The way we communicate with and engage employees has changed drastically over the past decade. Companies are finding that email is no longer a viable option for all communication.

With many people using smartphones or tablets as their primary computing device, communication and engagement need to be convenient, timely, and personalized through mobile apps.

Do you need help with your employee engagement and internal communication process? Do you want to improve your employees’ communication and how they’re staying informed about what’s happening at work? Mobile apps can be an excellent solution for both of these.

This article will show you how a custom app can help your business build better internal communications and employee engagement by providing an overview of the possibilities. From company announcements to safety monitoring, compliance, and more, this post will make you rethink your current process. Let’s dive in!

1. Company Culture

A custom app can help build company culture by providing an exclusive space for employees to communicate and collaborate for their day-to-day lives at work. It also provides the opportunity of sharing important announcements or milestones with your team in real-time through push notifications right on mobile phones without having them waiting until everyone is back together again.

The modern workforce prioritizes happiness and lifestyle in the workplace much more than prior generations. If companies can’t create a culture that aligns with their employees’ values, those businesses will struggle to retain top-level talent.

Apps give that opportunity to do so. A custom app is a chance for human resources and leadership teams in your company to have conversations with remote employees, field service workers—even other use cases like managing their safety or compliance issues on the job site while they continue working. It’s also an awesome way of building up loyalty among current staff by showing them you care about what matters most— them! This translates into happier, more engaged people who will be eager to share good vibes around the office.

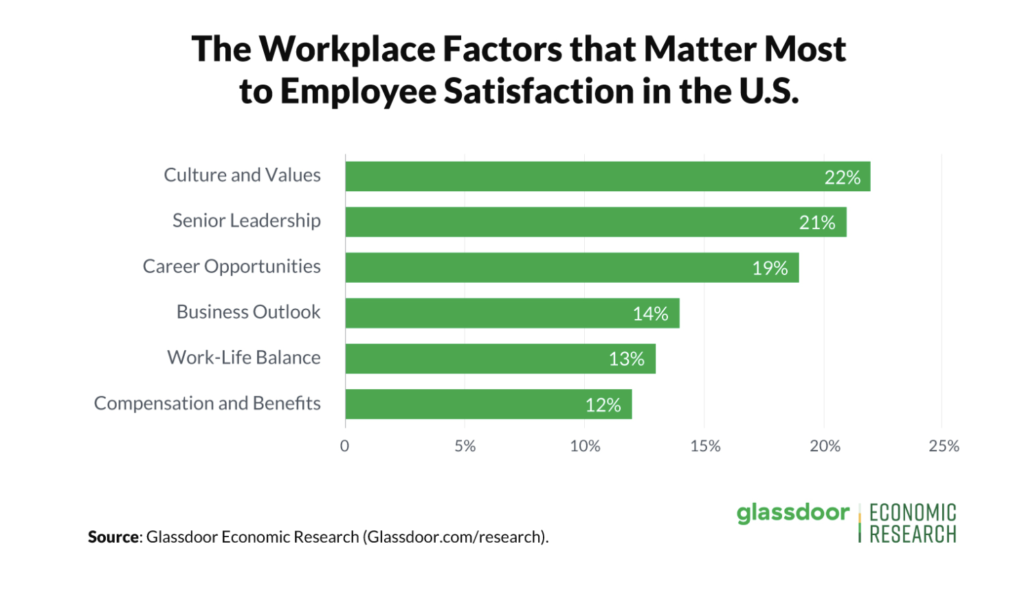

According to a recent study, company culture is the largest predictor of employee satisfaction in the United States.

You want top-level talent? Apps are how we keep people happy and loyal. Creating an internal apps is one of the easiest ways to improve the employee experience.

Practice what you preach and lead by example. Employee benefits, training, and team-building events are just a few ways to establish your company culture. All of this can be managed and improved with a mobile app.

2. Remote Work

Work from home has become the new normal. Even before a global pandemic turned the world upside down, remote work was trending upwards. More and more employees are working from remote locations, but they’re not as engaged because of isolation. Employees need a way to feel connected. Remote workers also want the tools at their fingertips to help them be more productive.

Remote work does have its benefits, like more flexibility, less time commuting (and saving gas money), improved quality of life by being closer with family and friends, and so much more. But remote work still creates problems.

People don’t have colleagues around them, and there’s no water cooler talk happening in the break room or at lunchtime with friends on their team because they work from home instead of an office building like everyone else does (or did). Employees need a way for coworkers not working remotely but still within your company network to stay connected as well—and it has nothing to do with staying safe during those pandemic days.

