Success in business breaks down into two simple things:

- Can you supply something that people want at a price they’re willing to pay?

- Can you get your offer in front of those people?

Nine times out of ten, people start a business because they are capable, competent, or even brilliant at that first part. They know their industry and they are able to supply what people want.

The second part is where things get tricky. How do you get your offer in front of the right people? Or in other words, how do you promote your business?

Today, we’re going to be looking at # incredibly simple yet highly effective ways to promote your business. You can implement all of these quickly without needing special expertise or significant investment.

If you’ve been looking for new ways to reach your target audience, you’re in the right place.

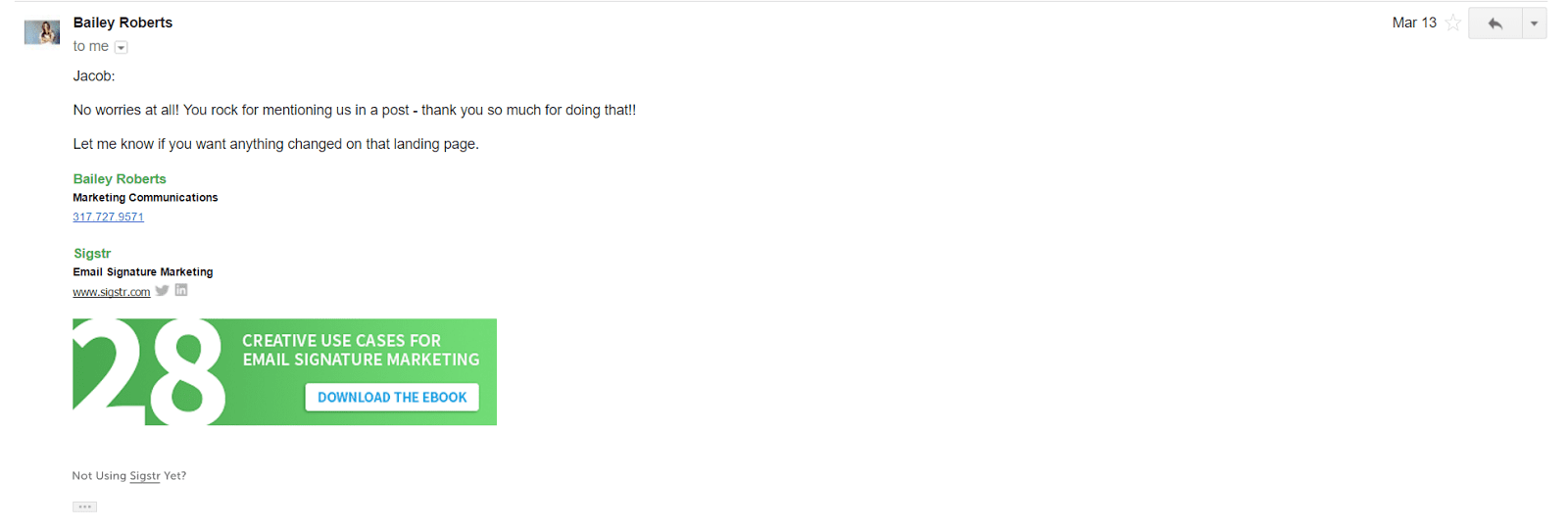

1. Insert Calls To Action In Your Team’s Email Signatures

The average office worker sends a receives 122 emails per day. For a business with ten staff, that adds up to around 600 outgoing emails per day.

These emails are actually a tremendous promotion opportunity, but not using traditional email signatures. Nobody is going to take notice of your employees’ job titles or websites. Nobody cares about your favorite quote.

What CAN get attention is a big obvious Call To Action button.

Notice how well this CTA stands out and attracts attention.

When you view email signatures as a marketing tool, they become dynamic ways of introducing your products or services to potential customers.

For a single email, you can simply set something like this up via your email client, but if you are interested in rolling it out across your entire team (most beneficial), you’ll want to use an app like Sigstr, which will let you manage signatures and rollout campaigns across your entire team at once.

The best way to take advantage of email CTAs is to offer some sort of lead magnet or freely available offer that will interest your target audience and push them forward in your funnel.

