Apps make life much easier. We use apps in our personal lives for things like banking online, booking flights, getting directions, or doing dozens of other tasks from the palms of our hands.

But mobile apps are also highly beneficial in the workplace.

Mobile employee apps are perfect for internal communication purposes, managing workflow, and providing your staff with self-service HR tools.

Apps are especially useful for organizations with a deskless workforce. Mobile workers don’t have easy access to computers or laptops at a moment’s notice. But their smartphones never leave their side.

Workforce apps are growing in popularity. In fact, 87% of businesses depend on employees accessing business apps from their smartphones.

That’s not all. Your employees want mobile apps. 59% of workers say that organizations are too slow at incorporating apps into the business model. But 60% of employees say that workforce apps directly improved their personal productivity.

So which apps are the best?

I’ve identified the top 11 apps that your business can use to manage its mobile workforce. I’ll outline the features, benefits, and any potential drawbacks of each one below.

1. Slack

Slack has quickly become one of the world’s most popular business apps for internal communication. This instant messaging tool for iOS and Android is leveraged by large enterprises, small businesses, and everything in between.

It’s trusted by big names like Airbnb, TD Ameritrade, Target, Cole Haan, Zendesk, Fox, and HubSpot.

Slack has over 12 million daily active users across 150+ countries. 65 of the Fortune 100 companies use Slack.

Whether you have remote employees or field workers performing jobs on-site, they’ll always be kept in the loop with their team. Whether they have questions or need assistance related to a particular job, or just want to give a quick status update, Slack delivers messages in real-time.

Slack allows you create communication channels for different teams. Let’s say you’re a contractor. You could create a separate channel for each job or each crew.

Use Slack to communicate with freelancers, third-party contractors, or even staff from other businesses that you’re working with.

This app has a wide range of solutions and use cases for employees related to:

- Remote work

- Engineering

- Distance learning

- Sales

- Financial services

- IT

- Human resources

- Customer support

- Project management

- Media

Another reason why Slack ranks so high on our list is because it integrates with 2,000+ other apps and tools you might already be using.

In addition to instant messaging, you can leverage Slack for audio and video calls. Let’s say you have an on-site technician making a repair at a customer’s house. They can video chat with someone in the office if they need assistance or want to show them progress in real-time.

The app is so popular that it’s become a verb. We use it here at BuildFire. It’s not uncommon for someone to say something along the lines of “Slack me later.”

With all of this in mind, Slack does have its fair share of restrictions. It is not an all-in-one solution for managing your mobile workforce. It’s simply an effective communication tool.

2. Trello

The Trello app is an exceptional tool for managing productivity in the workplace. For single projects or ongoing work, it’s an ideal project management solution for small and large teams alike.

Here’s how it works.

First, you create a Trello “board.” The board can be used for anything from managing your company’s blog to handling workflow status updates for field service technicians.

Within each board, you can create a list. Lists are columns that can be used to define the progress for different tasks and projects.

Here’s a simple example. Columns for field service workers could be:

- To be scheduled

- Scheduled

- On-site

- Done

Every time you have a new project, simply create a “card” and place that card in the respective column. You can create subtasks within that card, such as “called client” or “left a message.” Cards can have due dates and be assigned to specific people within your team.

Let’s continue using the example above. If you schedule a new job for a field service technician, you can put the card in the “Scheduled” list and assign it to the designated employee.

The card can include details about the job, including the address, customer name, and anything else that needs to be done.

Once that employee arrives at the job, they can simply move the card to “On-site” to keep the entire team updated. They can take notes on the card, upload documents, pictures, and complete subtasks like “provided estimate” or “fixed broken sink” (or whatever else you’re doing out there).

If your mobile workforce needs an app for project management, Trello is an ideal solution for you. You can join the millions of users leveraging this tool.

It’s worth noting that Trello isn’t perfect. While you can tag team members and add comments to cards, it doesn’t really provide real-time communication, instant messaging, or audio and video calling features.

Like most of the apps on our list, the app is intended for just one specific purpose. In this case, the purpose is project management.

3. allGeo

Formally myGeoTracking, allGeo is a solution designed specifically for field service workers. The platform offers multiple mobile employee apps for different use cases.

- Field Service Visibility — Monitor time and location on the job.

- Field Service Time Clock — GPS time and attendance system.

- Field Service Safety — Monitor employee safety on-site.

- Field Service Inspection — Collect data with forms and checklists.

- Field Service Dispatch — Real-time notifications and messaging.

- Field Service Milage — GPS mileage tracking and real-time location.

