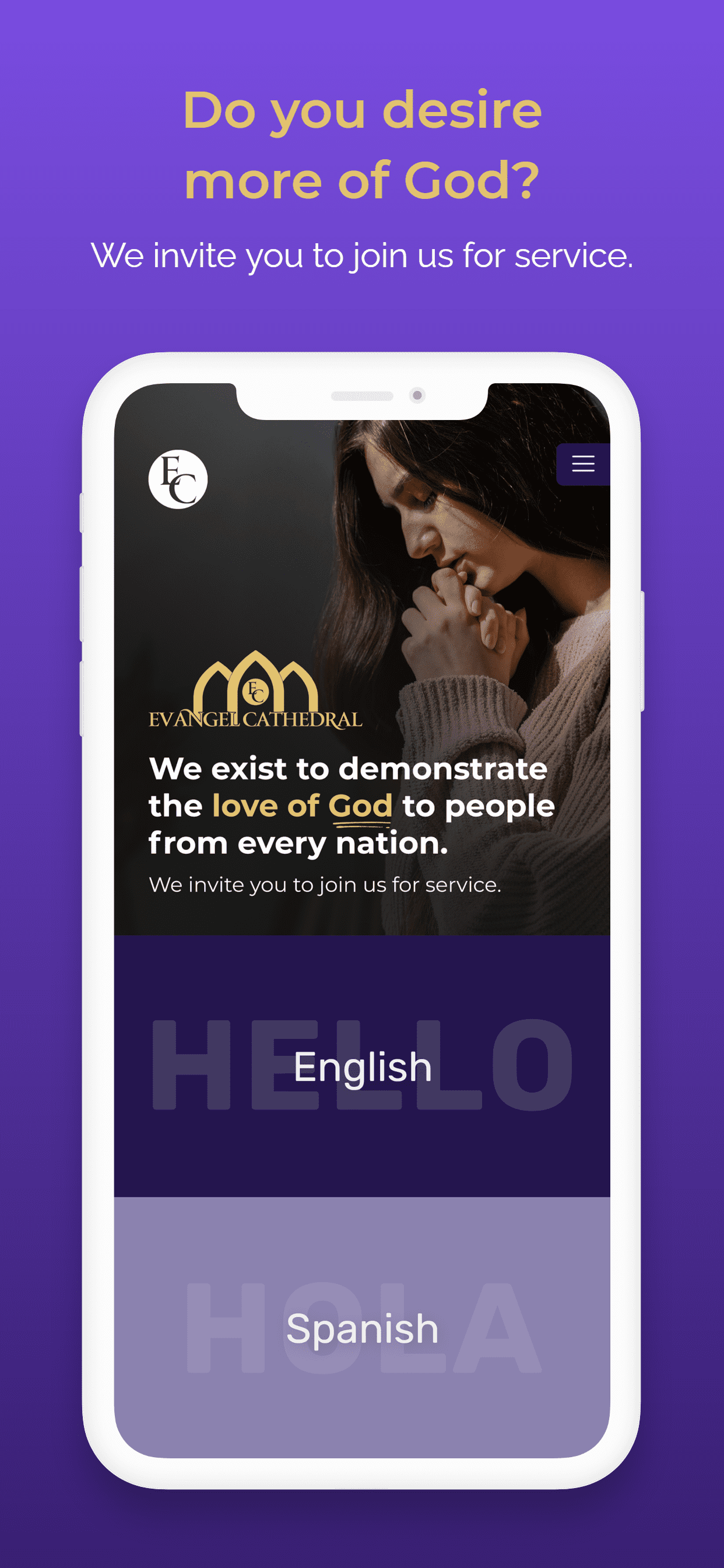

Client Profile

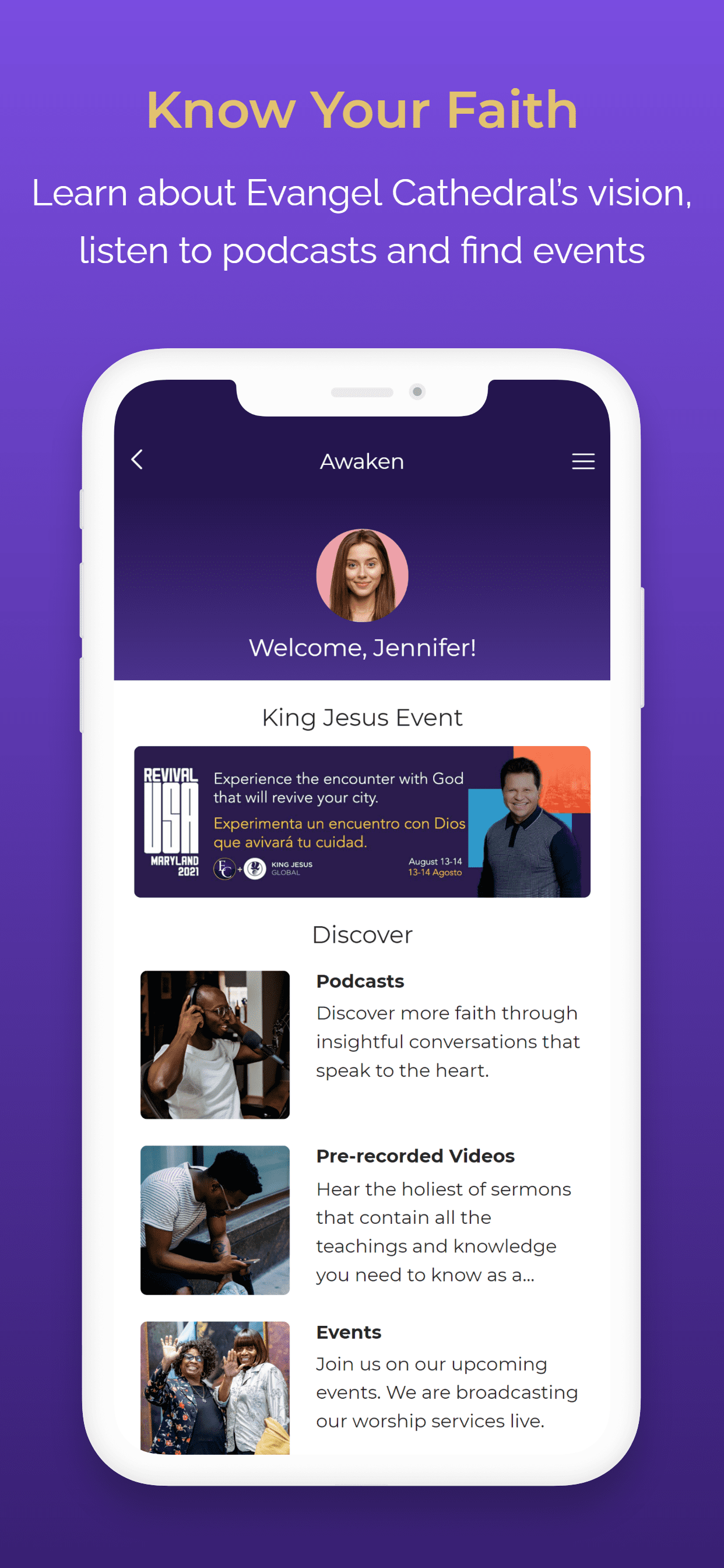

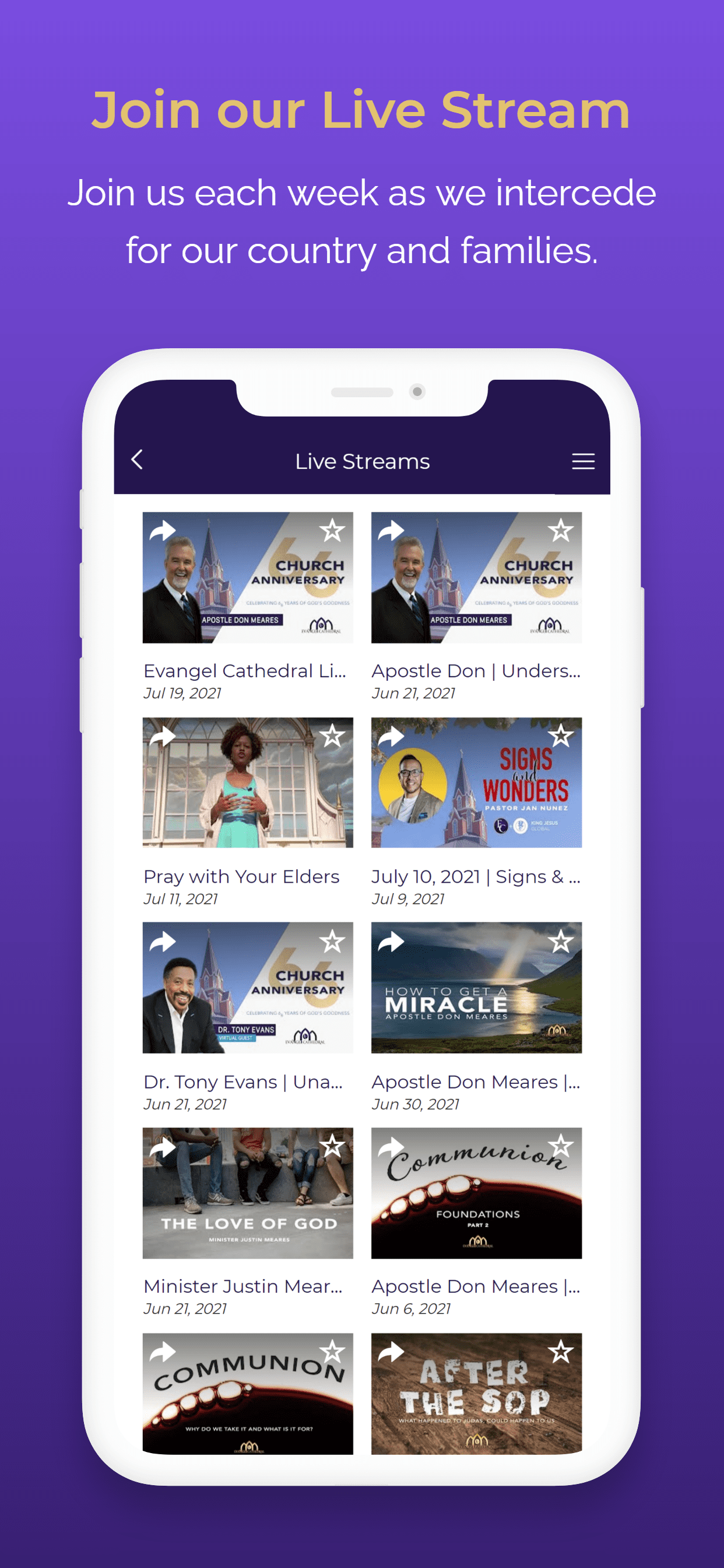

The Evangel Cathedral is located in Upper Marlboro, Maryland. With the Awaken app, members can join worship services, watch sermons, and access on-demand videos from anywhere, at any time. The app makes it possible to experience the power of the Evangel Cathedral and stay connected to its vibrant community from anywhere.

Prayer and Support

Deepen your prayer life with the Awaken mobile app. Engage in topic-based prayer videos for inspiration and guidance, or share your prayer requests to support others through the prayer wall.

Experience the strength of a united community, lifting one another up in prayer.

Inspired and Informed

Stay informed and inspired with push notifications and updates from Apostle Don Meares, First Lady Marion Meares, and the Evangel Cathedral leadership. The app sends timely announcements, event details, and teachings to ensure you never miss a beat. Awaken your potential and embrace a life of purpose and growth.