Mobile app development has become a crucial component of the digital landscape in recent years. However, it’s not enough to just release an app to the public. App testing is a crucial step in the development process to ensure that your app is functional, user-friendly, and ready for distribution.

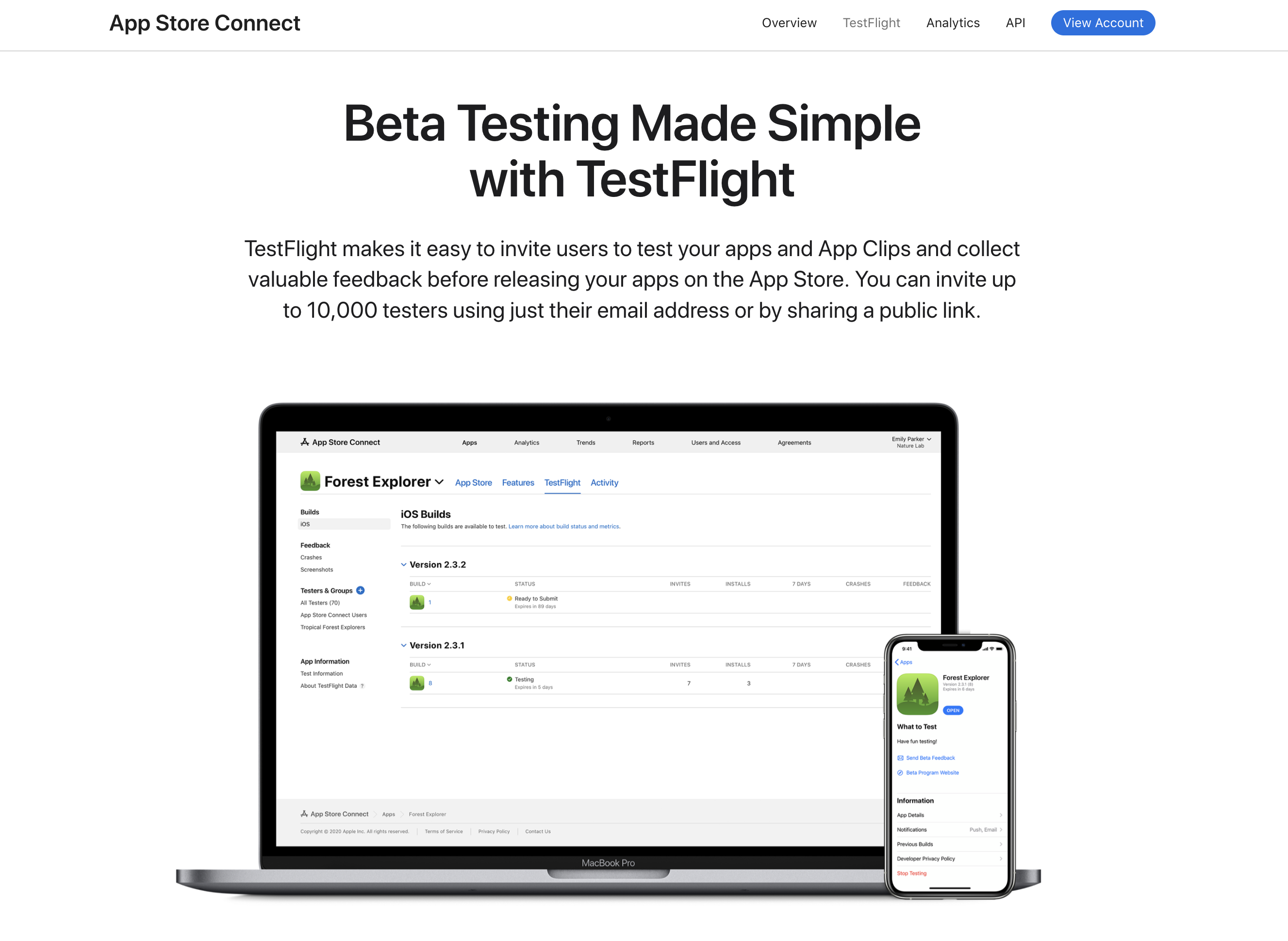

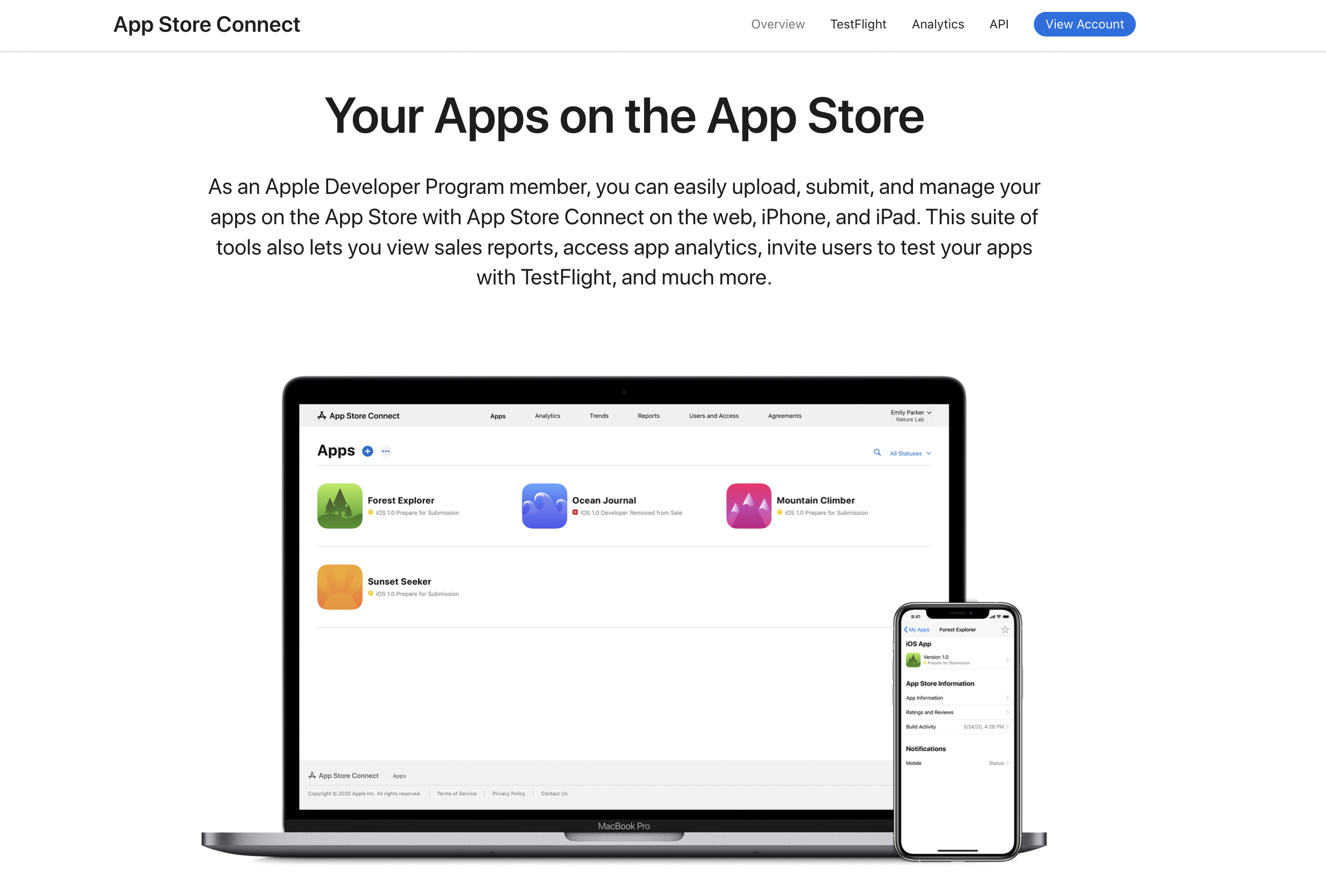

One of the most popular tools for testing iOS apps is Testflight—a free tool provided by Apple that allows developers to distribute apps to beta testers. With Testflight, developers can identify and fix issues, ensure compatibility with different devices, and improve user satisfaction.

In this blog post, we’ll provide a comprehensive guide on how to use Testflight for your app testing needs. From setting up a Testflight account to analyzing test results, we’ll cover everything you need to know to ensure your app is free of bugs and glitches before release.

We’ll also share best practices for Testflight testing and discuss common mistakes to avoid. By the end of this post, you’ll have a solid understanding of how to use Testflight to make your app the best it can be.

