Company Profile

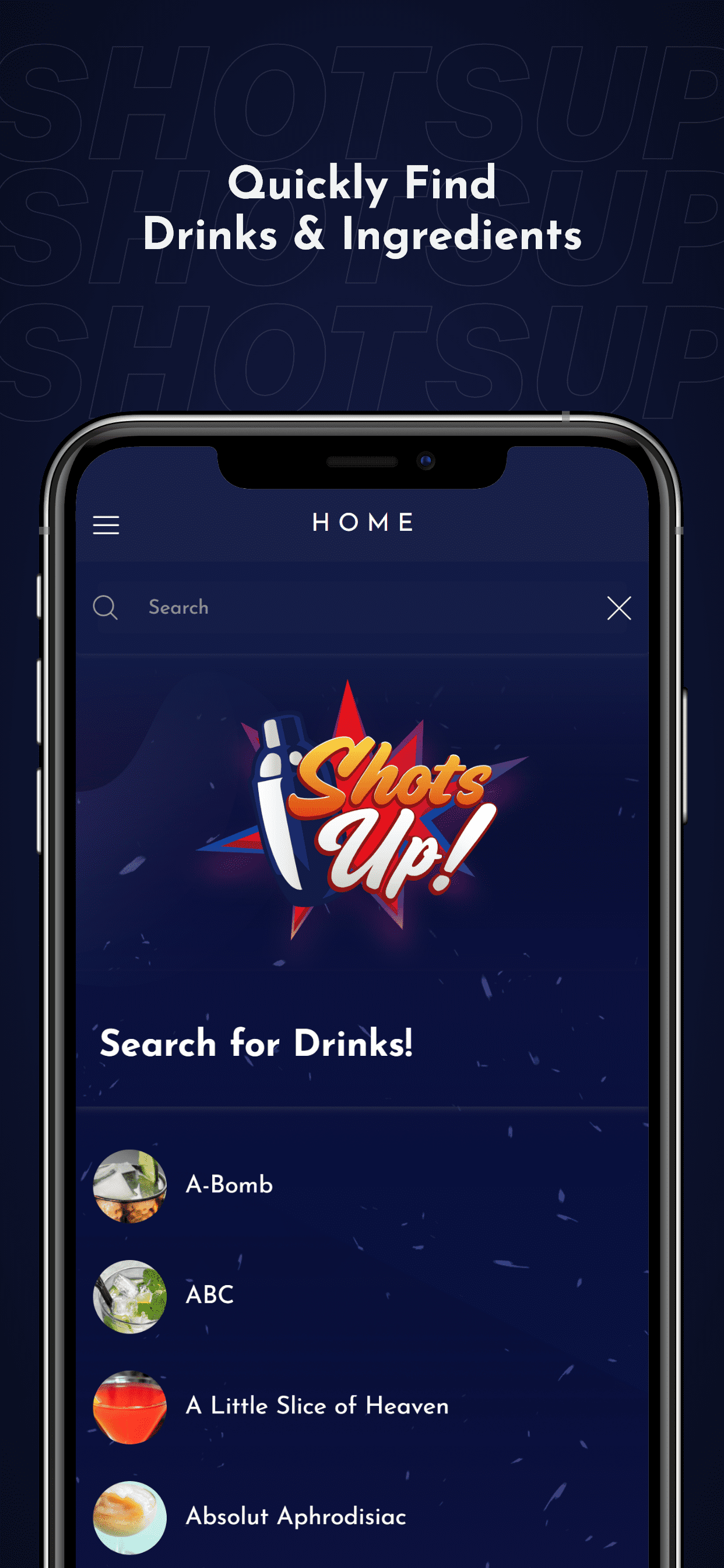

Shot’s Up is a must-have mobile app for bartenders and drink enthusiasts. Packed with hundreds of shooter recipes, it serves as a valuable reference for professionals and entertainment seekers alike. From nostalgic favorites to wild and seductive shots, the app provides a wide variety of options to spice up any occasion.