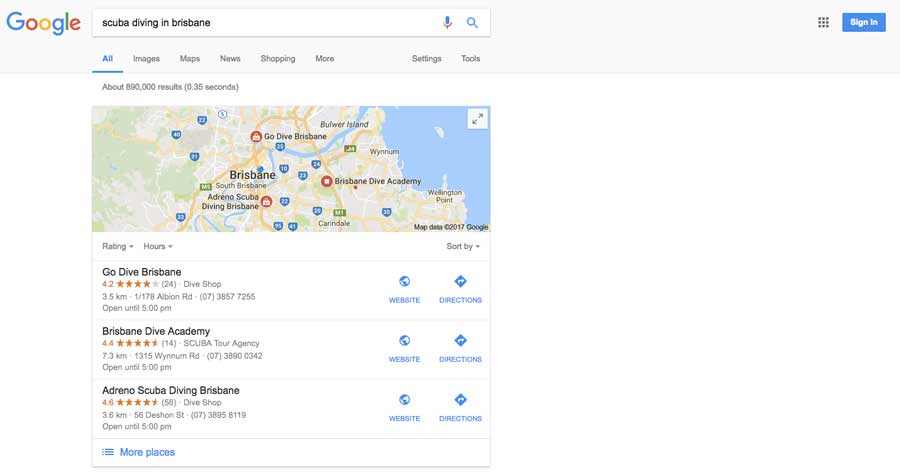

2. Set Up A Google My Business Account

Google is not only a search engine, but also a small business directory. Take advantage of these tools. Setting up a Google My Business Account provides three major benefits for companies who rely on local business:

- Your local business is listed on Google maps and search.

- It’s good for search engine optimization, so that your business gets found easier by the people who are looking for the services or products you provide.

- It’s good for when your customers start adding reviews of your business; these reviews help Google display your business in their “3-pack”, which gives you free advertising at no cost.

Google My Business Reviews have earned these companies the top spots in Google search results.

Your GMB listing is the baseline for all your online citations and listing, and it’s important that every listing matches your GMB listing, particularly when it comes to your three primary pieces of information, known as NAP (Name Address Phone Number).

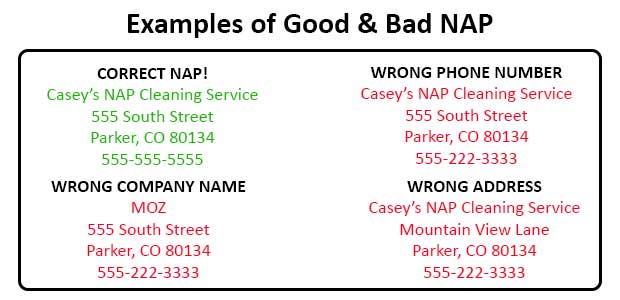

3. Audit Your Online NAPs

NAP stands for Name, Address, Phone number, also often referred to as citations.

Out of Moz’ top 6 “Foundational Ranking Factors”, (for search engine ranking), 3 are related to NAP quantity, quality, and consistency, and out of the top 13 “Competitive Difference Makers,” 6 are about NAP quantity, quality, and consistency.

If you’ve listed your company on Google My Business, you need to make sure the details there are the same for all your online listings.

Image Credit: Moz

If any of the details elsewhere are not the same as it is listed in Google My Business, then you might not be “rewarded” by search engines and it could also damage your search ranking.

A suggestion is to keep an Excel spreadsheet of all your listings, to make it easy to keep them consistent.

Moz offers in-depth information about NAP audits and how to do them.

4. Set Up A Joint Venture

As I mentioned earlier, promoting your business is all about getting your offer in front of the right people. One of the easiest ways to do this is to find existing audiences filled with the “right” people and simply place your offer in front of them.

In some instances, that can be done via advertising, but an even better option in the short term is to partner with non-competing businesses marketing to the same people as you are.

Joint ventures are a brilliant way of getting more customers fast. Take Teachable, which was started in 2014 by Ankur Nagpal. He says that 6 months into starting the business, they had less than 20 active customers making money from courses. In 2015, they created a joint venture which gave them more customers fast.

Nagpal lists a few examples of joint ventures they’ve since used in their marketing strategies, one of them being a simple affiliate partnership with marketer Melyssa Griffin. Teachable gave Melyssa a unique promotional tracking link plus 50% commission on every sale.

Melyssa Griffin, affiliate marketer and joint venture partner with Teachable.

Find out more about joint venture examples from the founder of Teachable, which now boasts a monthly growth rate of more than 20% in 2016, increasing its revenue tenfold in one year, with more than 1 million students.

