Building an app is a big deal.

So you should feel proud of your accomplishment.

Time to sit back and relax, right?

If only it were that easy.

Developing an app is only the first step if you want to actually make money.

You’ve still got to get your app approved and find a way to get potential users to download it.

Getting downloads is much easier if your app is ranked high in the Google Play Store.

But how do you improve your ranking?

Similar to the Google search algorithm for websites, we don’t know the exact weight of each factor.

However, we do know that there are certain things you can do to improve your app store optimization strategy.

I’ll discuss the main components of the app store optimization that will improve your app’s Google Play Store ranking.

As an industry expert, I’ve launched several mobile apps on the Google Play Store myself.

I’ve also helped numerous companies get their app off of the ground.

So I know which strategies work and which ones won’t lead to success.

Luckily for you, this is the right place to find out how to make improvements that will boost the overall perception and performance of your new app.

How to Rank App in Play Store – App Ranking Factors

Android users and iOS users behave differently.

So if you’ve previously had an app ranked on the Apple App Store, you can’t necessarily apply the same formula here.

Sure, there are definitely some similarities between the two ranking systems.

But if you want a high rank on the Google Play Store, you’ll need to follow the guide I’ve developed for you.

Here’s what you need to know.

Comprehensive App Store Listing: Google Play Store Optimization

Google says that your comprehensive store listing is critical in relation to your app’s discoverability.

It consists of these main components:

- App Title

- App Description

- Promo text

- Relevant Keywords

Your Google Play Store listing all starts with the app title. The app’s title is the first thing someone sees when your app appears on the screen and app stores page.

Coming up with a title that is clever as well as searchable is key.

Here’s the thing, for most of you the title of your app is already set.

If you have an existing business, your app will have the same name.

But you can make a minor change to make it more searchable.

Here’s an example of Delta’s app accomplishes this.

They named the app Fly Delta, as opposed to just Delta.

That way the title is more searchable.

If someone’s looking to book a flight, what are some words that they’re going to search for?

“Fly” is definitely a viable option.

So while you don’t need to completely change your app’s name from the name of your company, you can make subtle alterations.

Refer back to the main components of your comprehensive store listing.

Keywords play a factor.

We’ll continue to discuss the importance of keywords throughout this guide, but that’s a perfect example of a keyword used in the title.

Here are some other tips to consider when selecting a title for the Google Play Store.

- Try to make it as unique as possible.

- Do not use common terms or phrases.

- Reference and reinforce what your app does.

- Keep it short.

- Do not intentionally misspell common words.

Let’s use an app like TouchTunes as an example.

Their app allows Android users to control the jukebox for different locations across the country directly from their phones.

But take a look at the title.

It hits the mark for everything on our list above.

It’s unique without using any common terms.

The name is also short and concise, but you can tell that it has to do with music.

TouchTunes also didn’t use any incorrectly spelled words.

For example, here’s what would happen if they named it something like “TouchToones” in an attempt to be creative or unique.

The Android user searching for something on the Google Play Store would likely see their device autocorrect the spelling in the search bar.

So the app wouldn’t be a top hit in the search results.

This would definitely have a negative impact on the ranking.

Now that your title is all set, it’s time to focus on the description.

Here’s your chance to explain what users will get out of your app.

The Google Play Store will allow you to put in some keywords that help with search optimization in your description.

However, if you try to go overboard they will consider it “keyword spamming” and potentially remove the app.

Your description also can’t include anything that Google considers restricted content.

Examples restricted content on the Google App Store include:

- Violence

- Gambling

- Hate Speech

- Harassment or Bullying

- Sexual Content

- Illegal Activity

You’re also not allowed to deceive users in the description of your app.

Don’t lie and say that your app does something that it doesn’t.

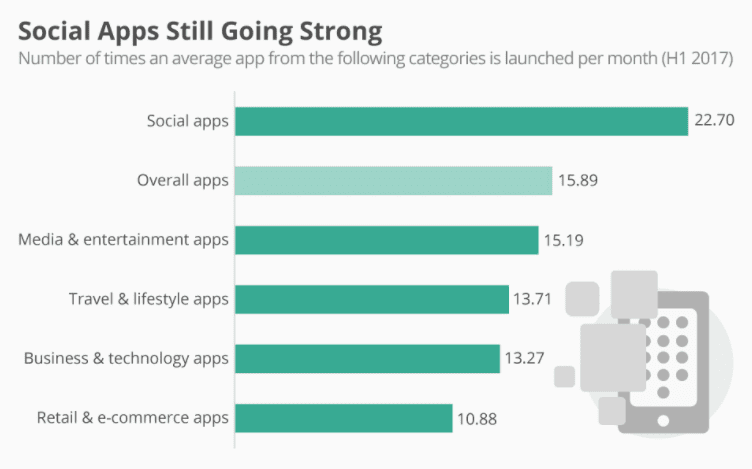

For example, just because social apps are popular, you can’t say that your app falls under that category just to get more app downloads.