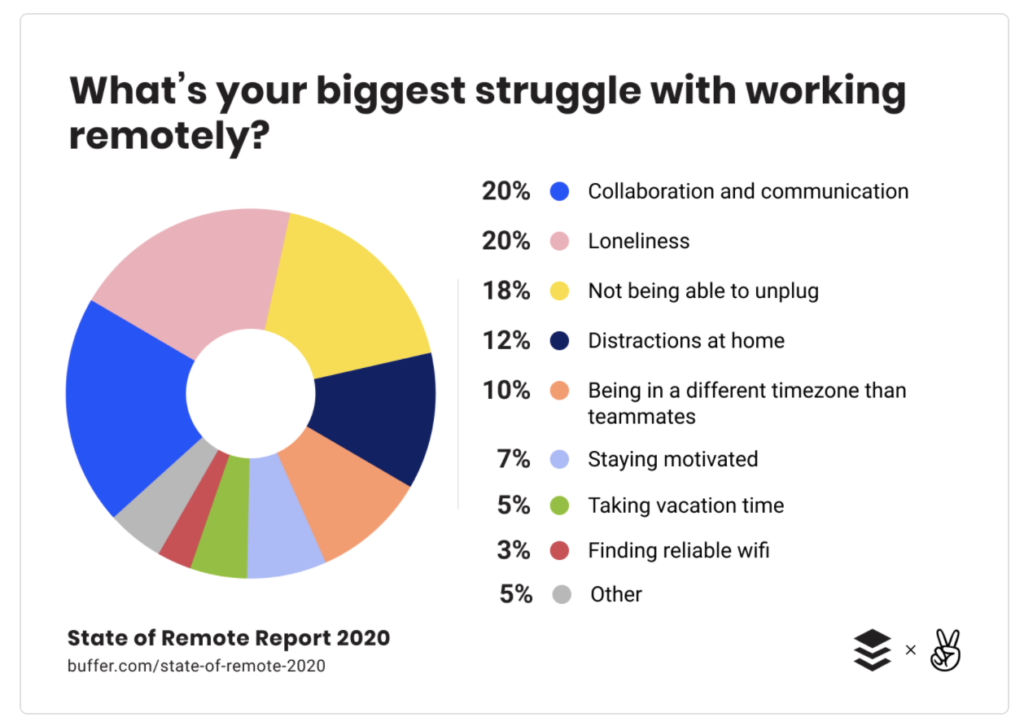

According to Buffer’s State of Remote Work report, collaboration and communication are the biggest struggles for remote employees.

It goes beyond keeping employees in the communication loop–it’s also about uniting them with your company culture (as mentioned in our last point).

A custom mobile app for effective employee communication will connect you with deskless workers and people working from home, as well as contractors and freelancers supporting your team.

3. Speed

Instant communication is a must-have in the modern workplace.

It’s not enough for HR to simply provide a way of communicating with remote employees, field service workers, and others. Those same people need the ability to communicate quickly—and asynchronously if necessary without relying on email or phone calls alone (which is so outdated). With mobile apps and communication channels like Slack in place that allow instant messaging from one device directly to another, it becomes clear why these intranet communicators have become immensely popular during periods when everyone wants answers now.

Some questions are more urgent than others, and can’t wait until tomorrow morning. Most employees prefer quick chats versus talking at all times on the phone or responding to lengthy emails.

Plus, employees are so accustomed to this type of communication in their personal lives that the idea is just second nature.

Users have grown increasingly more comfortable with using mobile devices for work, especially when it comes to time-saving tools on a smartphone compared to relying solely upon email and traditional phone calls as before (which was oftentimes slow). Mobile apps help people get things done faster since they can do everything from one screen on their preferred devices.

4. Peer-to-Peer Communication

In addition to using mobile devices for work, employees are also increasingly turning towards peer-to person communication. Sending messages through an app is actually faster and more convenient than ever before. Companies can create their own custom apps that offer features such as instant messaging. These IMs allow users access from any location with an Internet or Wi-Fi connection—which means no matter where you’re at in your office setting, there will be a way of communicating. No need to have someone come out into common areas like lunchrooms every time they need something done quickly or always being tethered by email replies sent back and forth inside company emails.

Internal communication between peers can be more productive than communication from top-down management. Employees can get their day-to work much done much faster with the help of these messages—and even when they’re away, it’s easy to communicate using IMs.

There are many other benefits that come from communication apps for businesses too. Announcements will be seen as soon as possible and onboarding new employees becomes easier, and so much more.

This two-way communication also helps strengthen employee relationships, which improves your company culture (as we discussed earlier).