- Field Service EVV — Geofence-based tracking for compliance.

- Field Service Load — Automatic status updates including ETAs.

As you can see, allGeo has a field service app for nearly every mobile employee management tool that you can think of. Unfortunately, none of these come with internal communication features.

It does have some HR and HCM functionality. The apps can integrate with payroll tools like QuickBooks and Paychex. But it’s somewhat limited in terms of what you can accomplish with this.

Another downside of allGeo is the fact that all of these apps are separate from each other. So if you want multiple features, you’ll have to use more than one app. This can get messy and confusing.

allGeo does have a custom app solution for these purposes. But overall, the individual apps function better on their own.

With all of that said, these are still top mobile employee apps for field service workers if you need just one of the management functions listed above.

4. GoToMeeting

GoToMeeting is another mobile employee app with a specific point of emphasis. As the name implies, this app is used for holding virtual meetings.

The app has features for both audio and video meetings that can be managed from smartphones and tablets. It’s an excellent way for remote employees or staff working on different job sites to communicate in real-time.

With a mobile workforce, you lose the ability to hold conference room style meetings at the office. GoToMeeting makes it possible for you to hold virtual conferences.

Top features for GoToMeeting include:

- No meeting time limits

- Business messaging

- Personal meeting rooms

- Calendar integrations

- Up to 250 participants

- Unlimited cloud recording

- Meeting transcriptions

- Diagnostic reports

- Admin center

You can access GoToMeeting from your computer as well, which is very useful. For example, let’s say you’re in the office but want to give a presentation to all of your remote staff. You’ll be able to present from your computer while giving your mobile workforce the ability to join from their smartphones and tablets.

GoToMeeting does have a messager feature as well. But it falls short compared to solutions like Slack, which we discussed earlier.

I like the fact that GoToMeeting seamlessly integrates with Office 365. It’s a nice bonus for those of you who are already using this tool for scheduling and staying organized.

As with most of the other apps on our list, GoToMeeting has its fair share of restrictions and limitations. It’s strictly an app for audio and video meetings or conferences. It’s not going to integrate with your payroll system or give your employees access to timecards, handbooks, benefits, or anything like that.

5. Kronos

Kronos is an all-in-one solution for managing your mobile workforce.

The company was initially founded 40+ years ago back in 1977. At the time, they specialized in time management by revolutionizing employee time clocks. Over the years, Kronos has been able to adapt with the times and modernize its brand with apps and other workforce management tools.

Kronos has solutions for a wide range of business needs, including:

- Time and attendance

- Employee scheduling

- Labor activities and analytics

- Benefits administration

- Acquisition and onboarding

- Talent management

- Payroll

- Human resources

The company has mobile employee apps and solutions for businesses across multiple industries. Kronos has tools for health care, retail, banking, higher education, government, manufacturing, and more.

Kronos offers product suites that encompass multiple workforce management tools into single solutions.

While Kronos is undoubtedly a leader in workforce management, the app itself falls short of the desktop solutions. Based on user reviews and ratings, there are lots of performance issues. The Kronos app has just a 1.6/5 rating on the Apple App Store. The 3.2/5 rating on the Google Play Store is a bit better, but still not up to par with what we’d like to see.

6. BambooHR

As the name clearly indicates, BambooHR is a human resources solution.

This mobile employee app is a modern way to manage your mobile workforce. It gives your staff the ability to check and access crucial HR resources from anywhere. From requesting time off to looking up a coworker’s contact information, BambooHR has it all.

One of the best features of the app is the calendar. It gives management and employees clear access to who is working each day, who’s on vacation, and who has time off coming up.

Everyone will have access to phone numbers, email addresses, and other important contact information for their coworkers. This makes it easy for your staff to stay in contact.

Other top features include:

- Time tracking and payroll tools

- PTO management

- Hiring and onboarding

- Offboarding

- Employee records

- Workflows and approvals

- Reporting and analytics

BambooHR is definitely one of the best mobile employee apps for HR management on the market today. It offers employee self-service tools as well as management and supervisor benefits.

Overall, the app is very easy to use and integrate with any business. Unlike other apps on our list, all of these functions can be managed in a single solution.

With that said, not every feature comes standard with the BambooHR app. Time tracking, payroll, performance management, and other advanced features need to be added separately.

Additionally, BambooHR doesn’t have any features beyond HR functionality. It’s not made for internal communication, task management, or anything else that falls outside the scope of human resources.

7. Google Drive

Google Drive is something that most of you are probably familiar with. Lots of us (including myself) use Google Drive in our personal lives for storing files in the cloud.