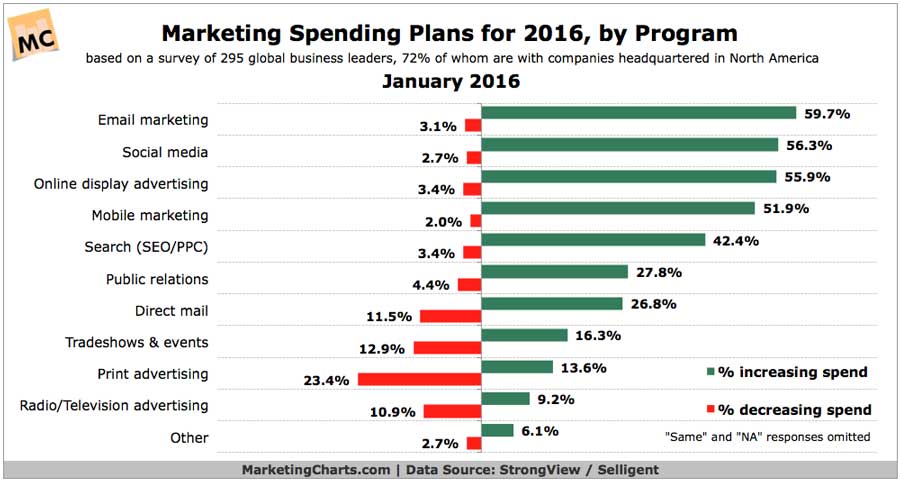

5. Create An Email Marketing Strategy

Email marketing is the cornerstone of online marketing.

From a technology standpoint, email has withstood the test of time as a communication channel. From a marketing standpoint, email converts at a higher rate than nearly any other channel.

As recently as 2016, email marketing was the leading marketing expense among global business leaders.

Email marketing allows you to nurture relationships with potential buyers over time. It allows to place visitors who aren’t ready to buy into a funnel that keeps them connected with your business instead of having them forget about you.

To begin taking advantage of email marketing, you’ll need to create something valuable that can be given away for free in exchange for a visitor’s email address. Digital info products are often best for this purpose.

Next, you’ll want to create a series of emails designed to introduce the new lead to your offer, establish your authority in the industry, and deliver educational value on related topics of interest.

To learn more, check out these fantastic email marketing examples.

6. Offer a Free Or Discounted Product/Service

In a similar vein to the lead magnets we just talked about, offering something free or at a discount is a great way to draw in new customers. Depending on your business model, it can even be effective to take a loss on this in order to pull in market share.

There are many iterations of this that can be used to drive leads, sales, referrals, etc. Ecommerce stores in particular have had amazing success with introductory discounts.

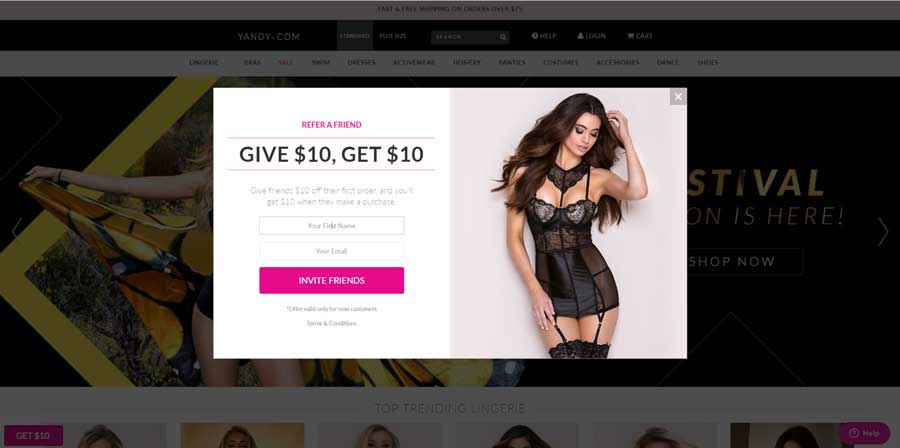

Here’s an example from lingerie e-retailer Yandy.com:

Other possibilities include free software apps or free trials. For example, BuildFire allows prospective customers to create an app for free, allowing them to experience the actual product before being required to pay anything.

7. Give A Presentation or Webinar

This strategy can be equally effective online and offline. By offering a webinar or workshop, you can attract your target audience and collect their contact information for future followup.