5. Gamification

Implementing a game-based learning process is a fun and creative way to train your employees.

Gamification is a technique that has been used successfully for years by companies like McDonald’s, Walmart, and Starbucks to motivate employees. The benefits of gamifying employee training programs are directly related to engagement.

Check out these eye-popping statistics about gamification in the workplace:

Everyone loves an added incentive. If your team doesn’t have some type of gaming experience already, they’ll be able to make up ground quickly with these resources. A company culture built on fun can go far when starting out new initiatives—but more importantly, create intrinsic motivation which lasts longer than external rewards such games provide.

A mobile app is the perfect way to implement these game-based processes.

Gamification is ideal for the onboarding process, as it provides more incentive for employees to watch training videos and go through compliance-related tasks. Apps can also keep track of the tasks that employees have completed with a progress bar to show them what they’ve accomplished.

In addition to new hires, you can use gamification on a daily basis for work-related tasks. This type of feature can create some friendly competition amongst your staff as well. They’ll be trying to win different competitions and climb the leaderboards, which will keep them more engaged and ultimately make them work harder.

The best part is, gamification doesn’t require any additional training for your team. It’s something easy and fun you could start doing today.

4. Video Engagement

Videos are a great way to get employees engaged with the company and feel more connected. It can also help build a culture within an organization because it provides people opportunities for laughter, learning new skills, or being inspired by others who are excelling at their work—watching other videos on topics such as sharing best practices in your line of business. This concept applied while working remotely may make distributed workers feel better about not having face-to-face contact every day, which would increase productivity further downline.

Video content in a mobile app could be used for safety training programs, onboarding process improvement initiatives, consulting services advice sessions from experts outside organizations, and so much more. In addition to the quick and easy accessibility to this content, videos can also ease employee anxiety.

The key to a business success, from a communication tools perspective, is providing the users with what they need, when, and how. You can even include videos with detailed instructions and tutorials for field service workers to access on job sites.

Employees are used to consuming video content via mobile in their personal lives. From social media platforms to browsing YouTube, this has become second nature for most people. So the idea of adopting the same practices for an internal business mobile app won’t seem so foreign to them. In fact, most people will embrace it with open arms.

5. Measure KPIs For Effective Employee Communication

Without an internal communication app for your business, it can be difficult to understand the effectiveness of your communication strategy. How well is your company communicating right now? It’s tough to provide a concrete answer if there’s no way to track performance.

But with an app, you can see exactly how many employees are opening push notifications or how many of them have completed video training.

An app can help measure the KPIs that will contribute to a successful and thriving company culture. Once you’re able to measure the effectiveness of your internal communication, you can set benchmarks and target goals to continuously improve efficiencies.

This is a great way for companies that have remote employees or field service workers, as well as those with other needs like managing company news.

6. Apps Establish a Sense of Normalcy

Your employees are using mobile apps on a day-to-day basis for countless things in their personal lives. From online shopping to banking, social media, travel, and so much more—it only makes sense to give them this same opportunity to use an app in the workplace.

HR communication with a remote employee or field service agent outside the office won’t feel so “corporate” if messages are delivered via mobile. Plus, not every worker has access to a computer 24/7. But their phones are never more than an arm’s reach away.

Mobile communication apps can provide a central hub for company announcements or even an employee social wall or news feed for a more relaxed communication strategy. These types of features mirror the ones they use in their personal lives on other apps, which will ultimately drive more employee engagement.

All of these reasons contribute towards successful organizations where people feel valued.

7. Employees Become Brand Ambassadors

Younger generations crave authenticity in the workplace. They want to work for a business that puts them first and gives them opportunities to succeed.

By providing your staff with modern solutions like a mobile app for internal communication, it empowers their careers.

You can even use an app to facilitate employee-generated content. This will create more buzz around the office, and it’s more likely to get read and shared than news from management.

Employees are more likely to refer friends and family if they’re happy in their work. They’ll be ambassadors for the company, spreading positive word-of-mouth that will help make your business grow exponentially. Happy employees will care more about their jobs and do whatever it takes to bring your company to the next level.

Conclusion

A mobile app can help businesses improve internal communications and employee engagement. Mobile applications are more personalized to the needs of employees, which helps them be happier in their jobs, so they’ll care about performing better for your company.

Apps also give companies an opportunity to engage with employees on a deeper level that’s difficult using other channels like email or phone calls alone.

Ready to take your company to the next level? Starting building an internal communication app today with BuildFire—no coding required. Check out our workforce solutions to learn more about what you can accomplish with our platform.