Recipes For Every Palette and Event

Covering a range of themes and events, Shot’s Up caters to diverse tastes. Whether you’re in the mood for patriotic shots, holiday classics, or tantalizing concoctions for bachelorette parties and wild gatherings, this collection has it all.

Discover new recipes that bring back memories and inspire unforgettable entertaining experiences.

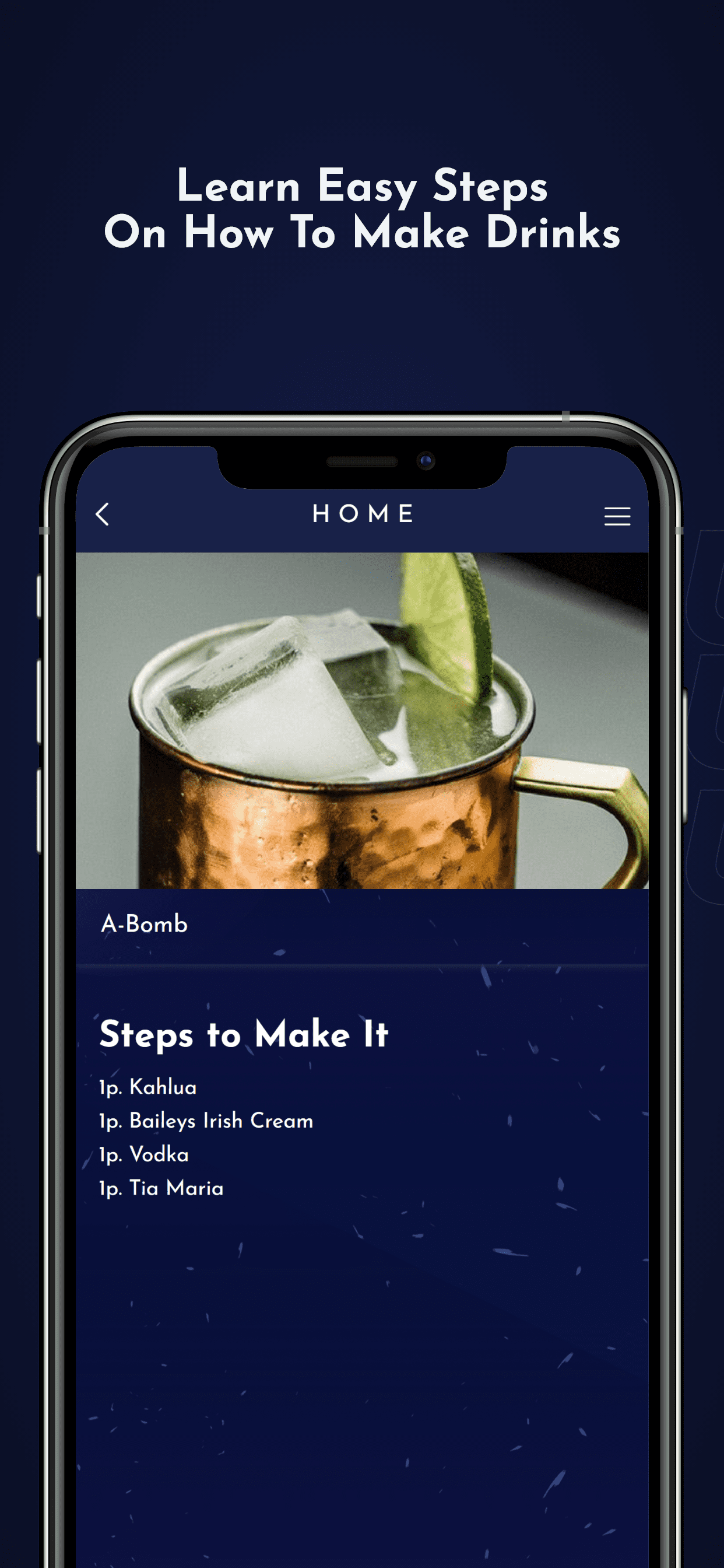

Unleash Your Creativity, Impress Your Guests