Your description can’t impersonate another app, brand, or business.

You’re also not allowed to use anyone else’s intellectual property when writing a description.

The Google Play Store has you create promo text.

It’s a quick description that’s only one line long.

This only appears in older versions of Android software.

Look and Feel Graphics of Your Google Play Store App

You’ll need some high quality graphics to boost your ranking on the Google Play Store as well.

These graphics include your:

- App Icon

- Images

- Screenshots

All of these can help your app stand out when the search results come up.

The app icon should be bright, compelling, and inviting.

Don’t go with a generic color scheme.

Try to find something that will get the user’s attention.

This will help you get more downloads, which impacts your ranking.

I’ll go into more detail about the download rate shortly.

Here’s a great example of a bright and unique app icon from Slack.

You also need to include screenshots so prospective downloader can get a feel for how your app looks.

The screenshots should highlight your top features and key benefits.

Here’s a great opportunity for you to show off your differentiation strategy.

What makes your app unique?

How does it make life easier for the user?

Venmo does a great job with this.

They show multiple screenshots that depict the user experience.

Just from these few pictures we can see that the app lets you:

- Pay with both debit or credit cards

- Pay using a Venmo balance

- Request payments

- Split costs with several people at the same time

- Write a description about the payment

- See a news feed of transactions between your friends

It’s essential that your images are high quality.

In addition to Android phones, users may be viewing your app from a 7 inch tablet or even a 10 inch tablet.

If the image gets distorted on a bigger screen, it can negatively impact your download rate, which adversely affects your ranking.

Expand Your Audience

To get high search rankings, app developers must have diverse target audience.

However, you might encounter a problem with language barriers.

Google automatically has machine translations of all the listings in the Play Store.

You don’t actually define this for your own app.

With that said, you can still use a professional service that translates the features and description of your app.

At times, computer translations are inaccurate or don’t translate exactly the way the phrasing is meant to be heard.

But if your description is accurately translated from a human text translator via a 3rd party vendor, you can increase your chances of getting more hits all over the globe.

Here’s how you do it.

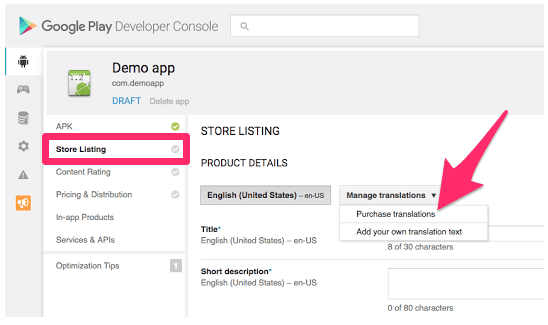

Go to your Google Play Developer Console.

From here navigate to the “Store Listing” tab.

Click on “Manage Translations” and then click “Purchase Translations” to proceed.

If you want to hire your own language expert, you can manually transcribe the text as well.

Personally, I think it’s much easier to just purchase the translations from a 3rd party vendor directly through Google’s platform.

It’s less effort, and it will help improve your ranking by exposing the app to a more diverse audience.

Your English keywords won’t be the same if someone is searching for this app in Italian.

Without sounding metaphorical, your words will literally be lost in translation.

User Experience

Lots of the topics that we’ve covered so far focus on the user experience.

Your mobile app needs to perform at a high level, or nobody’s going to want to use it or download it.

The download rate impacts the app store search results in the Google Play Store.