First locate where your target audience hangs out, then set up meetings. For instance, AwaiOnline recommends “Lunch ‘n Learn” sessions of one hour. Organize lunch and do some advertising to the right people, and then teach them something in one hour, over lunch. Try hosting it at your local Chamber of Commerce or other business networking groups.

Copywriter freelancer Steve Slaunwhite used online “Lunch ‘n Learn” sessions to promote his copywriting services to his target audience and said, “The Virtual Lunch ‘n Learns would get me in front of my target audience and position me as an expert at what I do. Of those who attended the teleconferences, some would decide to give my services a try. These were small numbers of prospects, but they were high quality. I got several leads and referrals and some very good clients by doing these sessions.” (Source)

Mary-Ann Shearer, health guru, whose vegan restaurant is located in an area known for its affinity for meat, educates people by holding talks for groups at gyms, running clubs, churches, etc. When she does, she gets email addresses from people that are already “sold out” to her, because within minutes, she is able to prove herself as an authority on her subject. When her presentation is over, she has collected well qualified leads; people who are sure to start buying products from her online store.

Mary-Ann Shearer conducting a group talk about natural health at a local gym.

If you don’t want to go the offline route, you could instead host a webinar or podcast interview (I recommend using PodMatch.com to quickly get booked on podcasts), or do a joint venture with a partner who hosts a webinar, as a way to collect email addresses.

Jeff Rose hosted a webinar on “How to Protect Your Investment Portfolio”.

8. Ask for Reviews

54% of people visit a website after reading positive reviews about the business, and 84% trust reviews as much as they trust a personal recommendation. (Source)

Reviews build trust and credibility for your business, and they carry a lot of weight. You can also use them on your website, specifically your home and about page. But that’s not the only thing reviews are good for. They also increase your search engine ranking, which results in increased website traffic. Why? Because search engines recognize the value of customer reviews.

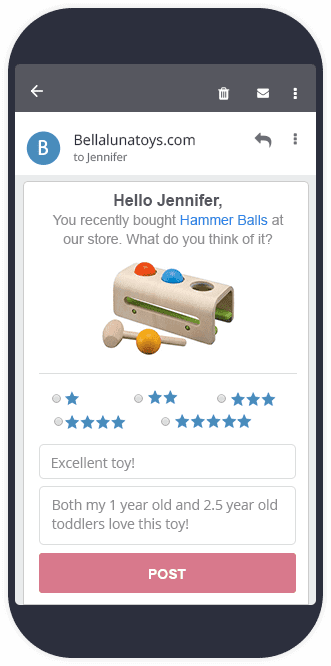

Bella Luna Toys, an ecommerce company, started using reviews on their website, and since doing so, their conversion rates shot up by 15%. They’ve also generated more than 4500 genuine customer reviews. (Source)

Bella Luna Toys have increased conversions by 15% since incorporating reviews onto their website.

To collect reviews, simply setup your Google My Business listing and other citations that take reviews, and then send the links to your customers with the request that they leave a review. Alternatively, you can use an app like Yotpo to collect written reviews or VocalReferances to collect video reviews as an automated part of your checkout system.