But this is an excellent solution for managing files at work as well.

As a cloud-based solution, you can access Google Drive from anywhere. From documents to spreadsheets and images, your entire team can collaborate on files with this app.

While the application of Google Drive’s features aren’t necessarily geared towards specific business functions, you can easily find ways to make the app work for your needs.

Here’s an example. Let’s say you have field service workers that need to take pictures while on a job site. Your staff can simply take photos using the camera on their smartphone and then upload those images to a folder in Google Drive directly from the app.

You can set up folders for each project, client, or organize your files in whatever way you see fit.

Once a file has been uploaded to the drive, anyone with access can see it. So another employee back at the office could see any uploads in real-time from their smartphone or computer.

Set up Google Sheets to manage workflow tasks on a spreadsheet. Or use Google Docs to provide your mobile workforce with important information about clients, jobs, or training material.

If you have a small team and need a simple solution for file storage and communication via mobile employee apps, Google Drive is a free and simple solution. You’ll just have to get creative with how you set everything up to stay organized.

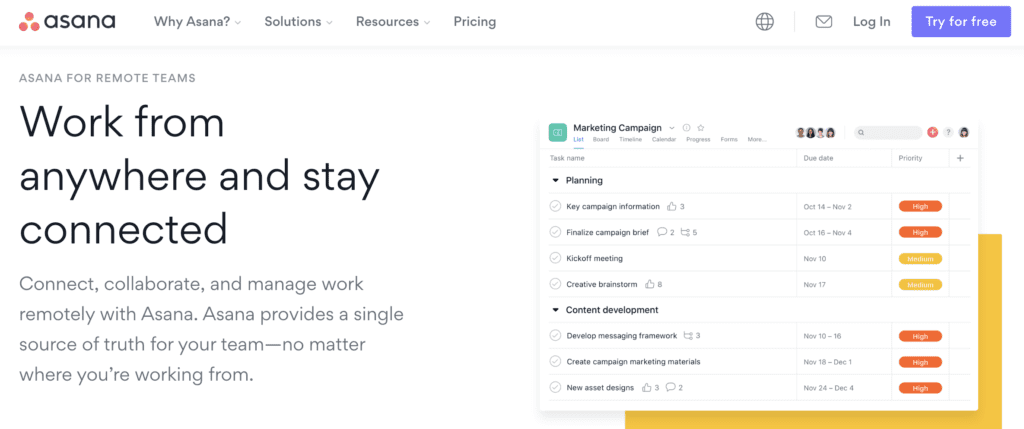

8. Asana

The Asana app is very similar to Trello, which we talked about earlier. It’s a mobile workforce app made for project management.

Simply create a task, drag it to the respective status column in the workflow chain, and assign team members to collaborate.

Asana is a little bit more advanced than Trello in terms of its features and capabilities. Beyond basic workflow management, Asana is better for tasks with multiple action items. The app dashboard makes it easy for your remote staff to manage and clear any action items assigned to them.

With Asana, you’ll also be able to organize projects and tasks based on level of priority. Employees can attach files, add comments, and manage campaigns from a simple and easy to use dashboard within the app.

Asana integrates with other tools, including other solutions on our list, like Slack, Google Drive, Gmail, Dropbox, and more.

I’d say Asana is geared more towards remote digital marketing teams as opposed to field service workers. There are specific tools and features for mapping out and tracking plans that are just better for this type of remote work.

You can use the Asana app to automate certain processes as well. This is ideal for maximizing efficiency and productivity.

If your organization is in a creative industry with remote workers, the Asana app will be a top choice for task management. But it’s not an all-in-one tool for managing a mobile workforce. The communication tools are limited compared to other options on the list, and HR functionality is non-existent.

9. Hangouts Meet and Hangouts Chat

Hangouts Meet is the new and improved version of Google Hangouts. Commonly referred to as just “Meet” for short, this app is a communication tool that’s included with G Suite.

So for those of you who already have G Suite for other business purposes, you can start using Hangouts Meet for video calls directly from the app.

This app is a basic tool for video meetings and conference calls. It’s better for smaller groups and even one-on-one video calling.

Google offers a separate app called Hangouts Chat for messaging. You can set up different chat rooms for projects, teams, or just use it for one-on-one conversations.

Both of these apps are better for smaller teams who are already using G Suite. It’s unfortunate that the calling and messaging features aren’t integrated into a single solution. Your remote workforce will have to switch back and forth between both, which can be annoying.