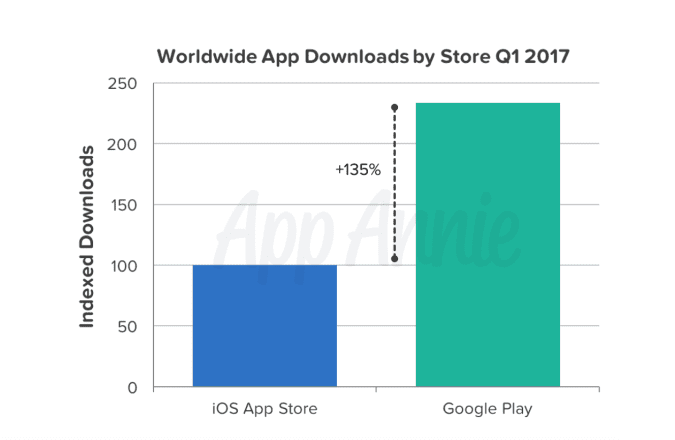

Releasing your mobile app on the Google Play Store was a smart move.

Take a look at the amount of downloads there are across the world on this platform as opposed to Apple’s iOS App Store.

The Google Play Store has 135% more downloads.

This should be encouraging, but also tells you that it’s competitive space.

Use your best marketing skills to promote your app and get more downloads.

If you have an existing business, you’re already at an advantage when it comes to this promotion.

Why?

You have marketing channels and customers already in place.

Reach to your email subscriber list.

Promote your app on social media.

Talk about it on your blog and website.

Your customers have likely been waiting for this app to improve their overall customer experience, so I’m sure they’ll welcome it with open arms.

The more downloads you can get at a fast rate will boost your search ranking.

But having a high ranking involves much more than just downloads.

You’ll need people to actually use your app.

Unless you’re charging for downloads, you won’t make any money if nobody is downloading the app.

But you also need users to review and rate their experience.

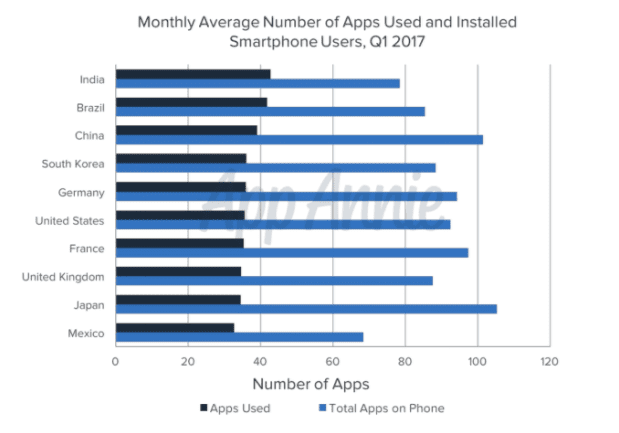

Take a look at how many apps people actually use.

The majority of time spent using mobile applications is only between three apps.

People won’t be able to leave a review if they’re not using it.

That’s why your app needs to satisfy the user.

If it’s not adding any value to their life or providing any entertainment, they have no reason to use it.

One of the best ways to get more reviews and ratings is by encouraging feedback and interaction with the users.

After they’ve had the app for a week or two, send them a notification asking for a review.

Otherwise, they might not go out of their way to rate it.

It’s all about providing excellent customer service as well.

If your app users have comments, complaints, or suggestions for the app’s performance, take those into consideration.

Come up with new versions of the app that fix any bugs or glitches.

People will only give you so much leeway before they decide to stop using your app.

You don’t want to be the app that someone downloads but never uses.

Look how staggering the results are on this graph.

If you can’t focus on improving the customer experience, your download rate, reviews, and ratings will all suffer.

But if you can master these components, it will boost your Google Play Store ranking.

Conclusion

The lifecycle of your app isn’t complete once you finish building it.

To be successful, you’ve got to get users to download it from the Google Play Store.

It’s easier for Android users to find your app if it’s ranked high on the Play Store.

To do this, you need to understand how the Google algorithm works and take the necessary actions to ensure your app hits all of the requirements.

Start with a strong title.

It should be short, memorable, and speak to the functionality of your app.

The app’s description is the best place for you to include keywords to boost its search optimization.

Just make sure that you stay within all of the guidelines set in place by Google.

Focus on images as well.

Include some screenshots that display exactly how your app works.

It will give a prospective downloader a chance to preview the app before they actually download it.

Come up with a colorful and creative app icon.

Doing all of these things will help improve your download rate.

The more downloads you get, the more ratings and reviews you’ll receive from users.

Cumulatively, this is a recipe for success to shoot your app to toward the top of the Google Play Store rankings.

What keywords will you include in your app’s description to improve its discoverability and app store SEO?