Setting Up Testflight

Before you can start using Testflight for app testing, you need to set up an account. Here’s a step-by-step guide to get you started:

- Sign in to your Apple Developer account. If you don’t have one, you’ll need to create one.

- Once you’re signed in, navigate to the “Testflight” section of the account dashboard.

- Click on the “Start Testing” button to create a new app in Testflight.

- Fill in the required information, including the app name, bundle ID, and primary language.

- Choose whether you want to upload a build of your app or create a new build using Xcode.

- If you’re uploading a build, drag and drop the build file into the Testflight window. If you’re creating a new build, follow the on-screen instructions to build and upload your app.

- Once your build is uploaded, select the “Internal Testing” option to invite testers to try out your app.

- Add testers by entering their email addresses or by sending them an invitation link.

- Choose the version of the app you want to distribute to testers, and then click “Start Testing” to send out invitations.

That’s it! You’ve set up your Testflight account and invited testers to try it out.

Testflight Roles (and How to Assign Them)

Here’s a closer look at the different roles available in Testflight:

- App Manager – Responsible for managing the app’s builds, testers, and testing groups. Managers can upload builds, invite and manage testers, and assign build access to specific testing groups.

- Tester – These users test the app and provide feedback. They can install and test the app, submit feedback, and report bugs to the app manager.

- Developer – This role is responsible for building the app and managing its development. They can upload builds, view app analytics, and manage testing groups.

To assign roles in Testflight, follow these steps:

- Navigate to the “Users and Roles” section of the Testflight dashboard.

- Click on “Invite User” to add a new user.

- Select the role you want to assign to the user.

- Enter the user’s name and email address, and then click “Send Invitation.”

- The user will receive an email invitation to join your Testflight team. Once they accept the invitation, they’ll be able to access the app and start testing.

By understanding the different roles available in Testflight, you can effectively manage your team and ensure that everyone is working together towards the same goal—creating an app that’s ready for release.

Uploading Builds

In app development, a “build” refers to a version of the app that has been compiled and prepared for testing or distribution. Uploading builds to Testflight is an essential step in the app testing process, as it allows developers to share their app with beta testers for feedback and bug reporting.

Here’s what you need to know to successfully upload builds to Testflight:

- Archive your app in Xcode – Before you can upload a build to Testflight, you’ll need to archive your app in Xcode. To do this, select “Product” from the Xcode menu and then click “Archive.”

- Export the build – Select the archived build in the Organizer window. Click “Export” and then select “Export for iOS App Store Deployment.” Follow the on-screen instructions to export the build.

- Upload the build to Testflight – Log in to your Testflight account, select the app you want to upload the build for, and then click “Add New Build.” Drag and drop the exported build file into the Testflight window.

- Choose the appropriate build type – When uploading a build to Testflight, it’s important to choose the appropriate build type. Testflight offers three types of builds—development, beta, and release. Development builds are for internal testing only and should not be distributed to external testers. Beta builds are for external testing and should be used for testing new features and functionality. Release builds are the final version of the app that will be released to the public.

- Provide build information – Once you’ve uploaded the build, you’ll need to provide information about it, including the build version, release notes, and app store information.

- Submit the build for review – Now that you’ve provided all the necessary information, you can submit the build for review. Testflight will review everything to ensure that it meets Apple’s guidelines and is ready for distribution to testers.

By following these steps, you can upload your app builds to Testflight and start testing your app with beta testers.

Pro Tips and Best Practices to Ensure a Smooth Build Upload

Here are some tips and best practices for uploading builds to Testflight:

- Test your app thoroughly before uploading to Testflight to minimize the risk of encountering issues during the build upload process.

- Make sure that you’re using the correct version of Xcode to avoid any compatibility issues.

- Uploading builds can take some time, so it’s important to verify that you have a stable and reliable internet connection.

- Create a separate folder for each build to stay organized and avoid confusion. This will make it easier to manage multiple builds.

- Provide detailed release notes to help testers understand what changes have been made in the new build and what they should focus on during testing.

- Use descriptive version numbering to track changes and identify specific builds.

- Keep the app size in mind. Testflight has a 200MB limit on the size of the app file, so make sure that your app is optimized for size before uploading.

- Before submitting a build for review, make sure that your app meets Apple’s guidelines for content and functionality.