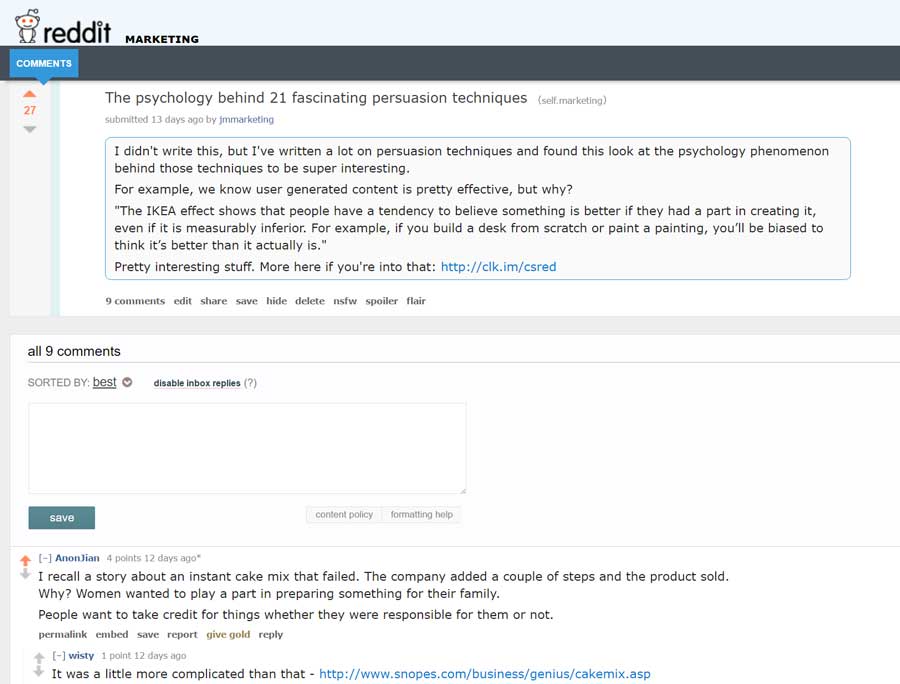

9. Comment on Blogs In Your Niche

Leaving a comment on other related blogs can help rank your content on search engines faster, because:

- Adding a link to your site from a comment on another site, gets Google and other search engines to pick it up, and if the website you’ve left a comment on, is reputable, search engines are likely to index your content with a higher ranking, because of your association to the website through the link left in your comment.

- If your comment adds value, it may get attention from a future customer who is so impressed by what you’ve written, that they click back to your website.

- Adding value-add comments on other blogs helps build relationships with bloggers and others in your niche, which may very well open doors to joint ventures.

Example of comments that are well written and add value to anyone reading them.

The image below is taken from a data analytics page and shows how backlinks from comments are counted, even if they are no-follow links.

10. Do “It” Better Than Your Competitors

Business are often started as an attempt to do something better than the existing marketplace. The same mentality is true for promotion.

When it comes to any marketing channel, usually the top marketer or two in that channel will captivate 90% of the competition. Instead of being middle of the road on multiple channels, it’s best to identify a channel where you can “do it the best” and pursue that channel.

For instance, an online academic book and technology business in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, wanted to increase their website visitors. A consultant was brought in who compiled a report showing what the worldwide benchmark company was doing, and these are some of the findings:

The benchmark company had a whopping 7394962 Facebook likes, with a 100% response rate, while the other company had a mere 5839 Facebook likes, and a 0% response rate. In addition, the benchmark company had tons of content and their product descriptions were customized.

When analyzing the online activities of a worldwide benchmark company, it was found that their differentiating factor was lots of value-add content.

Next, they checked how their top local competitors were doing online, and found that if they were to implement a content strategy, they could whip all the others in their area.

What they took home from the analysis:

- The need to start creating Facebook posts that would attract their target audience, and to start paying for Facebook ads to boost their Facebook page engagement rates.

- The necessity of responding quickly to social media messages from their customers.

- The need to start writing customized product descriptions.

- The importance of website content.

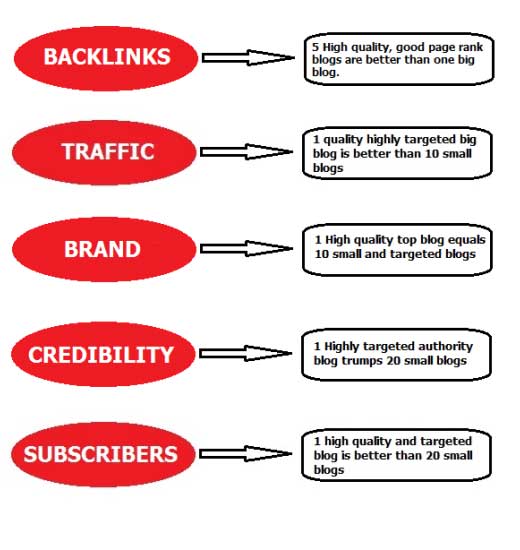

11. Write A Bunch Of Guest Posts

Guest posting is one of the most effective ways to promote your brand online.

Guest posting is where you can write an article for another website that they then publish and promote to their audience.

While guest posting will rarely drive any significant amount of actual traffic, it can be very valuable for a number of reasons:

- Establish yourself and your brand as an authority in the space

- Get backlinks to your website from popular, high-ranking websites

- Get your brand directly in front of your target market

- Network with influencers in your niche (potential joint venture partners)

- Link to people who will then link to you in their own guest posts

Silvio Porcellana is the CEO and founder of Mob.is.it. The company provides a tool which helps agencies and professionals build mobile websites and native apps.

When he realized that the website needed more organic search traffic (visitors brought in from search engine results), they decided to implement a guest blogging campaign.

Within 5 months, they published 44 guest posts on 41 different blogs. The result?

