile web, you might be interested in building an app for your business. Don’t make this app a clone of your website.

There’s a reason why apps perform better than mobile sites. Apps offer features and functions that a mobile website cannot. Mirroring your app after the mobile site would be a waste of your resources and opportunity.

Plus, users have different expectations for an app compared to a website. The purpose of the app is to make the customer journey easier and provide enhanced value to the users.

If the app isn’t different than the mobile site, why should they bother downloading the app?

Your app can have some similarities as your website, such as the color scheme, theme, and brand image. But beyond that, the app needs to create a completely different user experience.

Conclusion

Like any big project, developing an app can be frustrating at times. Mobile app development mistakes happen to everyone, including myself.

But if you understand the most common developer mistakes, you can avoid them altogether.

Whether you’re building an app on your own, looking to hire a developer, or interested in becoming a mobile app reseller, avoiding the mobile app development mistakes in this guide will save you time, money, resources, and headaches in the long run.

Will you still make mistakes along the way? Probably. But it won’t be anything that is insurmountable.

Keep checking back and subscribe to the BuildFire blog to get the latest updates on development tips and best practices.