- Use analytics to track app performance. Testflight offers built-in analytics tools that can help you track app performance and identify areas for improvement.

- Invite a diverse group of testers to help you identify issues that may not have been caught otherwise, such as device-specific issues or problems with non-native languages.

- Make sure to respond to feedback and bug reports from testers in a timely manner. This will help to build trust and ensure that your testers remain engaged throughout the testing process.

All of these pro tips will streamline your testing process and ensure the final product functions as desired.

Analyzing Test Results

Once the beta testers have had a chance to use your app, you’ll be able to view feedback and reports in Testflight.

Testflight provides several metrics to help you understand how your app is performing during testing. These metrics include crash reports, app launch metrics, and user engagement metrics.

Crash reports are important for identifying the root cause of crashes and bugs in your app. Testflight provides detailed crash reports that can help you identify the cause of crashes and prioritize fixes accordingly. User engagement metrics can help you understand how users interact with your app during testing. These metrics include user retention, session length, and user flow.

Once you’ve analyzed your test results, it’s important to take action based on the data. This may include fixing bugs, improving app performance, or making changes to the user interface.

Keep the following best practices in mind while you’re analyzing Testflight results:

- Segment your data – Segmenting your data can help you gain a deeper understanding of how different user groups are interacting with your app. For example, you can segment your data by device type, location, or user type to gain insights into how different users are experiencing your app.

- Compare data over time – Comparing your data over time can help you identify trends and patterns in user behavior. This can be especially helpful in identifying issues that may not be immediately apparent.

- Use heatmaps – Heatmaps are a visual tool that can help you understand how users are interacting with your app. Heatmaps can show you where users are tapping, scrolling, and swiping, which can help you identify areas where users may be experiencing issues.

- Use A/B testing – A/B testing is a powerful tool that allows you to test different versions of your app to see which one performs better. This can help you make data-driven decisions about how to improve your app.

- Seek feedback from testers – Testflight provides tools for collecting feedback from testers, which can be a valuable source of information for improving your app. Make sure to encourage your testers to provide feedback and take their feedback into account when analyzing your test results.

By following these tips, you can gain a deeper understanding of how users are interacting with your app during testing and identify areas for improvement. This can help you create a better user experience and ensure the success of your app.

Best Practices For Testflight Testing

While Testflight can be a powerful tool for app testing, it’s important to use it effectively in order to get the best results. Here are some best practices to keep in mind when using Testflight for app testing:

Here are ten best practices for managing and improving your app testing process with TestFlight:

- Create a clear and detailed test plan before beginning testing to help you stay organized and ensure that you test all of the app’s features thoroughly.

- Use a version control system to track changes to your app’s codebase. This will make it easier to identify issues and roll back changes if necessary.

- Always keep your app’s documentation up-to-date, including user manuals and release notes. This will help testers better understand how to use the app and provide more accurate feedback.

- Use a bug tracking system to manage feedback and bugs reported by testers.

- Regularly communicate with your testers to keep them informed and engaged about the testing process and upcoming changes.

- Provide detailed instructions for testers on how to submit feedback and bug reports. This helps ensure that you receive useful and actionable feedback from your testers.

- Continuously monitor your app’s performance during testing using TestFlight’s analytics tools.

- Schedule regular testing sessions with your team and testers to review progress and identify any outstanding issues.

- Always test your app on a variety of devices to ensure compatibility with different hardware and software configurations.

- Maintain a positive and supportive relationship with your testers. Showing appreciation for their work and keeping them engaged will ensure that they continue to provide valuable feedback throughout the testing process.

By following these best practices, you can improve your app testing process with TestFlight and increase the chances of launching a successful app.

Final Thoughts

Testflight is an incredibly useful tool for developers who want to ensure that their apps are ready for release. By inviting beta testers to try out their apps, developers can identify issues, gather feedback, and improve the user experience before the app is released to the public.

Testflight provides several powerful tools for analyzing app performance and identifying areas for improvement, including crash reports, user engagement metrics, and heatmaps. Using these tools can help you gain valuable insights into how users are interacting with your apps while simultaneously identifying areas for improvement.

From creating descriptive release notes to segmenting your data for analysis, the best practices described in this guide can help you get the most out of Testflight to ensure that your app is the best it can be. Our proven tips can help you streamline your testing process, improve the user experience, and release an app that’s ready to take the world by storm.