The website’s search traffic increased by 20%.

Here’s an illustration by Writers In Charge of why guest blogging is so effective:

12. Utilize Facebook Instant Articles

Facebook Instant Articles is a distribution platform where you can share content just like you would on your own website, or on Linkedin articles, but with interactive elements that enhance the mobile viewing experience. The content on Facebook Instant Articles is accessible to Facebook users on Android and iPhone devices.

It’s especially valuable if you want to build value, credibility and brand awareness. The benefits of using this function is:

- Fast load time. Facebook reports that Instant Articles has 70% lower bounce rates and 30% higher share rates than most of the web articles accessed via mobile devices.

- You can make money right from the platform with your own display and media rich ads and you also have the ability to display Facebook Audience Network ads if you so choose.

- You have control over your own branding.

- The platform allows integration with other measurement tools like Google Analytics.

- Interaction for a better reader experience.

- You can add content that’s already been published on your website, and there’s a plugin to make it all easier if you’re on WordPress.

Gray Television integrated local news with Instant Articles and generated $250,000 in revenue from the Facebook Audience Network.

Gray Television integrated Instant Articles with local news.

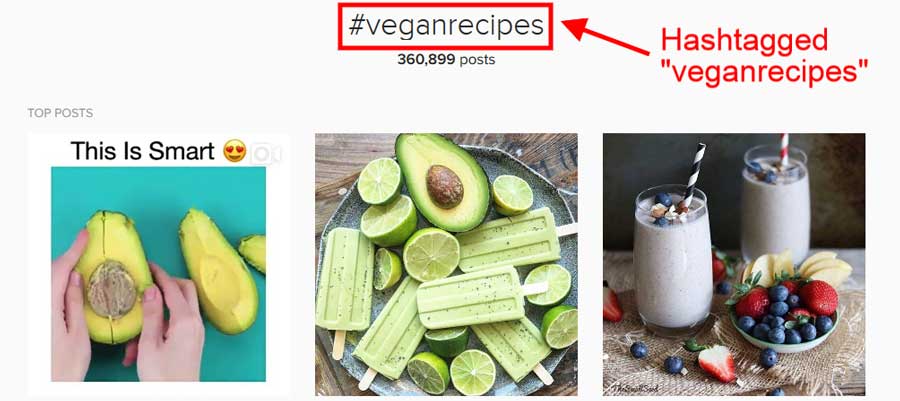

13. Use Visual Media To Build Your Social Media Presence

There are 2.3 billion active social media users. Whatever your target audience looks like, you can find them on social media, and visual content is one of the best ways to expand your social presence.

Here’s a good place to start:

- Create visual content that is relevant to your niche

- Use high quality images or video

- Get your customers involved

- Tap into trending hashtags and current events

In the beginning, before you have an audience of your own, it’s important to engage with people directly and tap into your target niche. One of the easiest ways to find these individuals is hashtags.

These are images that were uploaded to Instagram, all hashtagged, “veganrecipes”:

If you wanted to get in front of people in the vegan niche, finding out what people are talking about and favoriting around #veganrecipes would be a great place to start.

For more insights into this strategy, read this case study about how Fusion Farm used hashtags to promote an event.

14. Create Content That Attracts Your Audience

Some of the tops blogs in the world make an average of $15,000 to $30,000 a day.

People love consuming blog content online, and it’s highly unlikely your niche is exempt. In order to tap into that demand, you simply need to create content that attracts the same audience you wish to sell to.

For example, Glen Allsop, founder of PluginID, was a complete newbie in his field when he first started blogging. Because of adding great content to his site, his subscription list grew to 26,000 subscribers, many of whom also became customers, helping his business take off.

Glen Allsop’s internet marketing blogging content grew his subscriber list to 26,000 in a short timespan.

And just like we are giving you ways to promote your business, you will also need ways to promote your blog content.

15. Promote Your Content

Promoting blog content is a great way to build authority in your niche will also directly promoting your business. In fact, it’s one of the few ways you can get away with shamelessly promoting yourself. You can share blog posts is a lot more locations than you can directly advertise a product or service.

There are many, many ways to promote content, but here are some of the best ones I’ve tried:

- Send the content to your email subscribers

- Share it with your social followers

- Share it on Reddit and other community sites

- Use the best paid promotion channels you can find

- Answer questions on Quora

- Etc.

There are many different ways to promote content, and to know what will work for your business, at the end of the day, you’ll just have to experiment.