For example, let’s say two employees are messaging via Hangouts Chat. Then they decide that it would be more productive if they hopped on a call. Your staff would be forced to switch apps and connect from there instead.

But if you’re a low volume user or working with third-party contractors or freelancers, Hangouts Meet and Hangouts Chat are both sufficient for basic usage.

10. Dropbox

Dropbox is similar to Google Drive, although it’s a bit more advanced in terms of features designed for managing remote employees.

With Google Drive, you need to get creative in terms of how you organize your files and set them up for business purposes. Dropbox has some of those tools built-in right out of the box (no pun intended).

Dropbox is a top option for those of you who need to share large files with remote workers. Team plans start at 5 TB of storage. You can send files up to 100 GB using Dropbox Transfer.

You’ll also have access to features like:

- Document watermarks

- Tiered administrative roles

- Single sign-on integration

- Ability to manage multiple teams

450,000+ businesses use Dropbox for managing files and content with employees.

With Dropbox, it’s an easy transition from the app to desktop. Your remote staff can start something on their computer and then access it on the road from their mobile device at a job site, client meeting, or anywhere else.

If Google Drive doesn’t quite meet the needs of your business, use Dropbox for an upgraded (but still very basic) workforce mobile app for content management.

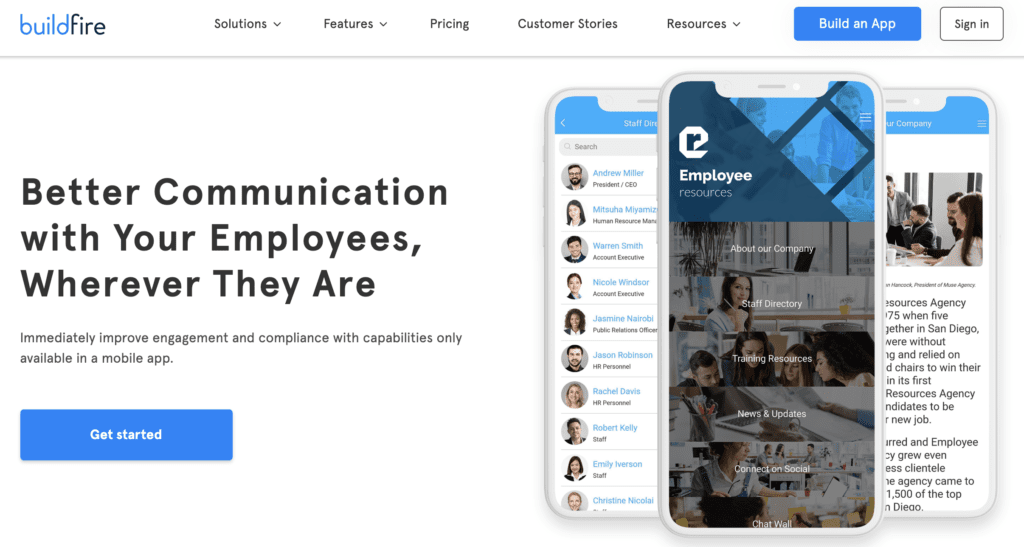

11. Build a Custom Workforce App

Rather than using a cookie-cutter solution with limitations, you can build a custom workforce app with BuildFire.

Custom app development gives you the opportunity to add whatever features you need to manage your mobile workforce. Instead of using one app for HR self-service and another app for internal communication, your custom workforce app can contain both features in a single solution.

Common use cases for BuildFire workforce apps include tools for human resources, safety, compliance, field service workers, and field sales workers.

Popular workforce management capabilities include:

- Employee training and development

- Compliance

- Company news and announcements

- Employee onboarding

- Real-time communication for a crisis or emergency

- Timesheets

- Time off requests

Custom app development gives you the ability to measure success and improve engagement with your mobile workforce. It’s also an all-in-one solution for to address challenges faced by your HR department.

BuildFire gives you the opportunity to create an app on your own. No coding or development experience is required.

For those of you who want some additional assistance with the development process, you can get the app designed and built by the team of experts at BuildFire. Our platform supports full customization.

Final Thoughts

There’s a common theme with the mobile workforce apps on this list. All of them have limitations and flaws.

Do you need an app for internal communication with remote employees? There’s an app for that. What about an app for managing projects and tasks? There’s another app for that. There are apps for video calling, file management, and field service employees. But none do all of the above.

The only way to get an all-in-one solution for mobile workforce management is with custom app development. Tools like BuildFire make it possible for you to manage employee tasks, real-time communication, payroll, self-service HR features, and more in a single app.

This is the best way to manage your mobile workforce and remote employees.