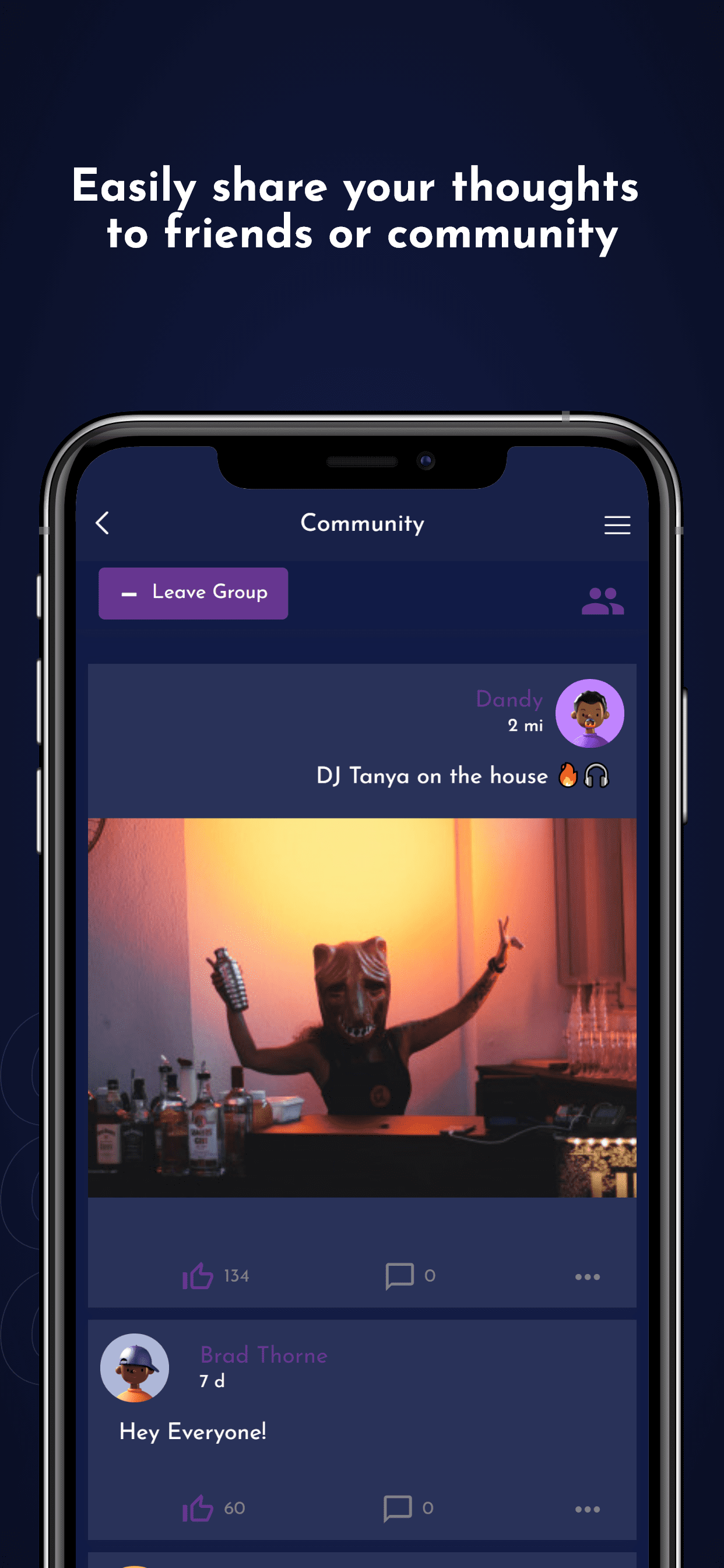

With Shot’s Up, the possibilities are endless. Tap into your creativity, experiment with flavors, and entertain in style.

Whether you’re a professional bartender or a casual host, this mobile app will help you concoct captivating shots that leave a lasting impression on your guests. Get ready to elevate your bartending skills and create memorable moments with Shot’s Up at your fingertips.

Cheers to the exciting world of shooter recipes!