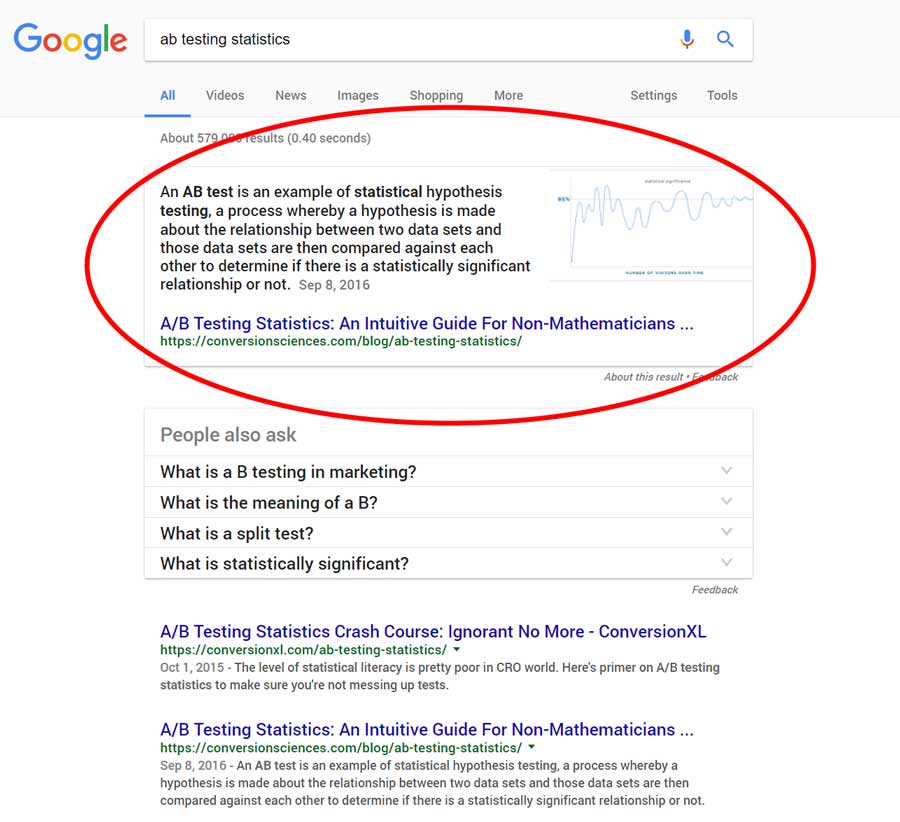

16. Implement Search Engine Optimization

Search engine optimization, mostly known as SEO for short, is a way to optimize a website for search engines and improve your search engine rankings.

The goal is that when people search via Google for phrases that are relevant to your product, your website shows up as quickly as possible.

Unlike most other promotion tactics, getting your site ranked for various keyphrases will result in increasing amounts of traffic over time, or at least for as long as people continue to use search engines.

You get traffic month and month after month, and outside of the expense to rank the site and maintain your ranking, the traffic is free.

By incorporating an SEO strategy, Candoni Wines experienced a 70% improvement in organic search traffic within 6 months. In addition, their site ranks for more than 1000 keywords, and as a byproduct, 20,026 Facebook page likes were added throughout the initial campaign.

By implementing an SEO strategy, this website experienced a 70% improvement in their organic search traffic within 6 months.

17. Participate in Community Events

We live in a predominantly digital world, but promoting your business at physical events is still a great way to grow.

As Digital Vidya discusses, both offline and online marketing are essential:

“As the marketing maxim goes, consumers do not make purchase decisions based on a single ad or message alone. The marketing ‘rule of 7 ‘ states that consumers need to be exposed to a message seven times, on average, before purchase. Buyers gather bits of information from various channels and piece them together in making their decision. Data gathered, from multiple channels, through multiple stages of the buying process, are the building-blocks of sales. Integrated messages that build upon each other, make a compelling case for purchase. Consistency across channels, renders messages more impactful and increases the probability of conversion. As such, integration (of online and offline marketing) is not just about brand synergy – it is about improving ROI.”

Going back to a graphic we looked at earlier, we can see that offline events still make up a sizable percentage of investment for most business decision makers.

This chart shows that global business leaders are still investing in offline events in their marketing strategies.

Participate in those community events where your target audience are. For example, if you are targeting a national audience of retailers, being at a big trade show (see the next point) makes sense. Or to save costs, you could join another company in the same niche at the trade show.

If you depend on local business, local events can be a great way to get new customers, or at least add new people to your email list.

Another idea – if it’s relevant to your business – is to check online event sites for local events.

You just need to figure out what events will be most beneficial to you according to your target audience and goals.

18. Exhibit at Trade Shows

A whopping 99% of marketers say they find unique value from trade shows that they don’t get from other marketing mediums, probably because trade shows pull together a mass group of buyers and sellers in particular industries, who can be considered “hot leads”:

- According to Exhibit Surveys, Inc.,67% of attendees represent a new prospect for exhibiting companies.

- According to CEIR, 81% of tradeshow attendees have buying authority, and 46% of them are in executive or higher management.

Trade shows can be costly to set up, so how do you know if you should take the gamble? Colleen Francis, an influential sales person, recommends participation only if you can make 10x the revenue back within 6 months of the show vs. what it costs you to be there.

Xeikon, a digital printing company, used a trade show as their one main marketing focus for the year, gearing up towards it and following up after it. They experienced these results:

- About 1,000 prospects were identified

- A 14% response rate from email marketing efforts

- 140 new, qualified leads

- 300% return on investment

Find out more about using the sales funnel approach to managing tradeshows.

19. Join A Paid Membership In Your Niche

If you can find some sort of group that requires money to get in AND caters to your target audience, you’ve just struck marketing gold. Joining some sort of paid membership is a perfect, if perhaps a bit sneaky, way to get in front of your target audience.

Paid memberships create an automatic level of trust. The monetary barrier ensures, at least theoretically, that everyone there is committed to being there and on the same page. It’s very easy to promote your products and services in a group you have paid to be in, provided you do so in a subtle way that seems helpful as opposed to spammy.

Examples of this could be local business groups, mastermind groups, paid clubs, course communities, etc.

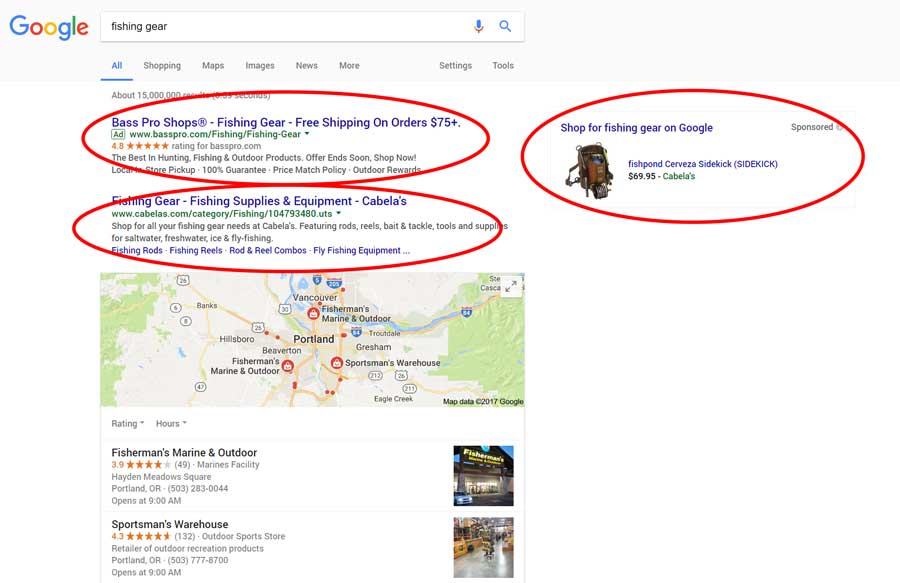

20. Pay For Advertising

Many of the methods provided in this article help to build a customer base over time, but one of the most effective ways to get quick and consistent exposure is to pay for advertising.

Three of the current most popular advertising methods include:

- PPC ads

- Facebook ads

- Television ads

In 2015, the Content Marketing Institute, conducted a survey of 3,714 worldwide marketers, and found that 76% of B2C marketers use paid advertising; 64% rated search engine ads as effective, and 59% reported that they found paid social ads to be effective:

Paid advertising requires some expertise to get right and some experimentation to find the right channel. This is one of the more common promotion activities that business outsource to agencies.

Conclusion: How To Promote Your Business

I hope this article has given you a better feel for how to promote your business. These relatively low investment methods will help you get the ball rolling.

Ultimately, there is no single guaranteed winning strategy for promoting a business. It’s a lot of trial and error, and this list should get you started.